Say What?

Contact the Center for Audiology, Speech, Language, and Learning.

Stephanie Russell is editor of Northwestern magazine.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

If you’re missing part of the conversation, Northwestern audiologists can help you cope with hearing loss and plug you into the latest research on the best treatments and devices to keep you tuned in to life.

Fritz Bader has been hard on his hearing.

He grew up on a farm near Covington, Ohio. During high school summers when there was a lull between planting and harvesting he worked as a machinist for a local contractor, running a jackhammer, often two weeks at a time — with no hearing protection.

In 1962 Bader was drafted by the U.S. Army. He trained as a sharpshooter and then taught escape and evasion techniques at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. He fired weapons throughout his service — and never wore earplugs.

Following his Army stint, Bader moved to Cincinnati and went into furniture sales. A fan of rock music, he was one of the first on his block to get a state-of-the-art stereo system. “We had some of the first 901 speakers that Bose ever made,” recalls Bader, 75. “I bought four of them and wired them in parallel and had an 1,800-watt amplifier — it was loud enough to melt paint at 60 paces.”

It was while on business in China, where he was having custom furniture made, that he realized he had a problem. “I was only hearing every fifth word. So it’s been a gradual overtaxing of my hearing.”

A master lip reader for years, Bader ignored the advice of his wife and children to get a hearing test. Why? “Call it pride. I didn’t need hearing aids.”

But then his family went from asking to insisting.

Fritz Bader wears hearing protection when he helps his son build custom metal furniture at Bader Art Metal & Fabrication in Skokie, Ill.

Finally in 2010, more than 30 years after he first noticed his hearing loss, Bader sought help at Northwestern’s audiology clinic. A patient of audiologist and clinician Pamela Souza, Bader got his first hearing aids in 2013. Today he works with his son Austin, who runs a custom metal art and furniture business. And nowadays he wears a protective hearing headset when they’re cutting, welding and polishing metal.

Bader was perhaps more resistant than many people with hearing problems. Most people with hearing loss wait about seven to 10 years before seeking help, say audiologists. But the longer you wait, the harder it gets for your brain to process sounds through a hearing aid.

It’s estimated that 36 to 40 million people have significant hearing loss in the United States, and that number will rise to 50 million by the next decade. Worldwide, between 350 and 400 million people suffer from significant hearing loss.

New Home for the Audiology Clinic

Northwestern, considered the birthplace of audiology, has a rich history of research on the physiology of hearing in its communication sciences and disorders department. The department has been conducting cutting-edge research on hearing since 1928 and providing clinical care for more than 60 years, while also training future doctors of audiology.

Last January the audiology clinic moved to a new state-of-the-art building in the North Parking Garage, where it is now part of the Center for Audiology, Speech, Language and Learning. The audiology clinic offers comprehensive hearing evaluations, hearing aids, and communication and hearing enhancement classes that help people cope with hearing loss and develop strategies to listen better in our noise-saturated world. It also offers a virtual sound room — one of the first in North America — where audiologists can create the sounds of the real world, such as a concert hall or a busy restaurant, and fit a hearing aid on a patient in that environment.

What makes Northwestern rather unique among audiology research centers is having a clinic next door. “Much of our research — early detection of hearing loss, the interaction between general cognitive processes and hearing loss, the brain’s response to speech and noise — is finding its way into our clinic faster than it ever has before,” says Sumit Dhar, chair of the Roxelyn and Richard Pepper Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders in the School of Communication. “There are very few places where there’s such a close link. We’re doing the best research in the world on this topic, and across the street we’re implementing that research in caring for folks who walk in the door of our clinic.”

Our Hearing Isn’t What It Used to Be

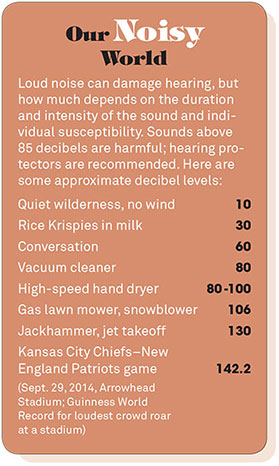

Noise assaults our hearing night and day. From leaf blowers and hair dryers to today’s stylish and sleek but loud restaurants, the decibel level of the world around us is skyrocketing. Adding to the onslaught is the proliferation of digital devices with earphones that we insert deep into our ears and headphones that block out all other noise as we blast music.

