The Chicago CUP: Celebrating six decades of operation and the people behind it

For thirty five years Jack Burgoon, the longstanding assistant of chief operating engineer, has heard plenty of big boilers buzz and shake the old industrial building housing the Chicago central utility plant.

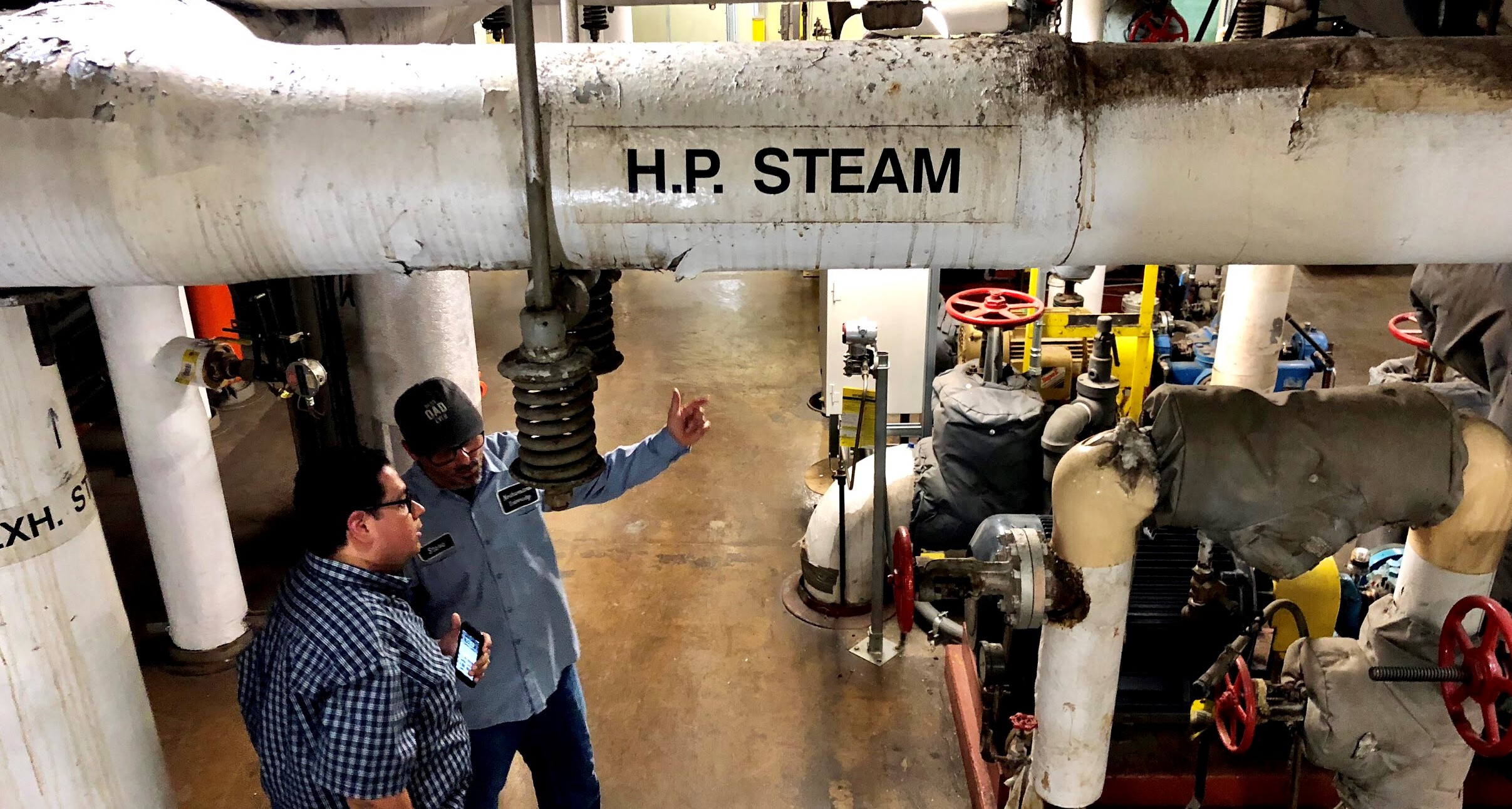

Since 1957, the plant single-handedly has brought steam and water to Northwestern’s Chicago campus and beyond, reaching about thirty buildings at the height of its operation. Today, the plant is still tightly packed with deaerators and economizers and industrial boilers, meant to run a mighty 90 thousand pounds of steam an hour. With four high-pressure boilers, each the size of two stories, the plant has produced decades of efficiency and output.

“They don’t make ‘em like this anymore,” operating engineer Steve Farrell said, pointing to the well-used machines.

Northwestern is in the process of transformation. A decentralization project will replace the few high-pressure boilers operating from a single location with many low-pressure boilers running from buildings across the Chicago campus. With the new boilers running just under 15 pounds of steam an hour, the roles of operating engineers are also changing. The team of seven engineers here will find new homes in maintenance, the engineer shop or the plant in Evanston.

The reason for decentralization is not just about new and improved technology. Upkeeping the old boilers come with stringent EPA regulations, and it is not as cost-effective, according to Keith Barr, the assistant director of Facilities operations in Chicago.

The central plant was “probably the heart and soul of this campus,” Barr said. “Even though we’re not going to be relying on it, the plants that we’re putting in are going to be continuing the legacy.”

Barr is overseeing the decentralization project, the first phase of which is expected to begin Sept. 1. He said the conversation began almost ten years ago, those years spent discussing scope, design and location. Barr added that the project will time out well with the construction of the Simpson-Querrey Biomedical Research Center, which has been designed with an in-house boiler in mind.

“You want to hold it back, but there’s no advancement in that,” Burgoon said. “That’s not a challenge. The challenge is go forward.”

Burgoon gets excited at the mention of a good challenge. In this way, he resembles the very thing he works closest with. Just as an industrial boiler works best in the winter when it is challenged, Burgoon thrives when there is a challenge ahead. A good challenge is what kept him from retiring two years ago, and it will be the very thing he will look forward to in the years ahead.“You want to hold it back, but there’s no advancement in that,” Burgoon said. “That’s not a challenge. The challenge is go forward.”