by Ying Zhu Chin When Starbucks finally came to Taiping, that confused place with the infrastructure of a small town and the population size of a city, K. felt that she could now better decide whether or not to leave H., and whether to be full of hope or devoid of it.

All over Taiping there was a festive mood that hung fog-like around the surrounding mountains. At the brand new Starbucks store a long queue of people spilled onto the street. They took turns holding the front door open as the line advanced. Air-con poured out of the open door.

K. was there to see H. Looking at her reflection in the glass storefront, she thought about the arrival of McDonald's years ago, when Taiping had been this excited too. H. and K. had gone there on their first date, riding on the wave of exhilaration and feeling rather grand. They were young enough for McDonald's to be swanky. Or perhaps it was not their age but where they grew up that made McDonald's swanky; she didn't know.

She didn't know a lot of things, and she was the first to admit it. But here was Starbucks — Taiping was changing — maybe she should, too.

She saw H. when it was almost her turn to hold the glass door open. He was almost at the counter but still staring at the mounted beverage menu intently, indecisive as usual.

Taking one last look, K. stepped out of the line and walked away into the morning heat.

On her way home she tapped the steering wheel and started listing reasons that might help her make a decision.

Reason: She was older

She was getting older, older than when she first fell in love with him. And she was older than he.

Perhaps not many people cared anymore if the woman was older than the man, but she thought H.'s mother cared.

The first time K. went over as his girlfriend, his mother treated her like a stranger, even though she had essentially grown up under his mother's eyes. His father, on the other hand, acted as if nothing had changed. Their charade reminded K. of her grandfather, who still talked about Malaysia as if it were Malaya, who asked her name every time she visited.

Dinner was two meat dishes and one vegetable dish, H.'s mother's preparations. Throughout dinner the mother coldly answered whatever question K. put forth as small talk, but afterward, doing dishes in the kitchen while the men watched TV, H.'s mother leaned her face close to K.'s, her body rigidly held away, and offered to teach K. how to make H.'s favorite dish. It was supposed to be kangkung with belacan. Months later, curled up in H.'s lap and making small talk, she found out that it was not.

Reason: She had already spent one year and wasted three on him

Round up.

Together they had seen many things. They saw McDota, the local rip-off, close down. K. had had her seventh birthday party there; there was a picture of little K. pushing little H. away from her cake, an old-style picture with rounded corners tucked into a yellow Kodak album kept in a drawer in K.'s house.

K. knew it was her seventh birthday because of the candles on the cake. She had no memories of the event.

He stopped being her boyfriend when she was nineteen, some weeks before their first anniversary. He appeared to be honest and forthright about his reasons: he had fallen in love with another woman, a girl younger than he.

After the breakup she found it easy to deceive herself, since she saw him just as frequently as when she was his girlfriend. It made her wonder why they had spent time so inefficiently before he had to run between two women. She thought often about the lost time, or the missing time — she didn't know what to call it.

Except she now met him in secret, away from the public eye. Taiping was about twenty minutes large (by motorbike), and the probability of H.'s (real) girlfriend catching K.'s hand in his was significant. So they rendezvoused mostly at her place, when her parents went away on business trips. On weekends they drove to Ipoh or Penang, which, unlike Taiping, had malls, and there, where shoes and heels and boots squeaked on shiny smooth mall floors, he held her hand, put his arm around her waist, nuzzled her ear, fed her from his plate.

Other than that, life seemed to go on as before. She tutored a family friend's children in the morning and left after lunch to visit him in the factory he worked in. Often she stopped on the way to get him a plastic bag of Milo, tied shut with raffia string, a straw poking through. She sat in the empty manager's office and watched him work on the other side of the large glass rectangle. Sometimes she went over her students' homework. Sometimes she had a magazine. Most times she merely sat and followed his movements, waiting for that flash of a second when his arms strained against a handle on a mysterious machine.

After a while K. started driving to his place on certain nights at a certain hour. The hour was his (real) girlfriend's self-imposed curfew, since she had to get up early for school. The girl was in Form Five at the Convent, long stripped of nuns after the British left. K. knew what the girl looked like. Sometimes her car would have been long gone from H.'s yard. Other times K. parked down the street, turned the engine off and sat in the darkness, waiting to watch the girlfriend leave.