While industrial workplace noise exposure is subject to federal regulation, recreational noise exposure is virtually unregulated. “You can fill a stadium with 100,000 people at a football game and expose them for two hours to sound levels reaching 142 decibels,” says neurobiologist Jonathan Siegel, who studies early detection of hearing loss. “People report the sensation is painful and ear splitting. And people wonder whether this is damaging or not?”

While industrial workplace noise exposure is subject to federal regulation, recreational noise exposure is virtually unregulated. “You can fill a stadium with 100,000 people at a football game and expose them for two hours to sound levels reaching 142 decibels,” says neurobiologist Jonathan Siegel, who studies early detection of hearing loss. “People report the sensation is painful and ear splitting. And people wonder whether this is damaging or not?”

But our hearing isn’t what it used to be. “In the 1950s and ’60s audiologists tested the hearing of people in an African tribe where noise pollution was nonexistent, the diet was very different [from Westerners’ diet], and the aging trajectories were as different as night and day,” says Dhar. The result? “A 70-year-old ear in Africa looked like a 30-year-old ear in the United States in that comparative work. It was quite dramatic.”

Audiologists and researchers are uncertain about what is purely a process of aging and what is the result of abuse, because researchers can’t run trials on humans. But “what we do know is that much of the damage that we consider age-related hearing loss may be preventable or modifiable,” explains Dhar. “So researchers have focused on these factors: noise, diet and cardiovascular health.” They’ve found that anything that relates to cholesterol and impedes the blood supply to the ear can be detrimental to hearing.

Hearing Loss: How It Starts

“Everybody mumbles” — that’s one of the first things that patients complain about when they go to the audiology clinic. “If a person is having more trouble with background noise than other people, that’s a pretty good sign they have hearing loss,” says audiologist Cindy Erdos.

Ringing in the ears — tinnitus — can indicate damage to the hair cells in the inner ear. Frequently when you’re exposed to extremely loud sounds, let’s say at a rock concert, you’ll get a temporary impairment of the inner ear function that seems to recover over time — what audiologists call a temporary threshold shift. But there are incidents when just one episode of tinnitus can result in permanent hearing loss, says Erdos. Some people have tender ears, and that’s all it takes.

“We don’t really have a good enough sense of what damage to the inner ear can be caused by loud sound, even though it’s been known for some time that it happens,” explains Siegel, an associate professor in the communication sciences and disorders department and an associate professor of neurobiology. “The challenge is to detect it at the earliest state so you can take some remediation course, which most frequently just involves counseling people on how to protect their hearing, because we don’t have a way to reverse the damage — yet.”

Siegel and Dhar collaborate on measuring peripheral hearing damage using sounds called otoacoustic emissions that are emitted by healthy ears and that are related to how the inner ear sensory cells function. “These cells are among the most sensitive to noxious things that cause hearing loss,” explains Siegel. One offshoot of their work is a partnership with Etymotic Research Inc. to develop a new hearing test instrument specifically designed to measure otoacoustic emissions with much better stimulus control than ever before.

Siegel and Dhar collaborate on measuring peripheral hearing damage using sounds called otoacoustic emissions that are emitted by healthy ears and that are related to how the inner ear sensory cells function. “These cells are among the most sensitive to noxious things that cause hearing loss,” explains Siegel. One offshoot of their work is a partnership with Etymotic Research Inc. to develop a new hearing test instrument specifically designed to measure otoacoustic emissions with much better stimulus control than ever before.

Some of Siegel’s current research focuses on students who participate in two favorite pastimes on campus: Dance Marathon and Wildcat basketball games. “What we’ve found is that at some of the basketball games that are especially competitive the sound levels can be considerably louder than at Dance Marathon,” he says. “But Dance Marathon lasts for 30 hours.”

However, a study of six students who participated in Dance Marathon last year indicated that none of them showed any evidence of threshold changes or otoacoustic emissions after long exposures to 90-plus decibels of sound for 30 hours.

