Zach Brock Almost Never Was

Related Articles

Neil Tesser ’73 is a jazz critic who has written on and broadcast jazz in Chicago for four decades. He has produced liner notes for more than 350 albums and won a Grammy last year for Best Album Notes for his work on Concord Records’ Afro Blue Impressions.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Ever wonder about those strange designations we use throughout Northwestern to identify alumni of the various schools of the University? See the complete list.

Find Us on Social Media

Violinist Zach Brock has fiddled his way to the top of the music world with his masterful blend of classical and jazz music — despite a life-threatening accident while a student.

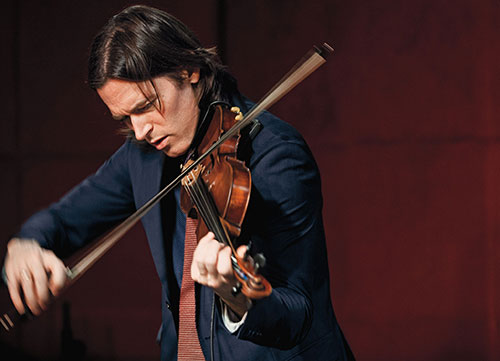

It’s an autumn Friday night at the Green Mill, Chicago’s liveliest jazz room, and the usual overflow crowd has grown uncharacteristically silent. They’ve turned from drinks and conversation to focus on violinist Zach Brock. Just the sight of a fiddler in a jazz club might well prompt such attention; you can count on both hands the number of notable jazz violinists. But there’s more to it than that.

Eyes closed, half-entranced, Brock has launched into a lengthy cadenza that has transfixed the audience. The rest of the quartet has dropped out, and the only sound is that of Brock’s increasingly virtuosic passages, building in complexity and emotional intensity to a heady peak. When the band finally re-enters to break the spell, the ovation seems to shake the floor, as if the entire room had been holding its breath and can at last exhale all at once.

“He’s studied the whole lexicon of jazz and classical music, and he encompasses it all,” says pianist and jazz composer Phil Markowitz; he and Brock co-lead this quartet, which they founded in 2012, shortly after Markowitz (22 years Brock’s senior) first encountered the violinist.

“I had never heard anybody play the instrument that way,” adds Markowitz, who had long hoped to find a violinist for whom he could compose music that fuses jazz and classical concepts. “He smashes all the previous conceptions of jazz violin.”

Photo by Janis Vogel.

Both musicians live in New York, but they have come to Chicago for a weekend engagement celebrating Perpetuity, their quartet’s initial CD. Considered by many to be the outstanding violinist of his generation, Brock ’99 has led or co-led nine previous recordings and played on a score of others, earning plenty of praise in the process.

Veteran Los Angeles Times critic Don Heckman wrote, “Add Brock to the small list of players finding ways to bridge the potentially hazardous chasm between the violin and jazz.” The well-known pianist and vocalist Patricia Barber ’96 MMus has spoken of his “fiercely charismatic presence onstage.” And the storied bassist Stanley Clarke, in whose band Brock has often appeared, references yet another jazz legend in relating how he phoned the great French violinist Jean-Luc Ponty to ask, “So, who’s the new cat? Who’s got the stuff?” — to which Ponty immediately replied: “Zach Brock.”

Brock grew up in Lexington, Ky., but contrary to one report, he does not down a shot of hard Kentucky liquor at each performance. (He, however, possesses a sense of humor dry enough to have engendered that canard. When an interviewer asked if his geographic roots meant he loved bluegrass, Brock says he joked, “ ‘Oh yeah, and I drink a glass of bourbon before each set.’ She thought I was serious.”) Brock’s grandfather played trombone and ran a music store still operating in Lexington; Brock’s mother plays piano and teaches voice and singing, and one of his earliest memories is of “hanging out near our old upright while she was teaching and practicing.” His father was a trumpeter who switched to guitar during the folk-music boom of the ’60s before entering law school. But now he plays trumpet two to four hours a day. Brock started playing violin at 4 and began improvising with his parents in a folk-music context while still in elementary school.

