Heart and Soul

Related Articles

Online Exclusive:

A Friendly Mission

Sean Hargadon is senior editor of Northwestern magazine.

Chaplain Timothy Stevens to give us a virtual tour of the stained-glass windows, which he likened to a Highlights magazine.

Check out this video on Alice Millar Chapel, produced by Sedgwick Productions for the Big Ten Network.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Ever wonder about those strange designations we use throughout Northwestern to identify alumni of the various schools of the University? See the complete list.

Find Us on Social Media

More than a house of prayer, Alice Millar Chapel celebrates a half-century as the University’s spiritual center.

Ambika Kasbekar embarked on her spiritual journey without so much as a map. Growing up in Hyderabad, India, she never really had a faith life. Her parents didn’t practice any particular religion, and they never gave a straight answer about what they believed.

But during her junior year at Northwestern, when she served as the community assistant for the Office of Religious Life’s Interfaith Hall, Kasbekar ventured to the Alice Millar Chapel for Sunday service, eager to learn about interfaith life and understand the religious backgrounds of the hall’s residents.

“When I first attended a chapel service at Alice Millar, I did not identify with many of the customs and passages from Scripture,” Kasbekar says. “But something kept bringing me back. I liked that Alice Millar embraced people from other faiths and made me feel at home even though I wasn’t Christian.”

During her senior year Kasbekar opted to live again at Interfaith Hall, a living and learning community, now located on the top floor of 1835 Hinman, and she became a regular at Alice Millar’s nondenominational Sunday service.

“When I went to the Alice Millar chapel services, it seemed warm and welcoming,” says Kasbekar (WCAS10), who is studying for a master’s degree in mental health counseling at Minnesota State University in Mankato. “I could go there for my spiritual needs.”

The chapel, which turns 50 this academic year, has long been a welcoming place of worship for those who are seeking spirituality. It’s also a house of inspiration to those who embrace social justice, civil rights and the beauty of interfaith life.

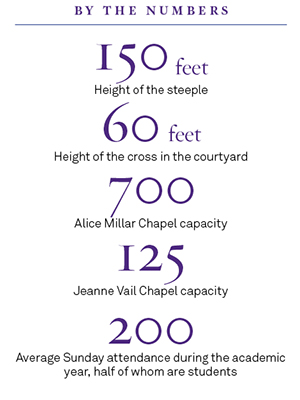

Completed in September 1963, the Alice S. Millar Chapel and Religious Center is named for the mother of businessman and philanthropist Foster G. McGaw, founder of the American Hospital Supply Corp. and a longtime University trustee. He and his wife, Mary Wettling Vail McGaw (WCAS23, H73), funded construction of the religious center, which also includes the Jeanne Vail Meditation Chapel — named for Mary McGaw’s daughter, who died of polio in 1949 — and Parkes Hall Religious Center, home to the chaplain’s office, classrooms and meeting spaces.

Photo by Michael Goss

“A large bustling university, crammed full of competing interests for the student’s time and attention, should have one facility which is apart from all others, a place where the soul may find quiet and repose,” Foster McGaw told the crowd at the dedication on Nov. 17, 1963.

One week later the chapel pews were filled again — this time with mourners.

“When President Kennedy was assassinated and people came pouring in,” says longtime chapel secretary Marge Bradford, “I remember thinking, where would everyone have gone if this had been last year? There would have been no chapel on campus.

“That was the first inkling of what this place would become.”

When the chapel opened in 1963, “it might as well have still been the ’50s in a sense,” says Bradford, who joined the staff three months before the chapel opened. At the time the chapel had a board of ushers, and fraternities and sororities donated flowers for the Sunday morning services.

In a few short years, however, society and the campus changed, and the chapel with it, as Alice Millar became a center for social justice. Ralph Dunlop, a United Methodist minister who served as the first University chaplain at Alice Millar and oversaw the construction of the chapel, went to Selma, Ala., in 1965 with a Chicago-area committee of clergymen in support of the freedom marches. The following fall, Fannie Lou Hamer, a famed civil rights leader who had been jailed and beaten in Mississippi, preached from the pulpit at Alice Millar Chapel.

In a few short years, however, society and the campus changed, and the chapel with it, as Alice Millar became a center for social justice. Ralph Dunlop, a United Methodist minister who served as the first University chaplain at Alice Millar and oversaw the construction of the chapel, went to Selma, Ala., in 1965 with a Chicago-area committee of clergymen in support of the freedom marches. The following fall, Fannie Lou Hamer, a famed civil rights leader who had been jailed and beaten in Mississippi, preached from the pulpit at Alice Millar Chapel.