One night, by the light of a streetlamp, K. saw that his girlfriend had changed her hair, dyed it some shade of brown.

Round down.

Reason: She had never left Taiping

After a year of not being H.'s girlfriend, K. was accepted into the University of Malaya. She refused to go. Her parents could not understand why she wanted so badly to throw her future away. They pressed her until she told the truth: she did not want to move away from Taiping.

But there is nothing here, K.'s parents said. Don't you want to leave? All your friends have moved away, anybody who can do it. Your cousins, the neighbor's kids, everybody. If you won't go to university, at least go to Kuala Lumpur, or Penang, or even Ipoh, where the jobs are better and you can make more money. Don't stay here. Here there is nothing.

She persisted, continuing to live in her parents' house. She started thinking of herself as a humble small-town girl with no ambition, no drive, a simple soul who wanted nothing more than to avoid the brutality of (real) cities, to live and die in the place in which she was born.

She would have been the first in her family to have a tertiary education.

On sweaty afternoons when it got so hot he pushed her away on the bed she watched the standing fan shake its head at her, slow no no no. Often after sex he would be so comfortably stretched out, immobile, that he would not clean himself up, staining her sheets. Once, rolling off her and almost falling off the bed, he noticed a smear of period blood that K. had been unable to wash out. He asked her if she had been eating chocolate in bed. After that they always did. Cadbury milk chocolate. Sometimes with embedded nuts, sometimes not.

They had planned their first time carefully, back when they were still an official couple. Not wanting to get caught, they drove to Ipoh for a hotel room. Their first attempt was not successful; they did not time the alternating of kissing and undressing right. When he hurt her nipples, he confessed that he was a virgin but did not ask K. if she was one, too.

After that first attempt neither of them felt like trying again, but they had paid for the hotel room and did not want to waste. To delay sex, she suggested getting food. They sat in a semi-open-air coffee shop, where he self-consciously ordered a Tiger beer and she shifted uncomfortably on the backless plastic stool with a round hole in the center of its seat. Her coffee came in a clear glass that rattled against its saucer, condensed milk lumping at the bottom.

Around dinnertime they returned to the hotel room and managed to have (real) sex. It was the first and last time they would do it in an air-con room, and sometimes, on hot afternoons in her bedroom, K. would try to bring that first time back — the atmosphere sterile with air-con fumes, stretched tight over her skin, holding her sweat and cries in. It would without a doubt be the worst sex she would have in her entire life. After it was over, H. held her very gently and apologized again and again for the pain. He had never been as tender to her since.

Driving back they started listing places in Taiping they thought they could safely have sex in, since they could not afford a hotel room whenever they wanted to be intimate (which they imagined, at that moment, would happen very frequently). In the end they were no more original than any other couple in Taiping, falling back to the reliable shrubbery in the public lake garden. The dirt and pebbles and outstretched roots of trees hurt her back at first, but she became used to it over time. Sometimes they drove to the grounds of rich men, whose properties were so large that they could not keep track of cars that parked in dark corners for half an hour at a time.

On one of the days when her parents were out of town, H. sat up on crumpled sheets and told K. that his (real) girlfriend was thinking about leaving Taiping for Johor, where a friend had connections to a lucrative job. That night K. had a dream about the girlfriend being ejaculated from Johor, the tip of Malaysia as Asia's penis.

Reason: She was his first cousin

All they knew was that his mother had been adopted, making K. and H. first cousins by title but not by blood. K.'s father, H.'s mother's brother, would elaborate no further either.

H.'s parents also refused to tell him how they met. Whenever H. asked, they pretended that he was not in the room, did not exist, as if by questioning their union he himself would cease to have been conceived.

He could be from anywhere, have any kind of blood in him. K. always thought his skin color and hair type very slightly unusual. He could have been destined for another name, another race, another religion — and thus forever barred from her — but here he was! The fatefulness delighted her.

Taiping is too fucking small, K.'s father had muttered in disgust when he learned about K. and H.

K. had very few memories of H. as a child. Everybody was happy when they broke up. Everybody was happy, too, when the cousins appeared to harbor no hard feelings and continued to be friends. It saved a lot of pain and awkwardness at family gatherings. At one such gathering H.'s mother went so far as to whisper to K. that the other one did not measure up to her.