Brock gravitated to Northwestern’s Bienen School of Music to study with Myron Kartman. “He was a teacher of some notoriety — even infamy,” Brock says with a smile. “He has a very big personality. But once you got into his studio, he was very protective; for an undergrad just coming into the school, it was almost like having another father figure, or an uncle who’s got your back.”

The Long Road

On Oct. 30, 1992, about six weeks into his sophomore year, Brock was bicycling through Evanston to visit a friend when a car plowed into him at Ridge and Colfax and left him splayed in the street. Attendees at an early Halloween party heard the hit-and-run accident and rushed to help.

“If they hadn’t come out and protected me,” he says, “I probably would have gotten run over.” He couldn’t stand, let alone walk: The collision broke virtually every bone above the ankle in his left leg. His femur had burst through his trousers; his kneecap had shattered into eight pieces. “My tibia and fibula were bent like a banana,” he says. (Providentially, his head, neck and arms escaped any serious harm, which meant he could still play the violin.)

Over the next three years Brock underwent a series of surgeries to correct the damage. “A lot of my rehab was just getting my knee to bend enough that I could walk without a limp,” he explains: Every muscle group in his leg was hobbled by scar tissue. But now, seeing him stride onstage to stand for several hours in front of his band at the Green Mill, you might never suspect the carnage inflicted decades ago.

Brock recuperated at his parents’ home but longed to get back to Northwestern. “I was completely devastated, emotionally as well as physically,” recalls Brock. “I basically lost all sense of self. I needed my friends, and I needed to keep playing the violin. But I couldn’t be in school, and my friends were graduating.”

He finally headed back to Evanston in the spring of 1994, but it took until the fall of 1995 before he could resume a full course load. During this time, his teacher, professor Kartman, rose to the occasion, earning the musician’s ongoing admiration.

“The violin itself is not an easy path, but he chose to finish what he started. And he remains one of the more outstanding students I’ve ever taught. He is naturally gifted. And he has made the most of his gifts.” — Professor Myron Kartman

“Kartman knew that what I needed was a peer group,” Brock says. “As soon as I got back to Evanston, and for the entire time until I could get back to classes, he gave me weekly lessons and let me keep coming to group lessons — and he never asked for a penny. So I was able to keep playing and to keep studying with him; in terms of lesson hours, I got the equivalent of a master’s degree plus.”

The admiration runs both ways: Kartman, a professor emeritus of music performance who is still active at 82, marvels that Brock made it back to school at all. “I thought it was a tremendously courageous path for him to follow,” he says. “The violin itself is not an easy path, but he chose to finish what he started. And he remains one of the more outstanding students I’ve ever taught. He is naturally gifted. And he has made the most of his gifts.”

Classical Training

Brock finally completed his degree in 1999, four years late, but the delay was well spent: He honed his skills and met the woman who would soon become his wife — a School of Communication theater major (now filmmaker) named Erin Harper ’96. And, he says, “By then I knew what I wanted to do” — play jazz for a living. But this required a lot of catching up, and not only because of his accident.

Brock had entered the music school when the jazz program was in its infancy, and it had no place for a violinist; the only performance degree for that instrument came with a classical-music pedigree.

But Brock’s interest in jazz had convinced him that the conservatory-level training at Northwestern would serve him well.

“The more stuff I listened to,” he explains, “the more I came across things on the violin that I needed to deal with” — issues of technique, timbre and phrasing exposed by his attempts to emulate the horn players he respected. He learned to play more complicated, truly “violinistic” music — which has turned out to be the distinguishing aspect of his work.

Northwestern still allowed him some jazz training, however informal. Kartman encouraged Brock’s jazz proclivities — a rare event among classical-music faculty at any conservatory — in part because of the huge potential he recognized in the young violinist.

“As artists, we tend to use very little of what we learn,” Kartman says. “So much is discarded. But Zach Brock has the ability to use everything he learns.”