Later the chapel hosted peace vigils in response to the Vietnam War. In the mid-1970s the chapel housed the Northwestern Amnesty Center, an organization that raised awareness about the thousands of men who had been imprisoned or fled the country after refusing to serve in Vietnam.

In the 1980s the chapel hosted protests against U.S. intervention in Grenada and rallies for peace in Guatemala. Former chaplain Jim Avery (WCAS71) advocated University divestment from sources of income related to apartheid in South Africa.

In the late ’80s the chapel staff worked to raise awareness about the AIDS epidemic, and Alice Millar hosted frank discussions about safe sex and offered memorial services for those who died of AIDS. When a group of gay students wanted to start a coffeehouse on campus, Avery opened up a room in Parkes Hall on Friday nights.

“The chapel has always been a safe place for people to go,” says Bradford.

This past summer, Andrew Hotz (C02), a native Chicagoan, called University Chaplain Timothy Stevens (G82, 90) with a request. Hotz, who was raised Catholic, and his partner, Kevin, who is Jewish, had adopted a baby boy, Leo.

“We wanted to have some sort of ceremony, or two ceremonies in this case, that were representative of our backgrounds,” says Hotz, who lived at Allison Hall, across the street from Alice Millar, during his freshman and sophomore years. They had a bris in New York City, where they live, and then Hotz called Stevens to inquire about an infant dedication.

Hotz’s Chicago-area family attended, including his best friend from Northwestern — now his brother’s wife — Emily Africano Hotz (WCAS03).

“It was very small, just family,” Stevens recalls of the ceremony. “The grandfather was pushing the stroller in, and I said, ‘Oh my goodness, what a beautiful child.’ And the grandfather says, ‘Yes, and he has two wonderful dads.’ And I thought, ‘Wow, how far we’ve come.’

“We’ve quietly moved ahead with things like that and without being confrontational have just been there for people.”

And Stevens has brought that mission overseas, as well, taking groups of students from Alice Millar Chapel and University Christian Ministry on an annual spring break Friendship Mission. Destinations have included communities in Cuba, El Salvador, Haiti and Russia. The students do some volunteer work but spend most of their time meeting with local nonprofits, visiting schools and learning about the realities of life in that particular place.

“We want the students to actually interact with the people who are hosting the group,” Stevens says. “The idea is that we’re going to a place not to evangelize but to establish relationships with people in a different part of the world in a different social reality. If a conversion takes place, we’re the ones who get converted.”

(Read more on the Alice Millar Chapel Friendship Missions.)

The chapel’s social justice mission is built into its very structure. Among the Alice Millar Chapel’s magnificent stained-glass windows, one focuses on the races of humanity, with an image of five hands of different colors interlaced in an appeal for harmony. The Belgian-born artist, Benoît Gilsoul, and fabricator, Henry Willet, created the image even before Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in August 1963.

“The civil rights movement was going on, with a lot of turmoil in our cities and on our campuses,” Stevens says. “And here’s this image of racial harmony.

“That window is still there. It celebrates racial harmony but also challenges us. In some ways that’s what the chapel has been about, being out in front.”

But the windows were perhaps too “out in front,” too forward-looking for the chaplain-appointed faculty committee charged with selecting the design in the early 1960s.

When Willet, of Philadelphia-based Willet Studios (now Willet Hauser Architectural Glass), first rolled out the plans, the committee was appalled.

“They thought the design was too complicated and just strange. They had never seen anything like it,” Stevens says. Longtime Kellogg School of Management professor Gene Lavengood, head of the committee, led the opposition, which only relented when Northwestern President J. Roscoe Miller (FSM30, GFSM31) stepped in.

When the windows were finally installed shortly after the chapel opened, the skeptics were quickly converted, Stevens says. “When I first heard Professor Lavengood tell this story, he looked around and said, ‘I was wrong. These windows are amazing. You have to live with them for a while, and then you come to really appreciate what they’re trying to do.’

“I love that story,” Stevens adds, “number one because a faculty member said, ‘I was wrong.’ But also there’s a lot of truth to that. These are challenging windows that really ask a lot of people to interpret.”

The chancel window at the front of the chapel — the largest in the country when it was installed — tells the story of Christian biblical theology. (When the chapel was built, the University was still connected with the United Methodist Church, a relationship that officially ended in 1974.) The 10 side windows represent academic endeavors of the University — communication, law, literature, the arts, commerce and industry, politics, science and medicine. Stevens’ favorite window shows an angel supporting an astronaut.

