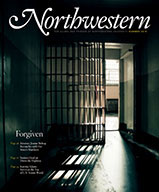

Forgiven

Barbara Mahany ’82 MS is a freelance journalist and the author of Slowing Time: Seeing the Sacred Outside Your Kitchen Door (Abingdon Press, 2014).

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

Public defender Jeanne Bishop believe that criminals can be redeemed, rehabilitated and forgiven — even her sister’s murderer.

Jeanne Bishop in early-morning mode moves with the speed and the purpose most of us could only wish for. And only if fueled on a tank or two of high-octane. Doesn’t take long — nor too many double-time strides — to realize this is Bishop’s default setting.

It’s minutes past 9 in Room 245 of the Second Municipal District Courthouse, the northern outpost of the Cook County Circuit Court, in the Chicago suburb of Skokie, where for the last 14 years Bishop ’81, ’84 JD has worked as a Cook County assistant public defender. (In the 11 years before that she was posted at several of the county’s branch courts in Chicago, including the criminal courts at 26th and California and the Juvenile Court Building at 1100 S. Hamilton.)

She’s among the first to trickle in among the rows of government-issue desks, where all day long the accused, the paroled and assorted hangers-on will line up, take a number, hope for a break — or maybe just someone who’ll look up and listen.

The truth is, Bishop doesn’t so much trickle in; she darts. Down one aisle, she pauses long enough at a waist-high filing cabinet to pull a baguette and a stick of unsalted butter from her faux crocodile satchel. She lays it unceremoniously on a brown paper bag. “Might be all the lunch we get today,” she says, minus any hint of “poor me.”

Then, she’s down another aisle, around a corner and ducking into the three-desk office — no bigger than a coatroom, really — she shares with two colleagues and an intern. On the wall beside her desk hangs a glossy poster with the word “Innocent” spelled out in white-on-black text, and perched atop her bookshelf, a charcoal etching, the face of a young and beautiful woman.

Nancy Bishop Langert in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1990, shortly before she died.

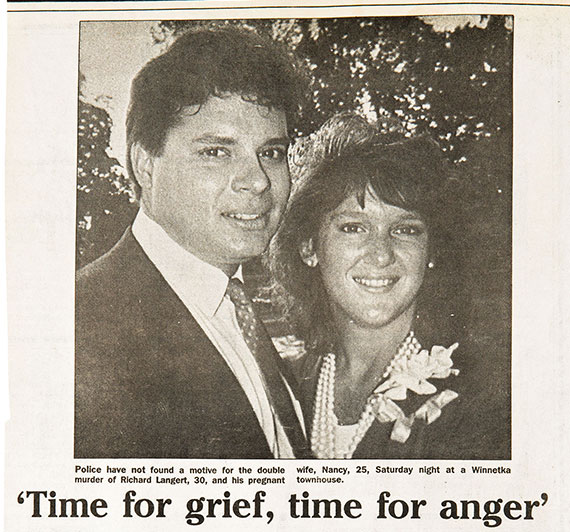

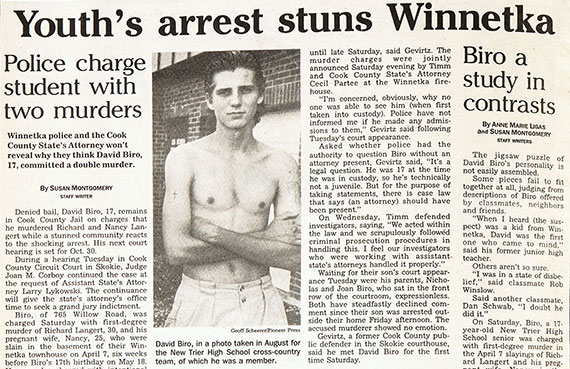

“That’s Nancy,” she says of her kid sister, Nancy Bishop Langert, who was murdered, along with Langert’s husband, Richard, and their unborn child, on April 7, 1990, in the basement of their Winnetka, Ill., townhouse after a 16-year-old junior at New Trier High School, a teenager with a thing for trouble and guns — specifically, a stolen .357 Magnum — broke in on the eve of Palm Sunday.

