Blog

Leon Forest Lecture, Featuring Professor Farah Jasmine Green

Wilma Tay, One Book Fellow

May 15, 2023

The guest speaker for this year’s Leon Forrest Lecture was author and William B. Ransford Professor of English and Comparative Literature at African American Studies at Columbia University, Professor Farah Jasmine Griffin. As we all sat in the beautiful Vail Chapel on Wednesday for the lecture, Professor Griffin spoke to us about the need to practice an ethics of care. She focussed on American novelist, Toni Morrison and described her as a furious voice for freedom who always practiced an ethics of care.

Professor Griffin spoke about how books like Morrisson’s The Bluest Eye and Ellison’s Invisible Man as well as other Black books were always at the top of ban lists. She shared that most of these books explore many important issues like dimensions of sexuality, racism, and class. She explained how Blacks and canonical societies sometimes sacrificed the Black left and radicalism for the promise of inclusion. She explained that some of the books we are attempting to ban under the pretext of educating and protecting children are simply meant to appease adults, and she claims that novels like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn share important aspects of the history of the American vocabulary.

Furthermore, Professor Griffin impressed upon us to engage and debate works of art and not ban them. She reveals that Morrison saw efforts to ban her work as proof of their power. Professor Grifin described Morrison’s non-fiction as more prophetic and a source of foresight and explains that it appeals to the Black Studies field’s humanistic aspects and builds focus on both local and global political issues. She also shared an excerpt from Morrision’s 1995 Charter Day address at Howard University where she shares the ten steps that lead nations to fascism.

Additionally, Professor Griffin asserts that the true danger of books politicians attempt to ban is the calling out of politicians. She explains that Morrison’s book teaches us to be aware of genealogy, the tools that have been used, the stages we are in, and what we are tolerating. She shares that there are ruins in every book by Morrison and that the ruins remind us that all empires and civilizations end and that those who suffer most love to narrate.

Professor Griffin ended by encouraging us to be vigilant, not comfortable, or complacent. In the ultimate responsibility of aspiring for freedom, we should be unreasonable, not optimistic about the possibility of a humane society, and challenge the tendency of society towards cruelty and censorship. I truly appreciated Professor Griffin’s final remarks and her call to join the struggle for freedom, to help in “building anew on top of the ruin” and to have radical patience for those incapable of imagining a different society or system.

Reading William Still's "Underground Rail Road: Black Bibliography and the History of the Book Now"

Wilma Tay, One Book Fellow

May 15, 2023

Last Tuesday, on Library Workers Day, I attended a captivating discussion led by Cornell University's Derrick R. Spires. The discussion focused on William Still's book "Underground Rail Road: Black Bibliography and the History of the Book Now." Professor Spires, an Associate Professor of Literature in English and accomplished writer, explored the concept of seriality in Black Literary History, emphasizing its three key features: format, narrative mode, and social context. He encouraged us to view Black life as a series of installments, offering valuable insights into pivotal moments and transitions.

Professor Spires highlighted how 19th Century Black authors used pseudonyms to assert their belonging and showcase their creative and informative work. He described Still's "Underground Rail Road" as a fascinating blend of different writing forms, including sketches and biographies. The book serves as a guide, “taking us on a ramble through its pages”.

However, the discussion also touched on some challenges presented by the book. Its publication during the Reconstruction era and its elusive form, which could be interpreted as a memoir, unstructured archive, or fragmented book, made it difficult to classify. Additionally, the frequent additions made by Still right before publication raised questions about the intentional placement of stories. Professor Spires discussed the book's background and its revisions, noting the shifts in management and intent with each edition.

Professor Spires also shed light on Still's market-savviness, and how particularly in the 1870s revisions, where he emphasized groups and families rather than individual narratives, adding names and titles for each person in the book. During the Q&A session, Professor Spires revealed Still's evolving spelling and vocabulary, indicating his growing identification with readers in successive revisions. He shared the story of Still's dedication to serving as a record keeper and preserver of history.

This enlightening discussion provided me with valuable insights into Still's motivations and the various editions of his book. It has inspired me to continue preserving my history and read more critically.