Kartman introduced him to Mike Kocour ’01 MMus, a jazz pianist teaching at the music school, who began inviting Brock to his office for off-hours instruction. And he soon came under the wing of Orbert Davis ’97 MMus, then earning his master’s degree at the school.

Davis had already achieved a national reputation for his small bands and had just begun to arrange for strings; tutoring Brock in jazz soloing, he got much from Brock in return.

“I brought along all the music I was writing for strings, and as I was teaching him to play like a trumpet, he was showing me bowings [violin techniques that a successful arranger needs to know]. It was mutual,” Davis says with a laugh. “As I taught him, he taught me.” (Davis, who would go on to create the 55-piece Chicago Jazz Philharmonic Orchestra, made Brock a special guest for his artist-in-residence concerts at the 2011 Chicago Jazz Festival.)

While finishing his degree, Brock took one more step toward a fledgling jazz career. He got a “day job” in Evanston to make ends meet.

“I was working at Café Express, on Main Street, which hosted guitar duos. And I would see these guys playing while I was getting vibed for not having fresh-squeezed orange juice for people — and one day I just quit. I went back to my apartment and got my violin and came back to the café and asked if I could sit in. And that’s how I met Aaron Weistrop.”

Weistrop, recently graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio, had formed a band puckishly named the Spazztet. “Aaron was like, ‘I’ve got this band, and I want you to play on my record, but if you want to be a member, you have to write original music.’

“And I wanted to belong, so I just started writing.” Thus began Brock’s career as a jazz composer. With the Spazztet and in other groups, Brock stayed busy, performing at Evanston venues such as My Bar on Sherman Avenue and Pete Miller’s Steakhouse and at Chicago clubs such as Quencher’s, Martyrs and Katerina’s.

Brock left the Spazztet around 2000 and formed his own group, The Coffee Achievers, which toured beyond Chicago. This had its downside.

“I had some dark, dark times,” he says, recalling days of setting up logistics for nights of disappointing gigs. “I mean, to go through all that bullshit and then drive an hour and a half to the middle of nowhere, pondering, ‘Why am I doing this?’ — I actually thought it might be hurting my music. I once drove to northwest Indiana to play in a string section backing up the band Kansas. That was actually kind of fun because it was so ridiculous — and I did get to play ‘Carry On My Wayward Son.’ ”

The Coffee Achievers released several albums on Brock’s own label (Secret Fort Records); now people started knowing his name and touting his talent. He soon came to the attention of Stanley Clarke, one of the few jazz artists who can command arena-sized audiences, and for several years Brock cut a familiar figure in Clarke’s touring band.

Armed with that experience, and prompted by curiosity and desire, Brock and his wife moved in 2005 to New York, jazz capital of the world.

Musicians from everywhere flock to New York, almost as a rite of passage, although Brock had never considered it a necessity. One determining factor was his wife’s decision to change careers from dance and work as a Pilates instructor to documentary filmmaking. And Brock had traveled there enough, for gigs and occasional lessons with teachers based there, to have grown comfortable with the city.

“Talking about it now,” he says, “it’s funny — I can’t really give you a good reason for the move. It was a bit impulsive. But I think I felt that if I didn’t deal with it, it would hang over me, psychologically.

“So we moved from this amazing place on Ravenswood in Chicago — which had two bedrooms, two bathrooms, gated parking and a rooftop deck — to a 500-square-foot, roach-infested, mouse-infested, one-bedroom apartment in Prospect Heights [Brooklyn]. And our rent was ‘only’ twice the price of the mortgage we’d been paying.”

It took several years, a new apartment and steadily improving opportunities for Brock to feel that he had made the right move. But it has certainly boosted his visibility — especially in other countries.

“It seems that the overseas promoters, who are going to bring you over for gigs in Europe and Japan — where you need to play to actually make a living — when they come to the U.S. to check out bands, they just stop in New York to do one-stop shopping, you could say.” (At publication, Brock had recently completed an 11-day tour of Austria and Germany led by singer/pianist Stephanie Nilles, with his other main group, The Magic Number.)