The teen, dressed all in black, wearing gloves, toting handcuffs and the loaded revolver, used a glass cutter to make his way quietly in through a back sliding door. He’d picked the townhouse, he would later let on, only because it had an unlocked back gate, and that would make for unhindered escape. He waited in the shadows for the couple’s return, then ordered them down the stairs, where he shot Richard in the back of the head and pregnant Nancy in the side and the belly, and left all three to die. In her own blood, Nancy would draw a heart and a “U” on the cold cement floor, next to her husband’s slumped-over body, as she lay dying.

From the moment that blood-scrawled final message was discovered, Bishop believed it was her sister’s undying plea: Live a life of love.

And it is Nancy, who was 25 when she died, to whom Bishop, five years her elder and now 56, has dedicated her life’s work. That dedication plays out in Bishop’s day-to-day dealings with defendants and, far beyond any courtroom, as one of the clearest and most compelling voices in the national conversation calling for juvenile justice reform, abolition of the death penalty and a rare strand of forgiveness and mercy that demands not merely words but action — in her case, face-to-face encounters with her sister’s killer.

Now she’s published her story — a plotline of reconciliation, remorse and redemption that led her through years of refusing to even say aloud her sister’s killer’s name, to visiting him in prison every couple months — in a book titled Change of Heart: Justice, Mercy and Making Peace with My Sister’s Killer (Westminster John Knox Press, 2015), and it’s a story that is riveting readers.

As best-selling author John Grisham has said, “Change of Heart is a tragic story of senseless violence, horrific loss and, in the end, forgiveness that is astonishing. I kept asking myself, ‘As a Christian, could I be as strong and merciful as Jeanne Bishop?’ I have my doubts.”

At Court

At the start of this particular workweek at the Skokie courthouse, Bishop taps out an email or two, grabs a stack of files, makes copies of felony charges filed over the long weekend, and she’s off. Half a plastic cup of orange juice in hand, her boot heels clicking along the tile hallways, she’s speed walking to courtrooms 108 and 209, the two chambers of justice where this day she’ll be the public defender juggling arraignments, warrants, plea bargains and a motley band of probation violators.

She barely sips the juice before unspooling the thoughts that have animated her morning, a stream of consciousness that signals how deeply she practices the compassion, the tender mercy, she preaches.

“What I’m thinking about is how this morning I had a hot shower, I had a nice breakfast with food I picked out. I got dressed in clothes that I picked out. I had a nice drive here. These guys [the defendants she would meet any minute in the lockup outside the courtroom] woke up in a place that’s noisy and cold, under a thin blanket. They’re wearing clothes they didn’t pick. They haven’t eaten, probably won’t eat today. They literally have numbers written in magic marker on their arm, their left forearm, and that’s how they’re called, by number not name; no one calls them Mr. So-and-So. The lockup is noisy, smelly, crowded. They might not get a seat, so they’ll be standing all day. They had to take a long bus ride, in the dark before it was light out, to get here from 26th and California [the Cook County Jail]. So if they’re testy, they might have a whole lot of reasons. I just try to be as kind and respectful as I’d want someone to be to me.”

And, by all accounts, including a long day loping beside her in court, she is. She starts every exchange with every new client with an extended hand, an engaged look on her face and a heartfelt, “I’m Ms. Bishop. I’m your public defender.”

The low murmur of jurisprudence, at least as it’s played out in the green-carpeted box of this courtroom, with row after row of blond-wood benches, is not always one of such decorum. Even with steely-eyed bailiffs barking out reprimands and warnings, whispers give way to long strings of expletives among those who wait hours in the courtroom’s straight-backed pews. One probationer leaps up when told not to, two nearly get in a fight. And through all of it, Bishop, who is tall and rail thin, moves with the grace of a dancer, or maybe a swan.

She starts every exchange with every new client with an extended hand, an engaged look on her face and a heartfelt, “I’m Ms. Bishop. I’m your public defender.”

By the time the day’s last case is called, Bishop will have stepped to the bench on behalf of clients charged with a litany of felonies: credit card fraud, DUI, driving with a suspended or revoked license, theft while on probation for burglary. Some got stepped-up probation, one was put away — a year in prison — for a second such offense. Except for the rattling of handcuffs and the ka-chink, ka-chink of court files being date-stamped, it’s all a drama declaimed in whispers and dry legalese.