American Studies New Orleans Trip

Vivian Bui, One Book Fellow

May 10, 2023

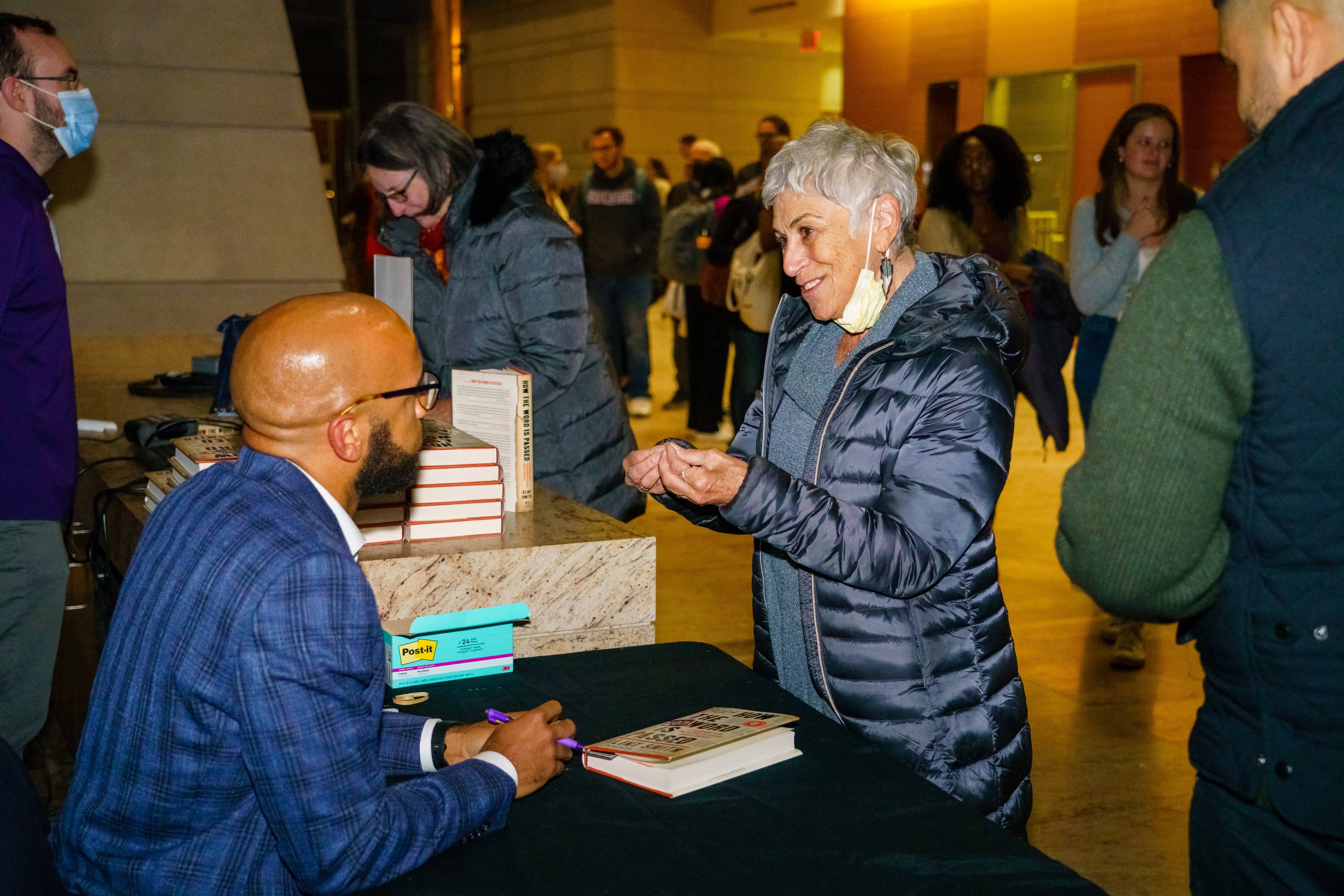

This past spring break, I participated in the American Studies Program trip where we followed Clint Smith’s footsteps and visited New Orleans over spring break! We explored the city and its historical sites, including a few mentioned in Smith's How the Word is Passed.

We visited the Whitney Plantation, which is the only former plantation site in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on slavery. Here, we saw how slavery was an economic necessity for plantation owners. We learned that sugar cane was “king” in Louisiana and that plantation owners saw slavery as a way to acquire free labor. As Smith mentioned in How the Word is Passed and we learned on the tour, Black bodies were used for economic gain, both on the plantation and for medical experiments.

On a Hidden History Walking Tour, we learned more about New Orleans’ history with Leon Walters, the same tour guide Clint Smith mentions in the prologue of How the Word is Passed. We learned how the city changed under French, Spanish, and American colonial rule and the role of the Catholic Church as a major slave trader and an oppressor of women. We also learned about different forms of resistance, such as the creation of the first Black daily newspaper in the United States, the radical New Orleans Tribune, and the struggle to remove the white supremacist monuments today.

We learned more about New Orleans through several other activities as well. We went on a walking tour of the French Quarter with Tulane History Ph.D. candidate and Louisiana native, Derek Woods, where we were introduced to New Orleans’ history of slavery by following historic markers placed by the New Orleans Committee to Erect Markers on the Slave Trade.

We also visited the Laura Plantation, a Creole heritage site. We learned how a slave-holding family had complex relationships within itself, as well as with its enslaved people.

At the Backstreet Museum, we learned about the history behind New Orleans’ famous Mardi Gras celebrations, along with other cultural traditions. We viewed pieces of the world’s most comprehensive collection related to New Orleans’ African American community-based masking and processional traditions, including Mardi Gras Indians, jazz funerals, social aid and pleasure clubs, Baby Dolls, and Skull and Bone gangs.

At the St. Louis Cemetery #1, we visited the grave of Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau and of Homer Plessy, of the landmark Supreme Court segregation decision Plessy v. Ferguson.

We also learned about the history of New Orleans through food! Starting with a dinner at Compère Lapin, which served Caribbean- and European- accented takes on New Orleans flavors, and ending with a crawfish boil, we enjoyed various types of New Orleans cuisine.

This trip allowed me to learn about the history of slavery in New Orleans and question, as Clint Smith did, the histories that are told and passed on.

"Crying in H-Mart" Named as the One Book One Northwestern Selection for 2023-24

Vivian Bui, One Book Fellow

May 10, 2023

As soon as I saw Michelle Zauner’s name, I thought to myself, “Wait… didn’t I see Japanese Breakfast perform 7 years ago?” I thought that if her writing was as great as her music, I should read her book. Crying in H-Mart had been recommended to me at least five times before I saw it listed as an option for the 2023-2024 One Book One Northwestern selection. Like many of my friends, I found myself flipping through tear-stained pages, while laughing out loud at Zauner’s anecdotes. It is compelling, heart-warming, and tragic in all the best ways. It reminded me of my own move away from home and how difficult it can be to leave your parents as “empty-nesters.” While this book represents her Korean American upbringing, many of her experiences are universal. I’m excited to attend her keynote address and for all of the programming (lots of food-related events hopefully) next school year.

"Why Don't White Parents Talk to Their Kids About Race?" Guest Lecture

Izzy Nielsen, One Book Fellow

May 9, 2023

On April 26th, I had the privilege of attending a lecture titled "Why Don't White Parents Talk to Their Children About Race?" by Sylvia Perry, an Associate Professor of Psychology at Northwestern University. The lecture was both informative and eye-opening, and shed light on the impact white families’ discussions surrounding race with their children can have on their children’s biases.

Professor Perry began by exploring why it is important for white parents to facilitate conversations on race. She explained how implicit biases form early in life, and black and white children truly experience different realities — with most black children experiencing discrimination before the age of 8.