“This was very surprising,” says Siegel. “But you could see from the dosimeter records over a period of hours that the sound levels actually declined over time, and the levels weren’t as high as you routinely get in a nightclub or at sporting events. Somebody was in control of the volume level.

“But it could also be that with people who are young and healthy enough to participate in Dance Marathon, the exercise itself might be protective.”

Hearing and the Brain

One of the most compelling reasons to treat hearing loss early is that your brain changes with hearing loss.

“There’s an association between lower cognitive ability late in life and more hearing loss, based on hearing data research,” explains Pamela Souza. “That doesn’t necessarily mean they get dementia, but people who have more hearing loss take a bigger hit on their cognitive ability.”

People only have so much cognitive ability to allocate to what they’re doing at a given time. If you have more hearing loss, more of that cognitive capacity is being allocated to trying to listen and make out and remember what people are saying. Audiologists call this “working memory.” So working memory is processing and storage — it’s continually active as you’re listening to someone.

“We’ve found that working memory helps predict how well a person will communicate in a difficult listening situation,” says Souza. “There’s a point where it’s not just your ears — it’s your brain.”

•••

Hearing aids are amplifiers that can be adjusted for whatever pitch range and level is a difficulty for that person. They are based on the pure-tone audiogram, the hearing test in which you listen to sounds and tones of different pitches, and it determines how soft you can hear the sound. “You can have two people with identical audiograms who are equally sensitive to tones across pitches, but they have very different communication abilities,” says Souza. “One may understand speech quite well; the other may not. If you put the same hearing aid on both, one may respond very well to the hearing aid, and the other may not, even though on paper, based on that one basic test, they look pretty much the same.

“The pure-tone audiogram is a good starting point, but it’s only capturing a very small amount of all the things that go into hearing a conversation,” adds Souza. “It’s a simplistic test.

“We’ve been interested in testing beyond that, so we can characterize the listening abilities of an individual in a more detailed way that will help us make more targeted choices in what the hearing aid and signal processing [a system that uses filtering and amplification to improve speech intelligibility] will do. We have found that the hearing aid processing that you choose should be customized not just to the ear but to the brain, to a person’s working memory.”

Going Digital

In the past decade hearing aids have gone from analog devices with limited control to digital devices that contain sophisticated computer chips. Hearing aids today can be fine-tuned to match the configuration of your hearing loss much more precisely than previously possible.

Another big jump has been in directional microphones. Hearing aids now have multiple microphones instead of just one. Fritz Bader has four different settings on his hearing aid: normal, telephone, background noise–deafening and off. “Give me a book, and I just yank out my hearing aids,” says Bader. But when he’s in a noisy restaurant, for example, he can switch to background noise–deafening mode so the hearing aid focuses on what or who is in front of him rather than what’s all around him.

A more recent innovation has been the marriage of smartphones with hearing aids and amplifiers. “Most people don’t like to get hearing aids because they say they make them feel old,” says Diane Novak, audiology clinic manager. “So if you can tie a hearing aid to technology that everyone else is using, you don’t seem so different. It becomes more of a personal item when you’re able to stream music into your hearing aid or you’re able to talk on your phone through it. This has helped a lot with overcoming the stigma of wearing hearing aids.”

“The ability to personalize hearing aids — this is the next wave,” says Andy Sabin ’12 PhD who, as a doctoral student, created a free app called Ear Machine that lets people use their Apple iOS devices as an amplifier. The sounds are picked up by the microphone on the phone or on the headphones and then sent out to the speakers or earbuds in your ears and then amplified.

From looking at usage patterns of the Ear Machine app (developed with help from INVO, the University’s Innovation and New Ventures Office), Sabin has noticed that the usage tracks very closely to TV ratings. The maximum use time is right at the peak of prime-time television.

“We know that one of the things that inspires people to get hearing aids is a fight with their spouse about the appropriate TV volume level,” says Sabin. “It seems that people are often using Ear Machine so that the person who needs it to be louder can put some earbuds in their ear and turn up the volume to the level they want, while the person who wants it quieter can set the television volume where they want it.”

