Full Steam Ahead for Energy Efficiency

Dave Vandas is deep underneath Northwestern's Evanston campus. He is walking through a concrete tunnel tall enough for his six-foot frame to stand in, but not quite wide enough to extend his arms to both sides. Bright white lights along the wall provide enough visibility to see the thick steel pipes running along the tunnel.

As the Chief Maintenance Engineer at Northwestern, Dave knows these pipes and underground tunnels well. They are part of a complex system that carries steam and chilled water from the Central Utility Plant to heat and cool over 200 buildings on the Evanston campus.

Dave and his team are responsible for keeping this system running safely and efficiently. Since 2013, the Engineering Shop has made improvements that have cut energy costs by $2 million dollars annually while improving the safety of the system. It was all thanks to an effort to repair and maintain components known as steam traps.

Every year, Northwestern uses over 1 billion pounds of steam to heat buildings and water, run kitchen equipment, and more. At the Central Utility Plant, located just south of Annenberg Hall, water is heated until it becomes steam. High-pressure steam is then piped through tunnels that run in an elaborate underground system, branching out to provide energy for campus residences, offices, dining halls, and classrooms.

Without properly functioning steam traps, energy is wasted, heat transfer efficiencies are lowered, and conditions can become dangerous. As steam radiates its heat, the steam slowly cools and condenses back into water, called condensate. If condensate isn’t removed from the pipes, it can pool up, blocking steam from traveling into buildings, reducing the efficiency of the system, and creating a hazard. The fast-moving, high-pressure steam can pick up water droplets from the condensate to form a slug projectile called a water hammer. This accelerated slug of non-compressible condensate can slam hard enough to burst through steel pipes and valves.

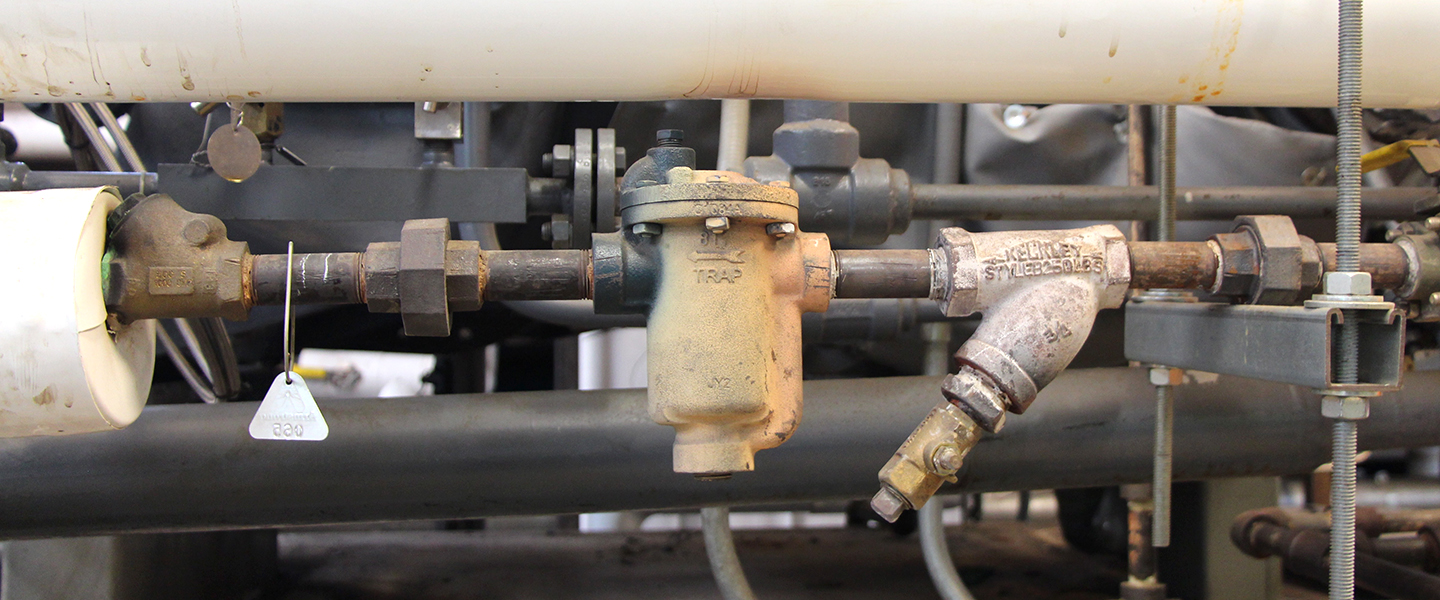

To manage this challenge, the steam distribution system uses a device called a steam trap. A steam trap is an automatic valve that filters out condensate as it collects in pipes. When enough condensate builds up, the trap opens up and releases it into other pipes called the condensate return system. This system of return brings the water back to the main collection tank to be converted into steam again at the boiler.

The Evanston campus has approximately 1851 steam traps. To ensure they are functioning properly and efficiently, each year staff members from the Engineering Shop in Facilities Management spend three weeks straight, eight hours a day, checking on every last one.

The annual steam trap survey began in 2013 when Northwestern began ramping up its energy efficiency efforts. The first survey found that 23 percent of the steam traps on the Evanston campus were failing, allowing leaks of over 100 million pounds of steam. This is equivalent to the annual energy use of 800 average homes. Northwestern’s Engineering Shop took action to correct the problem.

“We replaced or repaired as many of the leaks as we could after that survey,” says Vandas. “Since then, things are much better, and have stayed that way.”

The change was drastic. By 2015, less than 4 percent of steam traps were failing. This year, steam traps are functioning at similar rates. The steam trap work has resulted in a 90 percent decrease in wasted energy since 2013, and savings of almost $2 million each year. With annual surveys keeping things in check, Dave says he expects things to continue going smoothly, creating a smaller environmental footprint and lowering energy costs for Northwestern.