Professor Perry continued by laying down the ways white parents approach conversations about race with their children (if they have them at all). Perry established the difference between colorblind messaging and color-conscious messaging and the resulting impact these approaches have on children. Her research highlights the importance of color-conscious conversations in reducing biases. Color-conscious conversations involve acknowledging and discussing the impact of race and racism, teaching white children to recognize their privilege, and value diversity. Professor Perry also emphasized the harmful impact of parents blaming external factors for racism, taking away accountability and not addressing existing children’s biases.

The lecture ended with a Q&A where Professor Perry answered the audience’s questions on everything from approaching the topic of race in the classroom to her best advice for white parents hoping to have productive conversations with their children.

Overall, Professor Perry's lecture was a powerful reminder of the importance of talking openly and honestly about race and racism, especially with children. It highlighted the need for white parents to be actively anti-racist and to take responsibility for educating themselves and their children on these important issues.

"Descendant" Film Hosts Storytelling Masterclass

Izzy Nielsen, One Book Fellow

May 9, 2023

Last Friday, I attended a masterclass with Margaret Brown and Kern Jackson, the creators behind the documentary, Descendants, which screened on April 27th in the Block Museum of Art. The masterclass served as an intimate glimpse into the world of documentary filmmaking and a chance to learn from two accomplished and passionate storytellers.

The class began with a discussion about the ethics of storytelling and who gets to tell whose story. Alongside clips from the film, Margaret and Kern shared stories from working with the subjects of Descendants over the several years of filming. They spoke about the importance of trust and building relationships with the people they were filming. The filmmakers also emphasized the need for sensitivity and respect when dealing with subjects who have experienced trauma and are bravely sharing personal and vulnerable stories from their community.

The conversation also shifted to the creative process. They discussed the editing and scoring process, as well as the adrenaline rush of documentary filmmaking as a whole — knowing you could “find magic” at any moment.

Finally, Margaret and Kern shared the aftermath of the film and what they hope to continue achieving by sharing the story of Descendants. They emphasized the need to shed light on important but little-known stories like Descendants, no matter the challenges.

Overall, the masterclass was a valuable experience that provided insight into the complex and rewarding world of documentary filmmaking. It highlighted the importance of collaboration, ethics, and the responsibility that comes with telling someone else's story. I left feeling inspired and with a new appreciation for the power of film to bring about social change.

Block Museum Screens and Moderates Discussion For "Descendant", a Film About The Discovery of Last Known Slave Ship

Alex Feng, One Book Fellow

April 27, 2023

On Thursday evening, the Block Cinema at Northwestern University was filled with community members eager to attend a screening of the documentary Descendant. Directed by Margaret Brown and co-produced by Kern Jackson, the film follows the lives of the descendants of the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to illegally transport human beings from Africa to America.

The small community of Africatown, located in Alabama, is home to many of these descendants. In the film, they share their personal stories and the community's history, highlighting the resilience and strength of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable oppression. The Clotilda's existence had been a centuries-old open secret, until a team of marine archeologists confirmed the ship's presence.

After the screening, Northwestern History Professor Kate Masur moderated a panel discussion. Masur began the panel discussion by emphasizing the importance of telling and remembering the stories of those whose voices have been silenced.

"We have to think about whose stories are told and remembered, and whose are suppressed. Many of the inequalities in today's world are built on foundations that stretch deep into the past," Masur said.

The film screening and panel discussion served as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for racial justice and the importance of bearing witness to our collective history. Through the power of storytelling, we can work towards a more just and equitable future.

Rethinking Chicago's Historic Monuments: Library Reception

Alex Feng, One Book Fellow

April 17, 2023

Last Wednesday, the One Book Fellows hosted a reception to showcase their Rethinking Chicago's Historic Monuments project at 1 South in Main Library. The project, hosted as a gallery online, is a collection of six monuments in the Chicago area, with each fellow researching one monument.

As is One Book tradition, the One Book Fellows complete a project each year that expands on the themes of the year’s book. This year’s project looked into the history of six local monuments in the Chicago area, exploring the tension and nuances within the history they celebrate. The monuments chosen for the project include the Standing Lincoln Statue in Lincoln Park, the Ulysses S Grant Monument in South Pond, the Benjamin Franklin Monument in Lincoln Park, the Christopher Columbus Statue in Grand Park, the Balbo Monument along the Lakefront Trail, and the George Washington Statue in Washington Park.

Following an introduction that I gave, each fellow presented their research on their chosen monument, with the online gallery providing a platform for visitors to explore the history and significance of each monument. Audience members grabbed food and mingled with one another and the fellows, asking questions about the project and each specific monument. The fellows were happy to share their reflections on the changing meaning of public monuments in Chicago and the importance of rethinking the narratives they represent.

After a year of work, I’m proud that the Rethinking Chicago's Historic Monuments project is something that will sit in the One Book archives as a project that makes an important contribution to the ongoing conversation around public monuments and their place in our communities. On a more personal level, I’m happy that the work we put in throughout the year to research, write about, present, and share the idea from How the Word is Passed that monuments are not static objects but instead dynamic symbols that can be reinterpreted and reimagined over time, resulted in such a polished final product.