Sticking with the Four-String Violin

Brock has had several turning points in his career. He mentions his early partnership with Aaron Weistrop, as well as his decision to attend several summers at the Banff International Workshop in Jazz and Creative Music in western Canada. Most recently, he references Phil Markowitz as a serious mentor; of their current quartet, he says, “I don’t play music like this with anyone else. Phil is just hugely inspiring to me.”

One vital insight came from Stanley Clarke, and it led Brock to abandon the five-string violin — a 20th-century creation designed for rock and jazz — and refocus on the four-string instrument that has been the standard since the instrument’s invention in the 16th century.

“Stanley was telling me about how conscious [Jean-Luc] Ponty was about ‘controlling the range’ of the instrument, as he put it. See, when I would play the five-string violin, I would use the bottom string for some low, smoky, saxy-sounding thing. But I was not really playing down there.” Essentially, Brock was using the fifth string as an adjunct — merely for effect. Clarke’s comment helped Brock realize the dead end that awaited if he kept trying to make the violin something it was not.

Another “aha” moment took place earlier, shortly after Brock had left Northwestern, when he took a lesson from the world-renowned guitarist Pat Martino. “I was playing all my bebop stuff, which was fine, but at the end of the lesson, he said” — here Brock does a dead-on impression of Martino’s deep, mellifluous voice — “he said, ‘So, you know you have to be a bandleader, right?’ See, I wanted to put my blinders on and think that if I just wished hard enough, tried a little bit harder, people would think I’m a saxophonist, and they’d just hire me for their band, and then I’d get to do the thing you do in jazz — you get to go out with a bandleader and learn stuff from them.”

Martino had verbalized something Brock had begun to suspect: that it was futile to play the violin like a saxophone, because if that’s what a bandleader wanted to hear, he could simply hire —a saxophonist. From that conversation Brock glimpsed a truth he has pursued to this day: he plays an instrument uncommon in jazz, and only by accepting and even emphasizing the violin’s idiosyncrasies — its very violin-ness — would he carve out his own sound and concept. “It’s more difficult,” he admits, “but a lot more satisfying. I’m now starting to feel like I know how to practice so I can become more expressive on the instrument.”

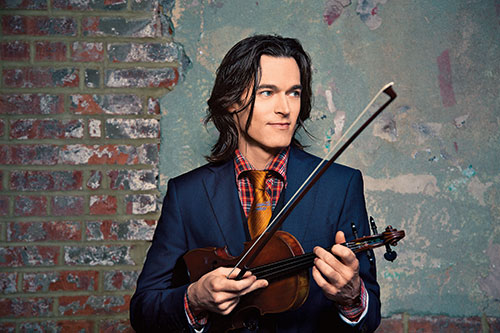

Zach Brock, photographed in Brooklyn with his Leandro Bisiach violin (Milan, 1895), fuses jazz and classical music like no other violinist of his generation. Photo by Jimmy Katz.

There’s a legacy in the small world of jazz violinists, and it has a tangible symbol. In 1937 Michel Warlop, the French violin prodigy and early jazz star, presented his instrument to the brilliant improviser Stéphane Grappelli, as a gesture of “passing the torch” to the next generation of jazz fiddle players. Grappelli paid it forward, to Ponty, a jazz-rock pioneer, sometime in the late ’60s or ’70s. In 1979 they together awarded it to Didier Lockwood, a French-Scottish violinist who today is nearing 60. Brock, who recently turned 40, would seem a worthy recipient to maintain the tradition.

“Nope, nobody gave me a violin,” Brock replies. “In fact, Lockwood kept it.” So much for tangible symbols. But on any given night, as he propels his music into territory new for himself and for jazz, Zach Brock — for all intents and purposes — has that fabled Warlop tucked securely under his chin.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email