Sometimes when K. and H. were bored they would speculate about the (real) identity of his mother and how his parents had met. In one version his mother was a prostitute who had fallen in love with his father, but shame and a sense of honor prevented H.'s father from marrying a whore. In the end the lovers begged K.'s grandfather, a client behind on his dues, to adopt H.'s mother and graft onto her a legitimate family background.

Reason: She was losing

— Hair.

In school there was a girl who showed up one day with her previously armpit-length hair cut short. K.'s classmate whispered to K. that it meant the girl had lost love, probably due to being dumped. According to the classmate, the haircutting was "a symbol."

After she ceased to be a girlfriend, K. decided never to have her hair cut again. Her hair grew longer and longer and became heavier and heavier. More and more of her hair fell; her scalp could not carry the weight.

H. sometimes hurt her when he pressed his palms down onto the bed to support himself, catching her hair under his hands, yanking. He complained about the loose hair strewn over the sheets.

— Friends.

The ones she lied to resented her vague excuses for being busy at odd hours of the day.

The two (real) friends she did not lie to were furious at her for letting it happen to her, "it" being at various times incest, mistresshood and, more generally, self-destruction.

One of the two wanted her to stand up for herself, to reject the second-class, leftover scraps of love, but K. seemed unable to frame it that way. "What's wrong with small desires and asking for very little?" she asked. "It's much easier to be satisfied this way." She said she was thankful and counted her blessings that he had heart enough to not abandon her even though he had moved on to someone else.

The other friend staged an intervention of sorts and tricked K. into going on a date. The man was a well-connected businessman. K. first learned about Starbucks' impending arrival in Taiping from him. He waved his hands around, telling K. about the also impending arrivals of Sushi King and a real, honest-to-goodness cinema, something Taiping had not seen for many years. Times are changing, he said. Remember when that company offered to build a casino on Maxwell Hill but the authorities refused to let them do it? Because they were afraid of hurting nature or whatever? We missed our chance to really develop into a real city then, but look, we're doing it after all, and by ourselves, too. Soon no one will be able to call Taiping a "small place" anymore!

One night, half-reclining on a sloping tree trunk in the lake garden, K. heard her phone ring. Later, when she was able to check her voice mail, she found that it was one of her two best friends, obviously drunk, calling to tell K. that she was the shame of women everywhere, allowing herself to be manipulated by a youngster so completely. Do you know what century this is, the friend asked. Do you know that women have dignity?

I would rather have love than dignity, K. murmured to the phone. Maybe I am just a small- town girl. The un-launched accusation hung in the air, and K. answered it: Yes, it is love.

When K. got home, the first raindrops were splattering her windshield. K. ran out of the car and rushed into the yard, yanking her family's clothes off the lines stretched out between two trees, pegs flying every which way. Her father pulled in a minute later, slamming the car door and grumbling, "Open up a Starbucks and suddenly there's a traffic jam everywhere, everybody wanting to pretend that they are city folk who can waste RM12 and three hours in line for kopi without even condensed milk in it. Taiping is just too fucking small!"

Inside the house, K. dropped the armful of damp clothes on the living room couch and picked up her handphone to call her best friends.

"Do you want to go to Starbucks tomorrow?" K. asked.

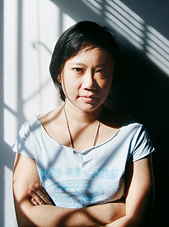

"Oh, I'm sure it's nothing special and I won't like it, but it's something new."  Ying Zhu Chin (McC07) was born in Malaysia and lived there until she left at 19 to pursue an engineering degree at Northwestern. While at Northwestern, she was accepted into the undergraduate creative writing program, where she studied with writers Averill Curdy, Brian Bouldrey (WCAS85), Reginald Gibbons, Anna Keesey and Robyn Schiff. Chin is currently at New York University on scholarship, writing her master's thesis toward an interdisciplinary degree in humanities. She lives in Brooklyn. Ying Zhu Chin (McC07) was born in Malaysia and lived there until she left at 19 to pursue an engineering degree at Northwestern. While at Northwestern, she was accepted into the undergraduate creative writing program, where she studied with writers Averill Curdy, Brian Bouldrey (WCAS85), Reginald Gibbons, Anna Keesey and Robyn Schiff. Chin is currently at New York University on scholarship, writing her master's thesis toward an interdisciplinary degree in humanities. She lives in Brooklyn.

|