Musica Libre

Mary Mugica Winter ’75 of Arlington Heights, Ill., recently retired as chair of the English department at the College of Lake County in Grayslake.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Ever wonder about those strange designations we use throughout Northwestern to identify alumni of the various schools of the University? See the complete list.

Find Us on Social Media

Cuban rhythms keep a woman connected to her homeland — and the world around her.

It was my mother who first imagined I could go to Northwestern.

We had just emigrated from Cuba and were living in a tiny two-bedroom apartment on Foster Street, above Great Expectations bookstore and right next to the “L.” During an after-dinner walk, my mother, famous for getting lost, had done it again. Instead of finding our way back to the apartment, we ended up on Sheridan Road, just as the Northwestern Homecoming parade was in full swing.

For my mother, this was a lucky coincidence that encompassed three things she loved: parades, schools and wrong turns that turned out right.

Be it an excess of optimism or plain old faith, my mother always believed in happy endings — a remarkable attitude considering that she had just fled the only country she had ever known, penniless, that she was working two jobs and that my father was working three.

So on that fall evening, as the floats drifted by and the band played and the students cheered, my mother did not think it at all odd to turn to me and say, “Mi’ja, I think this is where you will go to university, yes?”

The thing is, I was only 7 at the time. And couldn’t speak English. And throwing up just about every day, before, during and after school, because the third grade was terrifying. College?

But because my mother said Northwestern could happen to me, I believed her, and it did. I learned English. I was awarded scholarships. Through the work-study program I landed a part-time job in the library — perfect for a bookworm like me, and even more important, fostering lifelong friendships with other young women on scholarship. I graduated from Northwestern, feeling forever fortunate that I’d had a chance to join the parade instead of just watching — a happy ending, all because of a wrong turn gone right.

At this point in my mother’s life, her belief in happy endings is sorely testing us both. Call it cognitive impairment or dementia or Alzheimer’s — whatever label doctors apply to her condition these days, the person my mother used to be goes away, a lot. There are good days, when she asks after the grandchildren or tells jokes. But increasingly, most days she is anxious, repeating the same question countless times, looking for people who are long gone, unable to recall the most familiar of events.

As her daughter, I too struggle with what I may have forgotten. Did I remember to tell my mother, when she could take it in, how proud of her I was? Did I remember to thank her for being the very first person who held me close but pushed me forward too?

There is a section in the ancient Mayan story Popol Vuh that reminds me of what my mother is enduring. When the gods made the first persons, the story tells us, their eyes were too sharp. The creations could view what their creators could. Unhappy with that equality, the gods passed their hands swiftly, suddenly, over all human eyes and dimmed the mortal world.

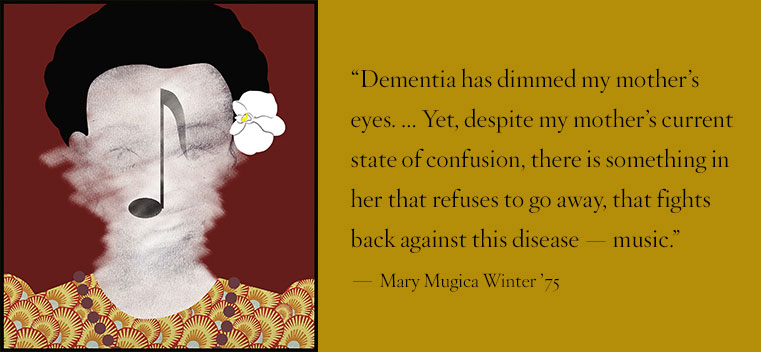

Dementia has dimmed my mother’s eyes. She has lost sight of a great deal of occurrences and achievements in her life: her success in the workplace, her ability to be charming and charismatic in two languages, her travels around the globe.

Yet, despite my mother’s current state of confusion, there is something in her that refuses to go away, that fights back against this disease — music.

My mother was a gifted pianist, inhabiting each and every key as if it were a home that needed her in it. Her specialty was the rhythmic, romantic Cuban bolero. I can be in a restaurant or driving in the car with the Latin station tuned in, and if I hear a few bars of these tunes, I’m transported back to Foster Street, where every weekend my mother was the star attraction. There weren’t many Latinos in Chicago in the ’60s, but my parents managed to befriend every immigrant from Peru or Chile or Mexico or Colombia — and invite them to Saturday music nights. My mother would play the piano, uniting a group of people who were struggling to survive in their new world. For a little while she held us together, giving refuge in the joy of melodies.

The night my mother moved into her memory care unit, I helped her down to dinner. She noticed a piano, dusty and closed, in the corner of the dining room. But it was Saturday night after all, and there were people all around her who needed to be entertained, who needed to make sense of their new world too. She sat down and played, every song in the Cuban songbook — the tunes were impossible to erase.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email