“When I was a kid, there was always a ‘Hidden Picture’ in Highlights magazine,” the chaplain says. “There would be a toothbrush or a comb hidden in a tree. I think these windows are kind of like that. It’s a process of discovery. That complements my understanding of what it means to be spiritual. It’s not that everything is just handed to you. You have to really think about it and search and try to put things together and make sense of it all.

“That process of discovery is also a great metaphor for the University, where the purpose is to grapple with issues, find patterns of meaning and figure out what that all means for our lives.”

Today’s students are the children of 1960s- and ’70s-born parents who perhaps moved away from a life of faith or never attended church services at all. A 2012 Pew Research Center study found that 35 percent of Americans between 18 and 29 are religiously unaffiliated. At Northwestern nearly 33 percent of students in the class of 2015 identified as having no religion when they arrived on campus in 2011.

“The Pew Foundation calls them the ‘nones,’ people who may believe in God but don’t identify with any religious denomination or tradition,” Stevens says. “I want the chaplain’s office to be in a position to have a conversation with those folks and say, ‘OK, church or synagogue or mosque or whatever isn’t necessarily doing it for you. But what would?’ ”

The quest to reach the religiously unaffiliated spills over into the chapel’s interfaith programming, which began in the mid-1990s and intensified after 9/11. The chaplain’s office coordinates nondenominational Christian services on Sunday mornings while also nurturing a diverse and robust religious life that includes many different traditions.

For example, Parkes Hall is home to the Muslim-cultural Student Association’s Jumah prayers on Friday afternoons. The Hindu Student Association gathers there for Diwali, the five-day Hindu festival of lights. The Bhakti Yoga Society and the Zen Club meet at the religious center.

The Northwestern University Interfaith Initiative, a sustained dialogue group, breaks bread every Monday at Parkes Hall, where they discuss issues such as eschatology or women’s rights in different religious traditions.

“We have students from all walks of life,” says associate chaplain Tahera Ahmad, from atheists to students who are devout in their faith. “It’s great that they’ve found a way to come together and have respectful, open and meaningful dialogue.”

Ahmad also advises Interfaith Hall, which is home to 20 students often from a variety of religious and faith backgrounds, as well as atheists and agnostics.

The Office of Religious Life, which includes Ahmad and fellow associate chaplain Jackie Marquez, works closely with the leaders of more than 40 religious student groups, which represent Baha’i, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish and Muslim faiths, as well as a secular humanist group. There are also five unaffiliated religious centers.

“Northwestern is a secular university, not affiliated with any particular religion,” says Northwestern President Morton Schapiro. “But that shouldn’t mean that religion and spirituality aren’t welcome on campus. In fact what it means is that all religions are welcomed equally. At Northwestern we have people with many different backgrounds and beliefs, which is one of the reasons Northwestern is such an interesting place.”

The Alice Millar Chapel, “a space in which music lives beautifully,” says music director Stephen Alltop, is home to the Alice Millar Chapel Choir. The 40- to 50-member interfaith ensemble is made up of graduate and undergraduate music majors and general campus students. “Some are churchy people,” Alltop says. “Some have never been a part of any formal worship experience.

Photo by Jill Brazel

“The chapel itself and the choir are open and large enough for anyone who wants to be a part of them.”

The chapel’s namesake, Alice Millar, was a noted musician who once performed for Queen Victoria. So it’s fitting to celebrate her birthday (Jan. 28, 1859) with the grand Alice Millar Birthday Concert, held annually in late winter since 1978.

This year the concert will feature a new work commissioned for the chapel’s golden anniversary. Joseph Schwantner (GBSM66, 68), a distinguished alumnus and one of the most successful contemporary American composers, penned a five-movement piece called “Chapel Music” that will premiere at the concert on Feb. 9.

It will be one of several events throughout this academic year to celebrate the University’s spiritual center.

“I used to say the chapel is the largest invisible building on campus,” Stevens observes, “because people would walk in, and they’d go, ‘Is this part of Northwestern?’

“ ‘Yeah, it is. This is your place!’

“Even for people who are not religious, the chapel is a place that means something. This is a place where people gather at important moments. It’s a place where people can come together and get a perspective, a spiritual perspective, on things. Our ultimate goal is to be a big house where a lot of people can come and find something that’s meaningful to them.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email