But it was in the waning hours of that day, sitting down over a bowl of tomato basil soup at an Evanston café, that Bishop lay open the truths and the struggles and triumphs that have come since the heart-shattering Palm Sunday a quarter-century ago, when she was pulled from the choir at Chicago’s Fourth Presbyterian Church to take a call in the rector’s office. There she heard her father’s voice choke out the words: “Nancy and Richard have been killed.”

At a café table tucked off to the side, Bishop’s words and her story tumbled in sharp relief to the quotidian clatter all around.

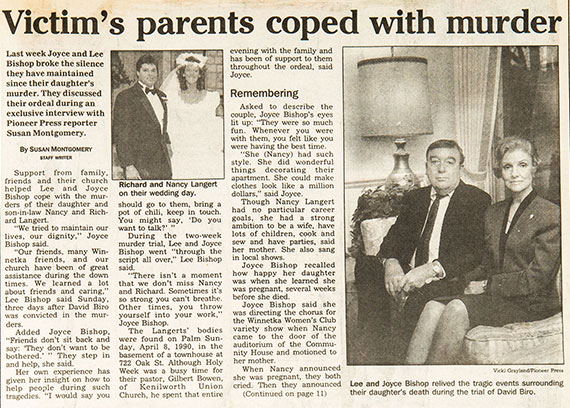

She’s unflinching as she bares her own chafings and the rift, now mended, that her evolving belief had caused in her family — between her and her mother and her surviving sister, Jennifer, who do not buy into Bishop’s commitment to sitting down across from David Biro, her kid sister’s killer, and allowing the seeds of true forgiveness and remorse and redemption to flourish.

In the 25 years since the killings, Bishop has moved from one side of the juvenile justice debate to the other. Even in the early wake of the murders, she and her sister Jennifer had been activists in abolishing the death penalty. But they’d stood firm in their belief that juveniles could be sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. In fact, Bishop had lobbied the Illinois legislature to stop a bill that would have abolished juvenile life sentences. And she had long been a voice insisting that Biro, and others like him, should be locked away forever, even if they had been forgiven by the victims or their families.

Her about-face was not sudden. It came in slow-paced, soul-searching interludes. One of those was a picnic in the summer of 2011 when her two boys, now 15 and 11, were talking with Bishop about pure hearts and the golden rule, and her younger son asked, “What about the person who killed Aunt Nancy?” And her older son, then 11, followed with: “We can’t love what he did, but we have to love him, because God made him for a purpose.”

Another interlude came a year and a half later, when, during a conversation about a possible resentencing hearing for Biro, Bishop told her partner on a death penalty project, a law professor and ex-prosecutor, that she didn’t know if she could support her sister’s killer’s release. “He’s still remorseless,” she insisted. “How do you know that?” the ex-prosecutor replied, leaning across the table. “You don’t know that. You’ve never even talked to him.”

It was those few pointed questions — those of her children and that of the ex-prosecutor, a longtime ally in the movement to abolish the death penalty — that shook the ground on which Bishop had so solidly stood.

First Steps to Forgiveness

So when Bishop talks of her hard-won change of heart and how it all flows from her unwavering faith in a Jesus who uttered the words “Father, forgive them” as he hung on a cross, you can’t help but realize she’s made of rare stuff and her brand of mercy and justice is one worth listening to closely — no matter your personal stance on religion.

“Jeanne shows us that we don’t know what any of us is capable of,” says Bernardine Dohrn, retired associate clinical professor of law and the founding director of Northwestern’s Children and Family Justice Center.

Despite years on opposing sides of the juvenile sentencing debate and countless “headache sessions,” in which Dohrn and Bishop, an adjunct professor in the law school’s trial advocacy program since 1996, argued and counter-argued over long, hard lunches, the two have always been close. Bishop calls Dohrn, a self-proclaimed atheist, “one of my saints.”

“The stories we tell ourselves, that some people are monsters and the rest of us are fully human, are obviously not true,” says Dohrn. “In Illinois everybody should know that. We have had 20 people on death row in Illinois who became fully exonerated between 1987 and 2009. We don’t just mean they got released, they were fully exonerated; they were wrongfully convicted. Systems fail, and the criminal justice system fails often.

“Jeanne’s ability to see in somebody who is the most loathed the possibility, not the realization, but the possibility of becoming their best fully human self is astonishing. She challenges all of us to not stay in our little safety zone of who’s allowed to have the status of human error. She challenges us to really think about that.