Another assistive hearing device that’s been around for years but is only recently gaining popularity in the United States is the hearing loop, a wire that circles a room and is connected to a sound system. Through a telecoil that is attached to a hearing aid or cochlear implant, the sound is transmitted electromagnetically, so the listener is connected directly to the sound source while most of the background noise is eliminated. More and more theaters and public places are looped. It can be a transformative device for people with hearing loss. “I have a patient in his mid-50s who’s had hereditary hearing loss his whole life who just recently got hearing aids,” says audiologist Erdos. “Then he got a telecoil, and when he went into an environment that was looped, he was amazed. He and his wife have season tickets at several Chicago-area theaters. Now they ask if they’re looped before they get their tickets.”

Dining Din

In Zagat’s first-ever dining trends survey, published in 2014, diners’ number one complaint was restaurant noise, 3 percentage points ahead of poor service. That comes as no surprise to audiologists. “The first aspect of hearing that degrades is understanding speech in background noise, especially when the background noise also happens to be speech,” says Dhar. “That’s exactly the scenario at a lot of restaurants — no absorptive surfaces and lots of reverberation so that every sound produced lingers in the air. That then adds to the din, and the din happens to be not only noise, but also speech, so it’s very confusing to the brain.”

While a hearing aid might help people with hearing loss cope with some dining situations, hardware isn’t the only or best answer.

“I figured you could give people a tool so they can factor sound levels into their decision on where to go on a Saturday night,” says Andy Sabin.

So he created an app for that — VenueDB. It lets people make sound-level measurements and then uses GPS to connect to a venue database provided by Foursquare, so people can confirm which restaurant or venue they’re at. Once they make the measurement on VenueDB, they get a decibel reading, and if they click on it, it brings up a detail screen that computes the recommended exposure limit. “That tells you how long you can be in that environment without causing ear damage,” explains Sabin.

The measurements are stored on Ear Machine’s servers. Eventually the app could generate a huge database that people could search to determine the best time to go to a restaurant to avoid noise. One user told Sabin, “As a patron I love this app; as a restaurant owner I hate it.”

Aural Rehab

To help people cope with hearing loss and adjust to hearing aids, the clinic offers a five-week aural rehabilitation class that is led by audiology graduate students and University audiologists. The class, which is like a support group, helps people understand their own hearing loss and its impact on their lives — and it gives them strategies to listen and communicate smarter.

“One of the strategies we discussed involves talking with your spouse at home. It is helpful to be in the same room and to arrange your furniture so that you face each other,” explains Marilyn Larson, 79, of Northfield, Ill., who took the class after visiting the clinic during an open house and getting a screening. Larson, who has mild to moderate hearing loss, says that a lot of the advice might seem like common sense. But the strategies are useful, and her husband, Russell Larson ’56, has been supportive, though sometimes “he’ll say something to me from two rooms away,” she says with a laugh. “He just needs a reminder.”

Ulla-Britt Tidstrom, 77, a retired nurse who lives in Chicago, says the class — and her fellow participants — helped her understand that you have to get used to big changes when you first start wearing hearing aids. “Some people get hearing aids and think that right away their hearing is going to be perfect,” says Tidstrom. “What I learned in the class is that you have to be patient.” Before getting her hearing aids, Tidstrom was irritated that she couldn’t hear what friends in her sewing circle were saying. “Now I can hear everything,” she says, “even the gossip.”

•••

While patients at the clinic tend to be in their 70s and older, younger people are seeking help. “I’ve been in audiology 25 years, and in the last five to 10 years I am starting to see younger and younger people, people in their 40s and 50s, who are coming in just as they start to experience hearing loss, and they’re recognizing that it’s affecting their work,” says Erdos.

There have been several studies where researchers have measured how loudly people listen to personal digital devices. “And the consensus seems to be that a very small percentage listens to these devices at harmful levels,” says Dhar.

“Americans are more focused today on living a healthier lifestyle,” he adds. “So the choices we’re making in our 40s and 50s are a positive counterbalance to the abuse we often inflict on our hearing early in life.”

Nonetheless, audiologists suggest that you keep a few key things in mind if you’re missing part of the conversation: identify your hearing loss early, get treatment early and protect your hearing while you can.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email