Reel Life

Elizabeth Canning Blackwell (C90) is a freelance writer in Skokie, Ill.

Editor’s note: University Library will host an exhibit on the Patricia Neal collection Jan. 10–March 22, 2013.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Ever wonder about those strange designations we use throughout Northwestern to identify alumni of the various schools of the University? See the complete list.

Find Us on Social Media

Movie star Patricia Neal led a life full of joy and woe. Now you can explore her story at University Library, thanks to her family’s donation of her papers and memorabilia.

Patricia Neal took on many roles in her life: Northwestern theater major, Hollywood actor, mother of five, Academy Award winner and stroke survivor. Through professional and personal challenges — and there were many — she prided herself on bringing a sense of emotional honesty to her work. Now, two years after her death (see Passings, winter 2010), Neal’s family has honored her openhearted spirit by donating her personal papers and memorabilia to Northwestern University Archives.

The collection, which fills more than 70 boxes, encompasses a life both public and private, from fan mail and publicity photos to family birthday cards, legal correspondence and news clippings. In all, it represents a significant addition to Northwestern’s holdings, says University Archivist Kevin Leonard (WCAS77, G82). “It’s an amazing collection,” he says. “It will help researchers better understand both Ms. Neal’s accomplishments and the performing arts community of her time and also appreciate pressing issues relating to illness and recovery, loss and love, faith and determination.”

Images and documents courtesy of University Archives. Photo by Gary Gantert.

Neal’s life, as she was well aware, could easily have been reduced to a tabloid drama. But her story is ultimately one of survival, of both body and spirit. Her autobiography, As I Am (Simon and Schuster, 1988), was praised by critics for its ruthless honesty.

Neal’s children believe their mother would have been thrilled to see her mementos preserved for posterity. “She loved Northwestern,” says Neal’s daughter Lucy Dahl. “The University held a very special place in her heart, and she spoke of it often. She maintained very close relationships with her sorority sisters throughout her life, often reuniting with them at her home on Martha’s Vineyard.”

Born in 1926 in Kentucky, Neal (C47, H94) was raised in Knoxville, Tenn., the daughter of a coal-company manager. The Northwestern collection includes her original baby book, with a lock of her blond hair slipped between the pages.

Enthralled by performing from a young age, Neal dreamed of heading to New York after high school but agreed to her parents’ demands that she go to college first — as long as she could study drama. She arrived at Northwestern in fall 1943, and by her sophomore year she had already made her mark on campus. She was crowned Syllabus Queen in a campuswide beauty pageant and was cast in drama instructor Claudia Webster Robinson’s production of Twelfth Night.

Most important for her future career, Neal also began studying with legendary acting professor Alvina Krause (C28, GC33), whom she later described in her autobiography as her champion; Neal’s daughter Lucy says her mother adored Krause and remembered her fondly for the rest of her life. Neal spent a summer at Krause’s theater company in Eagles Mere, Pa., and informal meetings with talent scouts there convinced her to leave college for New York.

Soon she was living in a one-bedroom apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with three Northwestern friends, scraping by through waitressing and occasional understudy work.

Then came her big break: a role in Lillian Hellman’s play Another Part of the Forest, for which Neal won a Tony Award and landed on the cover of Life magazine. Courted by major movie studios, Neal moved to Hollywood at the age of 21 and starred in numerous films in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Although none brought the kind of success she had envisioned, The Fountainhead (1949) proved to be a milestone in her personal life, for it was during the production of this film that she met and fell in love with actor Gary Cooper. For the rest of her life she kept mementos of their time together, including a dressing-room key engraved with his name, which is now part of the Northwestern collection. But her multiyear affair with the married actor took a toll on Neal’s career. As she remembered in her autobiography, “I was no longer the young darling of Hollywood. I was the unsympathetic side of a triangle.”

Ultimately, Neal left both Cooper and Hollywood and returned to New York, where she met and married British writer Roald Dahl. Although she never abandoned acting completely, she put her desire for a family first, eventually settling with Dahl in England. Passports in the University Archives collection, issued in her legal name of Patsy Neal Dahl, show a smiling mother surrounded by her children, the stamped pages evidence of frequent flights between New York and London.

Although Neal valued family above career, her domestic life was far from tranquil. In 1960, just after she finished filming a small role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, her 4-month-old son, Theo, was nearly killed when his baby carriage was hit by a taxi. Suffering from a life-threatening head injury, he ultimately endured eight different operations before recovering. Two years later came an even worse blow: Neal’s oldest child, Olivia, died at the age of 7 of complications from measles.

Neal’s autobiography describes in searing detail the devastation of that loss. But, as she wrote, “I was afraid that as a family we were doomed if I did not keep us moving emotionally and financially. … We had to have the stability that comes with knowing life goes on.” It was then that she was offered the role that would bring her an Academy Award: that of Alma Brown in Hud, alongside Paul Newman. (Pregnant with her daughter Ophelia, she was unable to fly to Los Angeles to accept the award in person.)