“When I taught at Northwestern,” Dohrn continues, “the thing that made law students most rethink their assumptions was going to interview a prisoner in the Illinois prison system, and not just taking a tour, but actually going to interview somebody. It shocked students to their core. It opened their eyes. It made them realize that serious crimes could be committed by people who can grow into their full humanity. You have to be able to see the possibility of development and redemption.”

Bishop’s capacity to see both, to bridge the abyss between victims’ loss and defendants’ chance for redemption, does not escape Steve Drizin ’86 JD, assistant dean of Northwestern’s Bluhm Legal Clinic: “I can tell you that her voice stands out in a crowd because she speaks to the ‘better angels of our nature.’ It is a voice rooted in her faith, which asks for compassion, not condemnation; forgiveness, not damnation; and mercy, not cruelty. Too often, in the criminal justice system, we hear the shrill cry of victims for retribution. Jeanne reminds us that not all victims speak with one voice.”

Ever since she can remember — all the way back to the starry night in the Texas countryside, when she was a first-time camper, looking into the heavens and noticing how “vast and majestic God is” — Bishop’s faith has illuminated her way.

It’s why she became a Cook County public defender, leaving behind a plum post at a top-notch Chicago law firm. And why, along with her sister Jennifer, she worked ceaselessly against the death penalty and spoke eloquently for gun violence prevention, exoneration of the innocent and the role of faith in the debate over executions. It was why, in the long shadow of the Langert murders, she forgave Biro.

Moving Beyond Forgiveness

But the journey she’s taken ultimately reached a crossroad: Her brand of believing, she came to realize, demanded more than mere forgiveness. It begged reconciliation. That’s on the far side of forgiveness. And it requires two people. Two people sitting down and poring over the landscape that stretches between them, the landscape that in this case brought Biro and Bishop together on that awful April Saturday of 1990.

At first, the notion of reconciliation sickened her — and made her furious. Wasn’t it enough — the forgiveness, the finally letting spill from her lips the name she’d long sworn she never would utter? (Not wanting David Biro to gain the infamy of killers John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer and Timothy McVeigh, whose names are remembered and whose victims’ are not, she’d only ever called him “the killer.”)

“Sometimes what faith tells you to do sounds impossible, almost irrational,” Bishop has said. “Jesus said, ‘Love your enemies.’ ”

So, after tucking her two boys into bed on the last Sunday night in September of 2012, Bishop crept down the stairs of her darkened house, turned on a desk lamp and sat down to type a letter to Biro. “I scarcely know how to write this,” she began, but then typed her way through page after page. Her last line was this: “I invite you to talk with me. If you want that, let me know, and I will come see you.”

Weeks later, at the courthouse, a large manila envelope was stuffed in her mail slot. She thought nothing of the return address with the name of the prison — public defenders often get mail from clients in prison. But then, the next word, the word after “Pontiac,” it was the one for so many years she’d refused to say aloud: “Biro.”

The Prison Visits

On the first Sunday in March 2013, Bishop drove the 155 miles to Pontiac Correctional Center, the rising sun spilling gold across snowy fields dotted with stiff cornstalks.

There, she pulled into the parking lot of the maximum-security prison, the gravel crunching under her tires. And she made her way through the labyrinth that is prison entry, and waited in the hallway for the buzz of the heavy steel door, and for the tattooed, 6-foot-5 Biro to step through and reach out a hand. Moments later, under the unbroken gaze of a guard, he would sit down across from her — a thick wall of glass dividing the air between them in the numbered cubicle to which they’d been assigned and escorted.

The visits — the long conversations, the questions, the insistence on truth-telling — continue to this day. Every couple of months.

“He’s answered a lot of those questions that I’ve had, and I’m so grateful for those answers,” says Bishop. “I’ve been able to say a lot of things to him that I wanted him to hear as part of a larger victim impact statement — that it wasn’t just Nancy and Richard that he hurt, but that it was my mother, my father, my sister, my children. Everybody who worked with Nancy and Richard, who went to school with them, who loved them. The evidence technicians who had to process the crime scene that he left behind. His family. There are all these ripples that go out and out.”

She stops for one quick gulp of air. Then, she dives in again: “Obviously, I couldn’t do this all in one visit. It’s too much to bear. We’d be exhausted. We had to space it all out over time.”