How The Word Is Passed: Online Collection Talk

Izzy Nielsen, One Book Fellow

January 26, 2023

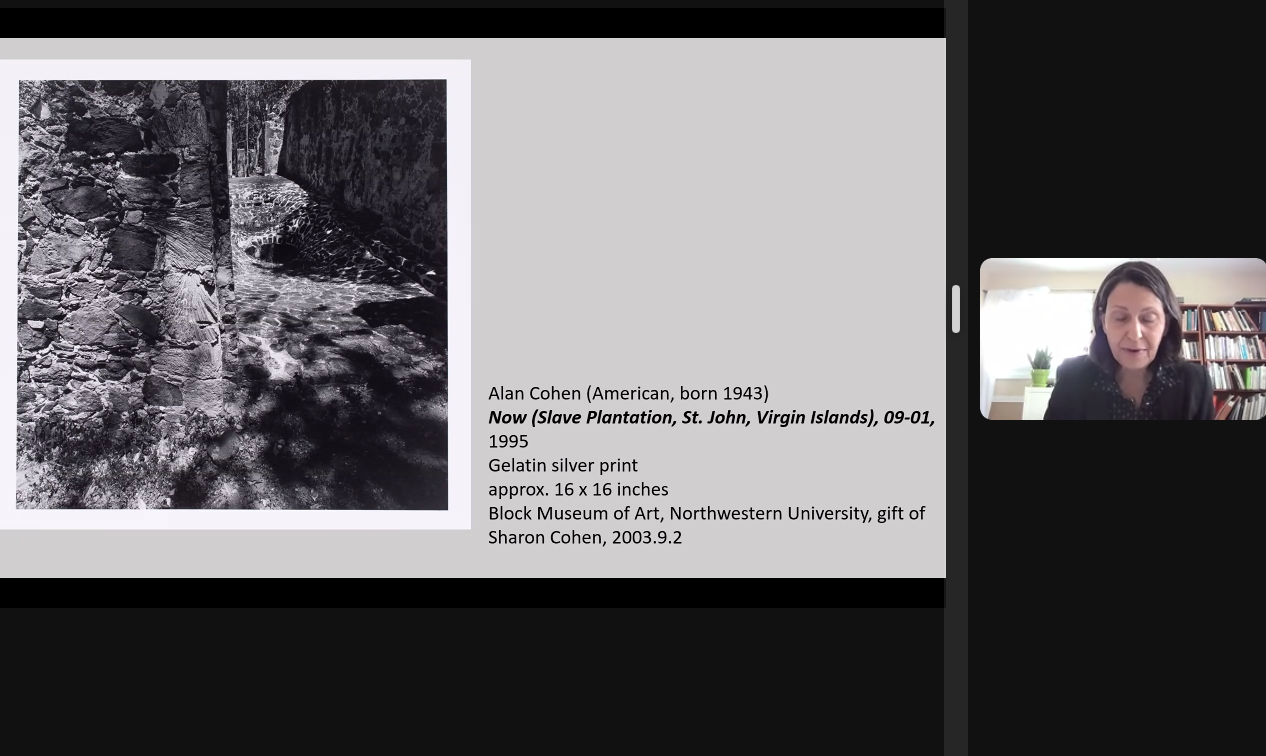

Block Museum Academic Curator Corinne Granof led an online discussion of this year’s Block’s collection this past Thursday, connecting various works of art to this year’s one book selection: Clint Smith’s How The Word Is Passed. The selection of artworks, easily accessible on the Block’s website, explores the themes discussed in How The Word is Passed by highlighting artists making an attempt to reckon with the history of slavery, white supremacy, and racial inequity.

While the complete collection is composed of a variety of artworks from different artists, including photographs, prints, sculpture, and an installation, Granof focused primarily on “Now,” during this talk (a black and white photograph by Alan Cohen depicting a slave plantation in St. John in the Virgin Islands). The piece is part of a larger project by Cohen where he visits various sites of trauma, reminiscent of Clint Smith’s visit to the Whitney Plantation as well as many other historical locations explored in his book. Granof discussed how Cohen’s photograph’s lack of landmarks or symbolic buildings and signs points to a needed reckoning with the often dismissed histories that may unknowingly surround us. She also explored how the composition of the piece spoke to its deeper meaning.

The talk concluded with a Q&A where Granof answered questions about Cohen, the entirety of the Block’s connected collection, and how the Block went about selecting artwork in conversation with How The Word Is Passed. Alan Cohen’s “Now” along with the rest of the connected Block’s collection can be found online and in person at the Block Museum.

Images in Commemorating History: A Visual Storytelling Contest

Lily Pieramici, One Book Fellow

January 27, 2023

Images from the 2022-2023 One Book Northwestern photo contest are now on display in Northwestern University's Main Library in the 1 South Study Space. Students have enjoyed viewing the photos on their way to studying and as a quick study break. The displayed images detail monuments from all over the country. Below the images are small write ups describing the significance of these monuments to the students who photographed them. The images are in response to Clint Smith’s “How the World is Passed,” where Smith analyzes historical monuments. The students' images displayed intend to provide viewers with a new perspective on these monuments. Make sure to stop by and vote for your favorite image using the large QR on the wall.

"How the Word Is Passed": Online Collection Talk

Lily Pieramici, One Book Fellow

January 26, 2023

The Block Museum's curatorial staff spoke about their new collection which presents

ideas and themes related to Clint Smith's, “How The World Is Passed.” The 11 selected pieces

reckon with the history of slavery, social inequity, and white supremacy. Corinne Granof, the

academic curator for the Block Museum, focused on one piece that she thought resonated well

with Smith’s book. She referred to Alan Cohen’s photograph "Now", which depicts a former

slave plantation in St. John, Virgin Islands. Cohen’s picture provides viewers with a fragmented

view of the place, and Granof described it as abstracted in a way that makes it difficult to orient

yourself within the space, or even make out the space. Granof suggested that by giving this

active and tangible view, Cohen and Smith are thinking along very similar lines in their approach

to the past. Both provide a documentation of the site itself without added interpretation, and

Cohen's and Smith’s missions are to present what is true. Both Cohen and Smith suggest that

there is a value in being at the site where events took place. Through Cohen's photos, and

Smith’s writing, they both provide a way of remembering this history to ensure that it can never

be forgotten.