Neal’s career appeared to be headed for a comeback when tragedy struck again: In 1965, at the age of 39 (and three months pregnant with her daughter Lucy), Neal suffered a series of devastating strokes. It took years of grueling rehabilitation before she was able to move and speak confidently, and her incapacitation prevented her from being a hands-on mother to her children, a loss that strained the entire family. Her determination to recover, however, led to a new, real-life role: that of inspirational speaker. Even as Neal struggled to hold conversations with friends, she memorized speeches in which she offered hope to other stroke survivors. She was even able to return to acting, earning a second Academy Award nomination for her role in The Subject Was Roses (1968).

Although Neal credited Dahl’s tough-love approach with helping her regain her independence, their marriage ultimately unraveled when Dahl began an affair with a family friend; the marriage ended in 1983. Forced to reinvent herself once again, as a single woman in her mid-50s, Neal formed an unlikely friendship with Gary Cooper’s daughter, Maria, who steered Neal to the Catholic Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Conn. Under the guidance of the prioress, Delores Hart (a former movie star herself), Neal came to peace with her past. It was at Regina Laudis, she later wrote, “where I would understand, through my belief in love, the value of suffering — and where I would find that remembering is the root of hope.”

Images and documents courtesy of University Archives. Photo by Gary Gantert.

Neal’s papers and memorabilia give a tangible connection to her remarkable life. Boxes of correspondence include a letter written by Ronald Reagan, her co-star in her very first film, John Loves Mary (1949), written from the White House as he recovered from surgery: “Whenever I needed courage, I thought of you and the strength you showed during your illness. With such an example, how could I not get well!” Or another from her Hud co-star Paul Newman, asking her to be interviewed for his biography: “Don’t feel you need to hold anything back or censor yourself, even when the areas under discussion may include thoughts or feelings you’ve never expressed before out of regard for me. The truth will be the best thing you can give me.”

There are also love letters from Gary Cooper (unsigned, for he and Neal were careful not to put names on their correspondence). But the feelings expressed are so vibrant that it’s clear why Neal chose to save them: “There never was a more welcome sound than your angel voice just a minute ago. … Thank you, thank you my darling for being home when I called and making everything in this world look so beautiful. I love you, I adore you.”

There are remembrances of family as well: honeymoon photos; pictures of family holiday gatherings; letters from her daughters (one beginning “Most treasured Mummy … ”); and cards from grandchildren to “Mormor” (the Norwegian term for Grandma, a nod to the Dahl family’s Scandinavian roots).

Tucked amid the glamorous headshots and not-so-glamorous tax returns, there are also unexpected moments of grace. Underneath an invitation to her son’s 30th birthday party — hosted by her ex-husband and his new wife, in the home that used to be hers — is a copy of the letter Neal wrote in response: “Everyone thinks, and now I agree, that the time has come to put my bitterness aside. … I offer you both my genuine love and support; and I pray that we are able to reach this point of understanding.”

Next in the stack is Dahl’s response, almost giddy with relief: “We both want to say how grateful we are for your splendid and generous gesture of friendship and we return it to you in full.”

Neal’s papers offer a firsthand glimpse into the life of a movie star, but her life was about far more than Hollywood glamour. Her papers show the compromises that come with being a working actress, the struggles of juggling family and career and the fears of financial insecurity that follow a bitter divorce. But Neal’s ultimate acceptance is also an inspiring lesson. After all the heartaches and pain in her life, she wrote, what remained was love.

“The Dahls entrusted Northwestern with a tremendous gift, the record of their mother’s life,” says Leonard. “It’s our privilege to preserve that gift, to share it with our patrons and to use it to educate future generations of students and scholars.”

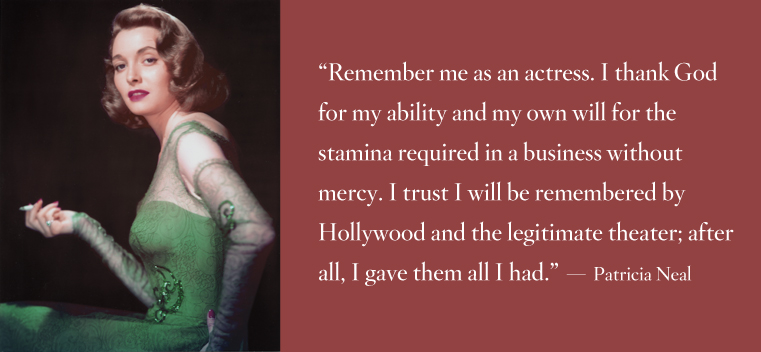

Asked how she would like her mother to be remembered, her daughter Lucy refers to a letter Neal wrote to Larry King in 2002, when he was compiling his book of celebrity eulogies, Remember Me When I’m Gone. “Remember me as an actress,” Neal wrote. “I thank God for my ability and my own will for the stamina required in a business without mercy. I trust I will be remembered by Hollywood and the legitimate theater; after all, I gave them all I had.”

But the letter ends on a more personal note: “I would like to be remembered as someone who put herself out there, someone who reached out to all people with affection, wonder and admiration. … My friends have been as important to me as my immediate family. But it is my darling children who always, always hold my heart. … My mothering was sadly and viciously killed by strokes, which I have often thought should have taken me because I was denied the privilege and joy of nurturing my nippers. But they must know they were always loved unconditionally.”

Neal’s children hope their donation will help keep Patricia Neal’s legacy alive. But don’t look for that letter to Larry King among the boxes at Northwestern. “It is something we chose to keep and treasure ourselves,” says Lucy.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email