CHARLES AND GRETCHEN SIGWART

CHARLES

Then: PhD student in Biology studying physiology and toxicology; BS in Aeronautics and Astronautics from MIT; Served as NSBE chairman of Information Committee, and later, as Chairman of NSBE.

GRETCHEN

Then: PhD student in Environmental Engineering, a division of Civil Engineering at Northwestern; Gretchen served on the Information (Communication) Committee. She and Charles were responsible for publishing the NSBE monthly newsletter, and together transcribed the audio (an enormous task) from the Project Survival speakers, for the book titled, "Project Survival."

CHARLES

Now: After completing his PhD at Northwestern, he did postdoctoral work in toxicology at Kettering's Laboratory in the Department of Environmental Health at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 1976-1980. As the funding for research in toxicology was drying up, Charles switched his study area to Computer Science. He taught Computer Science at Central Michigan University and Northern Illinois University. As a disability rights activist, Charles has written articles and led seminars on adaptive technology for people with disabilities, taught a course on neuroscience to music therapy students, and is an active participant in local service agencies. He is the co-author of a book on Software Engineering with Gretchen L. Van Meer Sigwart, fellow NSBE alum. Recently retired, Charles runs a small used bookstore in DeKalb, Illinois.

GRETCHEN

Now: After graduation, she worked as a postdoctoral researcher for a major study sponsored by the EPA, at Kettering (University of Cincinnati) on the effects of pollution. She later became the first woman professor of Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh; taught Engineering and Computer Science at West Virginia University, Central Michigan University and most recently at Northern Illinois University, where she retired in 2004. Dr. Van Meer has coauthored two textbooks in computer science, including Software Engineering, with Dr. Charles D. Sigwart and Dr. John C. Hansen. She is interested in the area of adaptive technology for people with disabilities, and has written articles and presented seminars on computer aids for visually impared persons; in addition, Gretchen is an avid folk harper. Gretchen and Charles are the proud parents of daughter, Julia, a marine biologist on faculty at Queens University in Northern Ireland.

Memories of NSBE and Project Survival:

Gretchen L. Van Meer met Charles Sigwart at a course offered through Northwestern's "Free University," a program in which anyone on campus could offer a non-credit course to anyone interested. Charles, a graduate biology student, had organized a course, "Ecology, Pollution and Society." Gretchen had signed up for the course, and the rest, as they say, was history - the couple began dating and were among the first members of NSBE in the fall of 1969.

"We pulled this (Project Survival) together so quickly - we met the first week of December, and decided to go for it. School was about to close for winter break. We had one meeting to plan it, but people worked on it throughout the break. Project Survival was a major event. Northwestern had jump-started the season for Earth Day."

"One aspect that was different about NSBE was that the group was dominated by graduate students. They came from many parts of Northwestern University: Environmental Engineering, Biology, Chemistry, Bio-Medical Engineering, Law, and a scattering from other departments.

An environmental engineering professor, Wesley Pipes, became the official faculty advisor to the group. Only about a quarter of the core group was made up of undergraduate students. In early fall there were about 20 in the group. By the beginning of December there were about 50.

The group grew as a coalition of committees. It started as a small group of issue oriented committees meeting as a whole, monthly. The water pollution group, air pollution group, etc each met separately. The structure was formalized with an executive committee composed of chairs of committees, plus an executive committee chair, a secretary, and a treasurer. It was decided that anyone who organized a committee around an issue or a project could apply to the executive committee. If it got a majority vote it became a recognized part of the group and its chair joined the executive committee. A fundamental principle was that any public action of any group had to be approved by a majority of the executive committee. The executive committee grew or shrank depending whether particular committees progressed or died out."

"Our committee was responsible for the monthly newsletter, and anything that had to do with getting the word out on what we were doing. After the Project Survival event, we were drafted to be copy-editors for the transcript of all the speakers. Someone had donated the use of an offset printing press out in the suburbs. We were dispatched there to learn how to use it, and got to work running the press. We printed 100,000 flyers. There was so much going on. Charles was the office manager, and when we published the results of the phosphate list, it seemed the phone would never stop ringing. It was quite a time."

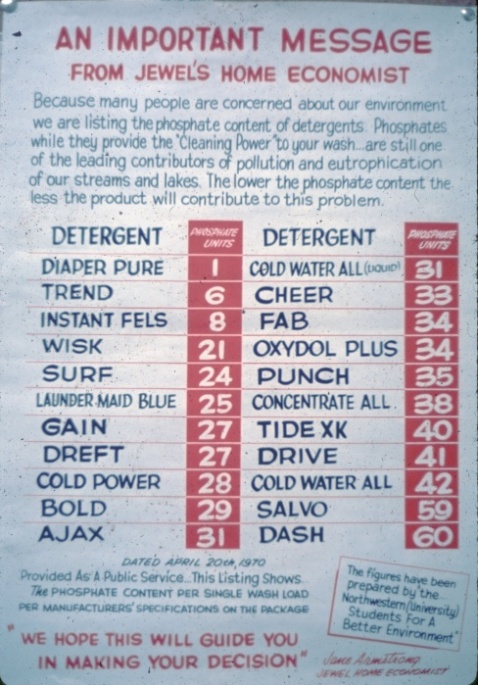

About the Phosphate List:

"The issue was how to get people aware of the danger of phosphates in their detergents. Casey, Wes Pipes, George Antos and others - grad students and tech volunteers - began with 5 brands of detergent; the list eventually grew to 25. They measured how much phosphate was released into the water with one load of laundry. There were stats out there, but they weren't useful for consumers - they were too abstract. They decided if people knew the difference in brands they would be able to choose the right ones and force the industry to deal with this. They did tests and calculated the amount of PP in a wash-load so the public could understand. Plain and simple.

Then the question was, how do you get people the list? The newspapers wouldn't print it - it was too controversial, there was too much pressure from industry.

When we had completed the research, we printed up the flyers. These went out to women's environmental groups, and other concerned individuals. Finally, Casey and others got a meeting with the management of Jewel and talked with them. Jewell decided to get out in front of it, and placed a full-page ad in the Chicago Tribune with the phosphate list. They posted the list in their stores, so shoppers could see the levels of various brands. The rest of the grocery chains soon followed.

The list made sense to consumers. It all rested on the fact that the technical work was first rate - accurate without questions. If anyone had caught us with errors, we would have lost all credibility. The accuracy of the work of Northwestern's Tech graduate chemistry and engineering students was critical and it was top rate.

In less then a year, federal legislation was passed limiting the amount of phosphates in detergent."

"This was real grassroots politics. The people who organized Project Survival moved from public awareness to policy within two years."