A One Book Field Trip to Chicago's Field Museum

Alex Feng, One Book Fellow

January 25, 2023

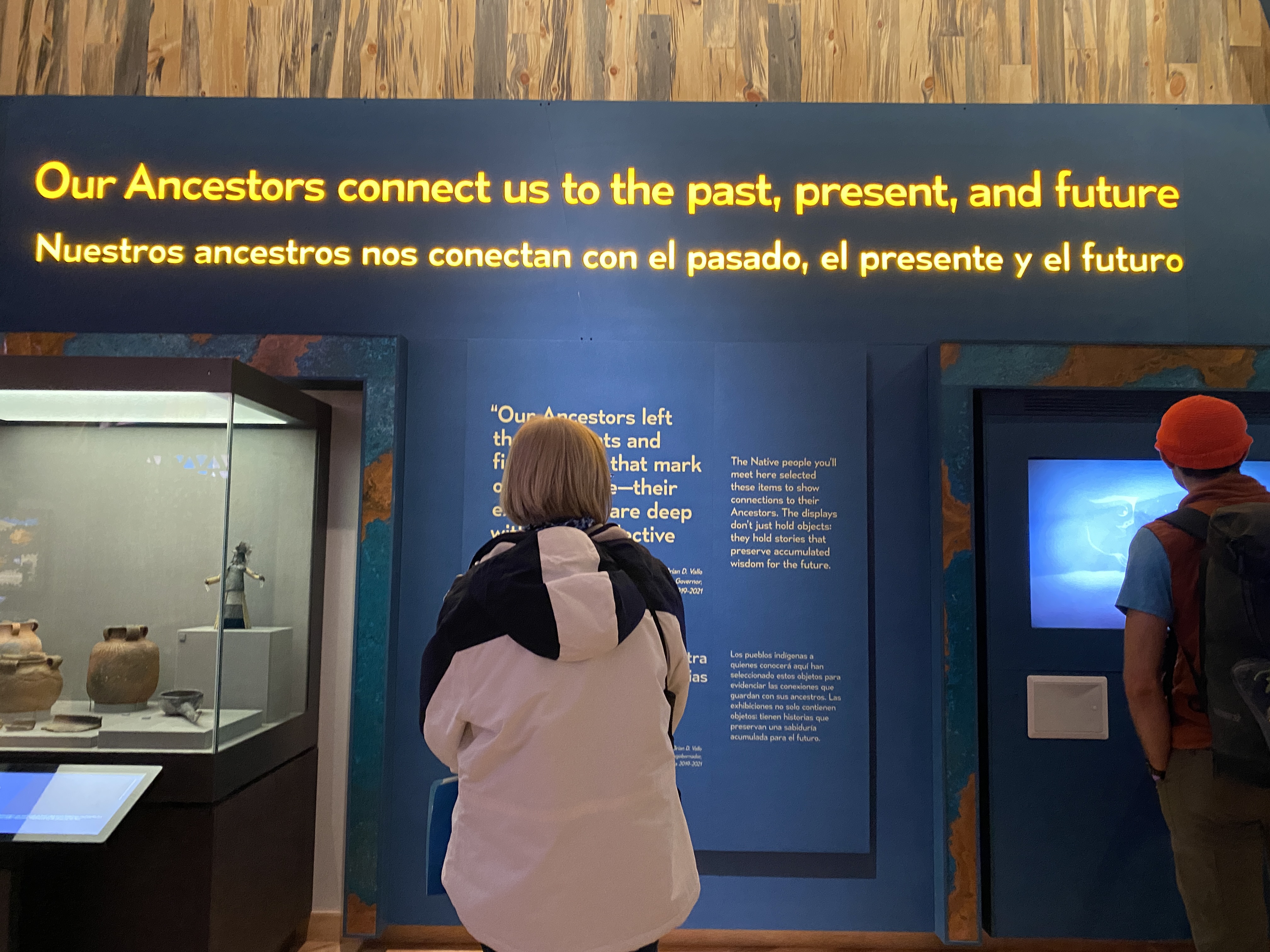

On Saturday, over 40 Northwestern students packed into a school bus for a sponsored field trip to Chicago’s Field Museum to explore its recently added Native Truths: Our Voices Our Stories exhibit.

Upon arrival, students were greeted by Northwestern History Professor Doug Kiel at the entrance of the exhibit. As one of its key advisors, Kiel described the exhibit as a collection of five key truths distilled from the ideas and culture of over 100 tribes. The truths—phrases like “The land shapes who we are”—are emblazoned in orange on walls throughout the exhibit. Surrounding these words are not only artifacts, but also videos, music, interactive games, and photos each telling a story.

Kiel emphasized that the more contemporary elements of Native Truths are a reframing of the “vanishing Indian” narrative. The exhibit’s goals, he said, were to tell a story that connects more presently to Native American culture as vibrant and growing, in ways that are still deeply connected to the past.

“This exhibit could have been a material archive to document the past, but this idea is way wrong,” Kiel said. “This culture isn’t going anywhere. So what do we do? The idea became continuity and change and bringing contemporary artists in and incorporating them. We’re acquiring contemporary native art and situating it alongside a deeper archive of historical material.”

After spending 1.5 hours exploring the exhibit, with Kiel fielding questions about specific displays and curation decisions, the students and Kiel stepped into the museum’s Founder’s Room for lunch. There, Kiel spoke about the museum’s ongoing repatriation efforts to return collection items back to the native communities that wanted them back. His responses to student questions also touched on the lessons that he and other historians had drawn from the museum’s prior, less inclusive, Native American exhibit, which had disrespectfully represented prized objects like buffalo hide paintings. Following lunch, students spent a final hour exploring the museum’s other exhibits before returning to campus.

I loved this field trip, and it was eye opening to hear the parallels between the Field Museum’s exhibits and the monuments described in How the World Is Passed (this year’s One Book’s selection). I came away with a deep appreciation of how alive history really is. At an individual lesson, I realize history is something we engage with everyday with as consumers, participants, and storytellers of it. Learning about the constantly evolving ways that the Field Museum works to improve its relationship with the aliveness of history also affirmed in me the importance of curiosity and respect when engaging with history on my own.

Dittmar Gallery's The Story of Ka Makana o’ka

Vivian Bui, One Book Fellow

December 7, 2022

From October 27 to December 7, 2022, the Northwestern community could visit The Story of Ka Makana o’ka, an exhibit by Trotter Alexander, displayed in the Dittmar Gallery. The exhibit is about a boy from Chicago who experiences a new world when he goes to Hawaii; the name “Ka Makana o’ka” means gifted angel in Hawaiian.