In the beginning, she says, conversation zeroed in on the horrors of April 7, the Saturday evening 23 years before, when the Bishops had gathered as a family over pasta and wine at a North Side eatery to celebrate Nancy’s pregnancy, the last time any of them would see her alive.

In the two years since the first prison visit, Bishop says the conversations have unspooled toward “thoughts about God, about faith. Whatever he’s reading or thinking about.”

And what evidence — if any — has she culled, what sense that something has shifted, that the change of heart is not only hers?

“The only way I can describe this,” she begins, “you know when you’re outside on a sunny day and the pavement’s bright and your skin is bright, the colors are bright? And then, when a cloud passes in front of the sun, everything darkens a shade? That’s what happens to his face when he hears something that I know has affected him. It’s just like that. Just recently, I had said something about my mother or sister, and he said, ‘The more I get to know about your family, the worse I feel about what I did.’

“And I thought that was amazing. And it makes so much sense — because if you’re hurting a stranger, and you don’t see the collateral consequences of the harm that you did, you don’t feel bad about it, right? But if you learn how good she was, how kind, how beloved she was, how funny, how life-giving, then you feel bad. You feel bad for the people who lost her in their lives.”

Bishop looks straight in your eyes when she says this. It’s as if she’s just laid out the most logical truth that ever there was. She makes it sound so obvious, so inarguable. As if everyone in the world should see it so clearly.

No Throwaway People

Shobha Mahadev, project director of the Illinois Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Children and clinical assistant professor of law at the Children and Family Justice Center, says that’s what makes Bishop’s voice “absolutely critical to the conversation,” the one centered on the belief that “no person is a throwaway person, no child is a throwaway child.”

“The power in what [Jeanne] has to say, it’s all about forgiveness,” says Mahadev ’99 JD. “We all have to find our own journey when a terrible thing has happened to us. She is a lesson in how that can be an extraordinary journey, and how you can come out of it with power and grace. Jeanne’s lesson is: Redemption is possible. What she tells us is that not all victims are asking that this person be put in prison forever and they never see the light of day.”

In her book, Bishop writes: “I’d always thought that the only thing big enough to pay for the life of my sister was a life sentence for the killer. Now I understood: The only thing big enough to equal the loss of her life was for him to be found.”

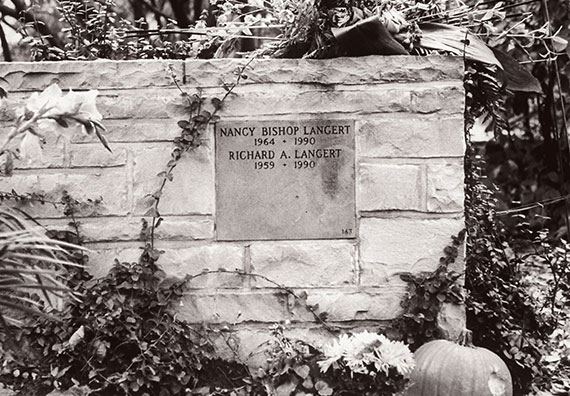

A plaque in the courtyard of Kenilworth Union Church, where Richard and Nancy Langert’s cremated remains are buried. Photo by William Franklin McMahon/Contributor.

As she puts down her soupspoon and readies to head back to the courthouse for a day-ending round of filing and photocopying, Bishop offers her closing argument:

“Here’s the message: People change. I changed. Look at me. My heart changed. On something I never thought it would. So why not him? That’s where my faith comes in. Looking at him, I asked, ‘Can God do the impossible, really? What if he’s a sociopath? I heard they can never get better. Can God change the heart of this person?’ ”

She pauses, as if to suggest that yes, of course, hearts can be changed.

“There’s no way we can justify the heartless, lock-’em-up-forever-no-matter-how-much-they-change sentences.

“We are throwing away human lives, we’re causing misery for them and their families. We need a system that will take into account redemption and restoration, and not just punishment and retribution. I want this to be a voice in the conversation.

“The last thing is this: The argument always is that victims need finality, legal finality. My message is there are two paths to finality. The path of lock-’em-up, throw-away-the-key, let-’em-rot-and-die. Or the finality of ‘We have rehabilitated this person, and they’re no longer a threat, so after an appropriate amount of time commensurate with the crime, they can walk out, they’ve come home, we’re done with the case.’ And that’s what I’m advocating.”

And that’s the truth at the change of the heart.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email