Walking into the exhibit, visitors were greeted with vibrant artwork that addressed topics such as drug use, depression, infatuation, self-hate/love, racial identity, existentialism, and insanity. The exhibit, composed of various mediums, felt like an interactive experience as each piece came to life, appearing to jump off the walls. The emotion that was made visible through bright colors were further emphasized through the expressions of the subjects. The largest piece, featured on a long wall of the Dittmar Gallery, featured a subject who was caught on fire and screaming. On the right of him was a banner of color with other subjects included.

The exhibit reflects Alexander’s first time visiting Hawaii and captures the emotions he felt. The vivid colors and expressions are meant to contrast the typical victim narratives of Black Chicagoans; instead, his exhibit showcases their power and strength.

A Discussion About Housing and Hunger in Evanston

Wilma Tay, One Book Ambassador

November 15, 2022

On Tuesday night, students, faculty, and staff welcomed Susan Murphy, Executive Director of Evanston’s Interfaith Action (IA)—a service organization bridging 41 local faith groups—in leading a conversation about solving housing and hunger challenges in the city. The conversation was the final installment of Northwestern Leadership Development & Community Engagement’s and Religious & Spiritual Life’s jointly created fall Civil Love Program.

The event began with a gratitude share-out—everyone sharing what they were thankful for—followed by Murphy’s introduction of her organization. IA, Murphy shared, was founded in the 1970s and provides social services to Evanston community members. The homeless support initiative began 15 years ago when a member church began providing food and shelter for Evanstonians between 7 PM and 11 AM when the temperature went subzero, Murphy said. Now, nine faith communities offer homeless sheltering from October to May. IA’s hunger initiative operates soup kitchens at least once a day, Murphy said. Usually, 50-90 families will show up per meal, from all different backgrounds—some homeless, others simply unable to afford food. Supporting this program are the monthly blanket and produce distributions at the Robert Crown Center, called Producemobile. At these events, which are partnerships with the Greater Chicago Food Depository, IA volunteers can hand out food, blankets, and fresh produce to up to 300 families, Murphy said. SNAPGap, another IA program, was also recently launched to distribute toilet paper and laundry detergent, items not covered by SNAP.

Murphy concluded by encouraging Northwestern students to get involved through volunteering, and cited her faith as an influence on her work. Responding to a question about how cash-strapped individuals might support anti-homelessness initiatives, Murphy suggested donating items like socks, gloves, chapstick, and earpieces (to deal with noise in crowded shelters), and volunteering at item distribution events. On a personal level, Murphy said working in IA gave her far more empathy regarding homelessness and hunger: homeless folks are simply people who happen to be homeless, and they are as human, and just as deserving of courtesy and respect, as everyone else, she said. IA is expanding its programs, Murphy added, and everyday inspiration for her work come from small gestures, like her children and grandchildren eagerly coming out to help.

IA’s work was an inspiration to me, and I really appreciated the reminder about the need to always acknowledge the humanity of everyone around us.

In Pursuit of Revolutionary Love

Wilma Tay, One Book Ambassador

November 10, 2022

On Friday, philosopher, author, and Williams College professor Joy James joined us at Northwestern University’s Guild Lounge to discuss revolutionary love.

James spoke to us about “captive maternals” — individuals tied to the state's violence through their non-transferable agency such that they have to care for another — and she gave the example of how the incarcerated take care of each other despite the hardships each of them face. The project, which began in 2016, was inspired by her observation of parents trying to get services for their families. Through this, James explained the concept of "captivity through family,” and the stages of the captive parent: Conflicted Parent, Protestant, Progress maker, and Rebel.

James also encouraged us to reflect on one of James Baldwin’s famous statements: that “we are more integrated than we want to.” By examining the contradictions between the legalism that protects us, and aspects of betrayal wrapped in it, she explained how aspects of the Constitution that appear to confer rights and freedoms can actually be trojan horses. James further explained the ways in which the United States qualifies as an empire, and how the system prevents individuals from reclaiming their stolen wombs and identity. There’s a need for more accountability, especially regarding our involvement with other nations, she explained. At a community level, she also talked about how culture and race have been used as props, and how the narratives of culture have been flipped against us.

James concluded by urging us to think about what it would mean to acknowledge decorum, but still move beyond it. She also reminded us about the need for an emotional register, and she invited us to think about what kind of intellectuals we can become as guerrilla theorists.

This talk was followed by a reception where attendees continued to discuss some of the issues raised in the talk.

I sincerely enjoyed this event, as well as the call to think more critically about our identities and how to be more accountable.

Deering Library's New "Freedom for Everyone" Exhibit Explores Slavery and Abolition

Izzy Nielsen, One Book Fellow

November 3, 2022

This Wednesday, Northwestern History PhD student Marquis Taylor presented “Freedom for Everyone: Slavery & Abolition in 19th Century America”, an exhibit that he researched and curated for Northwestern Libraries, which is now on view in the Deering Library lobby. The exhibit, a collection of documents highlighting the work of 19th century abolitionists, was inspired by Northwestern’s first observance of Juneteenth.

Taylor, along with McCormick Library staff Jill Waycie and Charla Wilson, started the project as part of Northwestern library’s efforts to revise the outdated and often harmful language used to describe historical collections. Work began by curating a collection of Frederick Douglass-related materials and renaming the previously titled “African American Documents Collection” to the “Slavery, Enslaved Persons, and Free Blacks in the Americas Collection.” Taylor’s final exhibit is made up of historical documents from these two collections, including items like preserved letters written by Helen Douglass (Frederick Douglass’s second wife), to original copies of abolitionist autobiographies, to historical copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The exhibit’s various themes are framed by its title “Freedom for Everyone”, which are words taken from activist and teacher Opal Lee who fought tirelessly for Juneteenth’s place as a federally recognized holiday. Juneteenth represents “freedom for everyone” and a necessary moment of reflection for all of America, Taylor said, in many of the same ways this exhibit is intended to be.

After giving visitors some time to explore the collection, Taylor hosted a Q&A where attendees asked questions about his work and research process. The goal for the exhibit, Taylor explained, was to help people “understand slavery as something more complex” and show how the North and South in the 19th century were not as binary as one might have been taught; they all “lived in a slave society.”

The physical exhibit will remain behind glass in the Deering Lobby until the end of fall quarter. In the meantime, Taylor and the library staff will continue updating the digitized version of the exhibit on the library’s website, their suggested relevant reading list, and an extensive spreadsheet compiling enslaved people’s histories.

Understanding the Historic Evanston Black Community

Diana Deng, One Book Ambassador

October 31, 2022

Community members had a chance to learn about the history of Black Evanston on Saturday through a bus tour jointly organized by One Book One Northwestern, the Evanston Community Foundation, and the Shorefront Legacy Center (SLC).

The tour started on the lakefront and moved west towards Skokie. At various stops, Dino Robinson, the founder of SLC, pointed out locations that were once Black churches, schools, and Black-owned businesses. These locations were sites of a violent racial history that had remained buried until recent years, Robinson said. As we learned on the tour, the story of each site’s destruction in the early twentieth-century was wrapped in threads of city redlining, Jim Crow policies, and racist housing standards. All of which forced Black residents who were unable to afford city-mandated home improvements to sell their homes and move out of the region.

One of the first stops was the Masonic temple on Emerson street, where Robinson pointed out spots that many in the Black community had stopped at to socialize, ask for help, and receive vocational training. It was incredible how despite segregation, Black businesses and cultural traditions not only developed but thrived, Robinson said.

Upon arriving at Evanston’s western border with Skokie, Robinson explained that land around the city’s canal had been dug-up in the 20th century as a way to physically isolate and demobilize black populations. The impact on Black communities from actions like these was further exacerbated by legal decrees like the Land Clear Ordinance.

Our tour ended in the library of the SLC. There, Robinson showed us the SLC's 25 years of history as a museum and research center dedicated to recording, studying and preserving the experiences of African Americans living in the North Shore communities of Chicago. This showcase made me particularly grateful; if not for the efforts of organizations like the SLC, the chance to learn about this history would have been lost forever!

The one-hour tour of Black Evanston blew my mind. In particular, I was struck by how the buildings I see everyday belie such a tragic history of a violently uprooted community. The tour left every one of us thinking about how a present appearance of peace and prosperity might have subtly influenced us to turn a blind over difficult histories—and our responsibility to reckon with the truth lying beneath our communities as we know them.

Author Clint Smith in Conversation with History Professor Leslie Harris

See a full gallery of the photos from the October 18 event here.

Vivian Bui, One Book Fellow

October 25, 2022

Clint Smith joined the Northwestern community in Galvin Hall last Tuesday to share the inspirations, hopes, and journey around his recent book, How the Word is Passed. In discussion with Professor Leslie Harris, Smith began by introducing how he wished that his education had given him a more holistic understanding of slavery. The experience of slavery, and its legacy, is more than just extraordinary outlier biographies of folks like Frederick Douglass and Rosa Parks and stodgy textbook chapters on the various jobs of plantation slaves, Smith said. It’s the hopes, dreams, relationships, and everyday experiences of what it means to try and live life as a fully realized person in an institution that oppresses that person’s very existence.

Smith said that this more complete, situated narrative is what he hopes his readers will take away from the visits to various historical sites that he documents in his book. Challenging how these narratives are told in the monuments and street names that we pass by everyday is important to understand how our current institutions, and ourselves as individuals, fit into the stories of people that happened centuries ago.

As much as the book is a call-to-action to think critically about the way histories around us are preserved, it’s also an intellectual toolkit for individuals like his own young self to understand the context of their present lived experiences, Smith said. It’s hard to work through difficult pasts especially when the stories in question aren’t part of popular discourse and education, Smith acknowledged. But that makes it all the more important for each one of us to stay vigilant in interrogating the answers we’re given, and to reach constantly for better ones.

Dittmar Gallery Dinner: A Night of Remembering Illinois's Early Black History

Izzy Nielsen, One Book Fellow

October 24, 2022

Northwestern History Professor Kate Masur’s lively dinner discussion on Illinois’s early Black history filled the Dittmar Gallery with a mix of students, faculty, and alumni on Thursday night. The evening centered around stories of Black Illinois residents told in the online gallery Black Organizing in Pre-Civil War Illinois: Creating Community, Demanding Justice, a Northwestern History Department research project spanning over two years.

Masur set the historical backdrop with a lecture highlighting Illinois’s repressive legal history and the subsequent networks of Black residents that formed to organize against it. This history, she explained, led to the organization of some of Illinois’s first statewide conventions. Following the lecture was a buffet dinner where undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, alumni, and local residents engaged in discussion over food at each table. The evening concluded with a share-out. Each table summarized key takeaways from their conversations, expanding on Masur’s initial lecture with a range of personal experiences and perspectives.

Overall, I thought it was a very educational and greatly eye-opening evening!

Ready to Rethink

Leslie M. Harris, Professor, History; Judd A. and Marjorie Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences

2022-23 One Book One Northwestern faculty chair

October 3, 2022

When I first arrived at Northwestern as a faculty member in Fall 2016, I would not have thought there was a need to rename streets or remove statues. As someone who had grown up in New Orleans, Louisiana, and taught for 21 years at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, I had been surrounded by statues and street names celebrating pro-slavery white southerners: Robert E. Lee Circle near the Museum of the Confederacy, and Jefferson Davis Parkway, in New Orleans. Confederate and East Confederate Avenue in Atlanta, as well as Memorial Drive leading to the Confederate Memorial in Stone Mountain, Georgia. In Evanston and Chicago, I was stunned by the repetition of Abraham Lincoln’s name: on schools, streets, and not least the “Land of Lincoln” phrase on my car’s new license plate. It was a relief to see the widespread celebration of someone I associated, even imperfectly, with the emancipation of my enslaved ancestors.

But I had to learn to look with new eyes, and to place what seemed initially positive in new contexts. I arrived at Northwestern amid the university’s reckoning with its relationship to Native American history. Northwestern had just completed an important and at times controversial and contentious effort to revisit the role of one of its founders, John Evans, in the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, an event in which the U.S. Army murdered 200 mostly unarmed Cheyenne and Arapahoe men, women and children who believed they were under the protection of the U.S. government. Evans was governor of the Colorado Territory when the massacre occurred and bore responsibility for it.

Learning about the historical context of my new home university reminded me of some parts of my past I had previously been less engaged with. As I learned more about the history of relationships between the United States and numerous Native American nations during the Civil War, I also learned that President Abraham Lincoln had presided over the largest public execution in U.S. history: the hanging of 38 Dakota Sioux men, just one week before he signed the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. In New Orleans and Atlanta, there were streets named for Native peoples from whom land had been stolen decades before, and who had been forced onto reservations. Many Black and white southerners like to claim Cherokee ancestry, but in reality most of us have benefited from the land theft, relocation and murder of former inhabitants who we now know only via street and place names.

As an historian of the United States, I also confronted again the fact that the development of “freedom” for some was often rooted in the oppression of others. Historians have written for decades of the central contradiction of U.S. history: The land and wealth that led to the possibility of the “Founding Fathers” envisioning independence from Great Britain and democracy for themselves was made possible by the enslavement of people of African descent and the theft of land from Native peoples.

What happens when we confront these stark realities? What do we do with the knowledge that our own wealth—intellectual, political, economic, and more—occurred because of enormous losses, if not crimes, inflicted upon others? What is our responsibility to the legacies of these difficult histories?

Clint Smith’s book takes us one small step in the right direction by inviting us to join him in an honest engagement with our complex histories. How the Word is Passed gives specific examples of difficult histories, but it also provides examples of how to engage thoughtfully with those histories, and with those who might disagree with us about their meaning. Whether in a classroom, in an art installation, at a museum, or on a walking tour, we have the ability—indeed the responsibility—to seek honest engagement with “hard histories.” The ethical questions we face in our lives don’t necessarily become easier, but we become more adept at recognizing their importance, and at doing our part to work towards greater justice for all in our own time.

--with thanks to Kate Masur and Nancy Cunniff for their helpful edits.

Exploring Our History and Our World in Community—and In Person!

Leslie M. Harris, Professor, History; Judd A. and Marjorie Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences

2022-23 One Book One Northwestern faculty chair

September 12, 2022

We enter a new academic year at Northwestern with a renewed commitment to in-person learning, which includes learning how to live, learn and work together in community. This year’s book selection and programming for One Book One Northwestern is an opportunity to take a closer look at the various ways that different groups of people encounter and understand history in our Northwestern community, the Evanston and Chicago area, our nation and our world.

In How the Word is Passed, Clint Smith charts his personal journey to historic sites of enslavement, imprisonment and war in the U.S. and West Africa. In doing so, he engages with experts at these sites and with other visitors, and he examines books and other materials to come to a deeper understanding of the role of slavery and race in our common history. His goal is to understand what we can learn from different historic sites, scholars, and each other about these complex histories. Smith also models how to have conversations on difficult topics with people with whom you may disagree. Finally, Smith champions, I think, the possibility that learning can happen in any situation—not just in the classroom, and not just in books. We can engage physical spaces and each other to reach a deeper understanding of the world around us.

There’s probably been no better time to encounter How the Word is Passed than today. The United States has been roiled by events that have led to deep questioning of the meaning of race, the history of slavery, and the fairness of our justice system. Ongoing controversies over teaching “Critical Race Theory” and the New York Times’ “1619 Project” in K-12 schools are just the latest a series of conflicts over the meaning of freedom and justice in our world. In fact, we could write the history of the United States as a long series of battles about the meaning of freedom: What is it? Should everyone have the same freedoms? Where does my and your freedom begin and end?

Specific, recent events have turned our attention to the history of race and slavery. In 2015, the June murder of nine African American worshippers in Charleston, South Carolina’s historic African Methodist Episcopal Church by a white supremacist led the state of South Carolina to remove from statehouse grounds the Confederate battle flag, a symbol of the pro-slavery states who seceded from the United States and sparked the Civil War. White southerners had brought the flag into prominence in the South in the 1950s, making it a symbol of their opposition to the Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education, and to other federal policies designed to end segregation and protect Black Americans’ right to vote. Many southern communities also had statues, street names, and other markers that honored the Confederacy.

But when South Carolina lowered its Confederate flag, other states, cities, schools, and institutions began to reconsider symbols of the Confederacy that remained part of their landscapes and sought to remove them. In Fall 2015, students at schools from Yale to the University of North Carolina and beyond urged that buildings named for leaders of the Confederacy be renamed and that imagery of the Confederacy—flags, statues, and other symbols—be removed from campuses. The inquiry extended beyond the Confederacy as people in communities across the country questioned monuments honoring slaveowners of earlier generations, segregationists, and people who had participated in the dispossession and murder of Native peoples—including at Northwestern. Communities asked that street and school names be changed and statues removed. These efforts continue down to today, as communities decide what to preserve, what to remove, and what to commemorate today and in the future.

Some have argued that removing statues and other markers is erasing history. In How the Word is Passed, Smith visits locations—Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and Blandford Cemetery in Virginia; New Orleans and the Whitney Plantation in Virginia, to name just a few—where these histories have been preserved and reinterpreted, and where they have not been. As Smith exemplifies in his journeys, we all have the power to witness and interrogate the history presented to us in monuments, landscapes, and museums—and yes, even in classrooms. But as Smith also makes clear, witnessing and interrogating also carries the responsibility of constructive engagement, civic exchange—and perhaps, even doing your own research!

--Thank you to Kate Masur and Nancy Cunniff.