Engaging Art

Related Articles

Elizabeth Canning Blackwell ’90 is a freelance writer in Glenview, Ill.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art has become more than a place to see exhibits — it’s now a driving force for collaboration across campus and beyond.

One evening last spring, an eclectic group of faculty and students gathered at Northwestern for a program on capital punishment. Former prisoners who had been exonerated shared their experiences in a discussion facilitated by the law school’s Center on Wrongful Convictions while the director of an Evanston nonprofit discussed ways to keep at-risk teenagers out of the justice system.

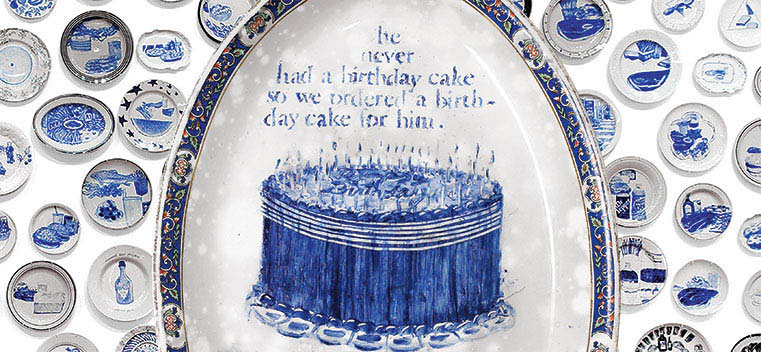

What set this particular gathering apart was where it was held: the Evanston campus’ Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art. Inspired by the exhibit The Last Supper: 600 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates, for which artist Julie Green painted prisoners’ final meal requests on porcelain dishes, the event was just one of the ways museum staff used Green’s art to inspire larger conversations.

The topics raised by the exhibit obviously resonated with the public; the show drew a large, demographically diverse audience from within and outside the University.

“I was deeply impressed,” says Green, a professor of art at Oregon State University. “Since 2000, The Last Supper series has been displayed at 30 museums and galleries in the United States and abroad, and this show had the most extensive outreach to date. No matter what your stance on capital punishment, the exhibition at Northwestern sparked conversation, debate and research.”

That’s exactly what Lisa Corrin, the museum’s Ellen Philips Katz Director, intended. “Visitors felt like they were part of a very timely dialogue,” she says. “Art isn’t separate from the world — it can be a springboard for talking about things that really matter. A museum can provide that safe space for discussion.”

Block director Lisa Corrin, on right, and artist Julie Green at an opening day program for Green’s The Last Supper exhibition at the Block Museum. Photo by Sean Su/Daily Northwestern.

Such programs have transformed the Block into an influential force on campus, an institution whose mission includes not just displaying art but also exploring the issues those artworks raise. By working with a wide range of academic departments and off-campus organizations, the museum looks both outward and inward, welcoming partnerships with other academic institutions while also boosting the visibility of Northwestern’s own collections.

Underlying all its initiatives and programming are the central questions: What does it mean to be a university museum, and how does the Block meet that goal?

Opened in 1980 as the Mary and Leigh Block Gallery (named in honor of noted Chicago art collectors who were major donors to the gallery), the Block raised its on-campus profile in 2000 with the construction of a substantially larger glass-and-limestone building (funded in part by a generous gift from Paul H. Leffmann in honor of his wife, Theo Leffmann). The museum has 5,600 square feet of exhibition space in three galleries; a 150-seat auditorium for lectures and film screenings; and a study room that holds most of the museum’s permanent collection, with strength in photographs, drawings and prints. The Ellen Philips Katz and Howard C. Katz Gallery is reserved primarily for exhibitions conceived and curated by students and classes. “It really demonstrates the ideal of the Block as a laboratory,” says Kathleen Bickford Berzock, the museum’s associate director of curatorial affairs and a widely recognized expert in African art.

But the museum’s reinvention goes far beyond its physical structure. “Lisa Corrin likes to describe the Block as a state of mind,” Berzock says. “Everybody is a potential collaborator, and we want to engage with creative ideas. We’d like to be a bridge between the campus and the world beyond Northwestern, especially the communities surrounding the University.”

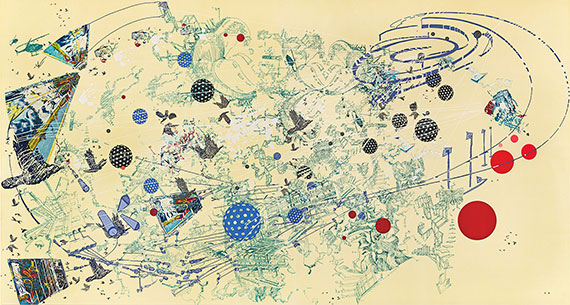

Sarah Sze, Day, 2003, offset lithograph and silkscreen. Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 2012.3b © Sarah Sze. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

That approach has been the centerpiece of Corrin’s leadership since she took charge in 2012. A former director of the Williams College Museum of Art and deputy director of art at the Seattle Art Museum, Corrin was also chief curator at the Serpentine Gallery in London for 14 years. It was Northwestern itself, she says, that drew her to the Block. “A great research university needs an art museum that’s tied to its DNA,” she says. “At Northwestern there’s an emphasis on global education and opportunities to connect the classroom to what’s going on outside.” She was also struck by the expansive curiosity of Northwestern students. “There are so many double majors, because students here want to develop different sides of themselves and see how the dots connect,” she says.

While Corrin and her staff work closely with the departments of art history and art theory and practice, they’re also eager to reach out to other disciplines. “The Block has done a remarkable job fulfilling its mission as a teaching museum,” says Harris Feinsod, an assistant professor of English. “My programming collaborations with the museum are always highlights of the year for me and my students, and the national reputation of Block Cinema has allowed us to screen rare documentaries that wouldn’t have been loaned to us otherwise.”

Corrin likes to describe her vision of the Block as a constellation in the night sky. “There are a lot of shining stars out there in the University,” she says. “We want to connect them not just with us but also with each other, with other major cultural resources in the area and with other universities. People can get siloed in a particular discipline. We’re always looking at how we can seize opportunities to get different people to engage with each other who might not have otherwise met.”

The Block mounts six to 10 exhibits each year, with many of them actively involving students in various ways. Exhibits range from new work by established artists (for instance the recent Geof Oppenheimer: Big Boss and the Ecstasy of Pressures, which included a massive sculpture with cinder block walls and a video sculpture created by the Chicago-based artist) to historical surveys (a show of Iranian cinema posters dating back to the 1960s, donated by Hamid Naficy, Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani Professor in Communication, is scheduled for fall 2016). Each exhibition is considered not only on its merits but also on its potential for how it will connect to teaching and learning, as well as for potential programming partnerships on and off campus. When possible, the artists themselves are brought in for workshops or residencies, and experts are invited to present on topics related to exhibition themes.

Drawing on the museum’s “Northwestern DNA,” some exhibits have been inspired by on-campus resources. The upcoming A Feast of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde, 1960s–1980s, opening Jan. 15, explores the work of the influential performer and advocate for experimental art best known as the “topless cellist” because of her arrest for indecent exposure during a public performance in 1967; many objects featured in the show come from the Charlotte Moorman Archives, housed in Northwestern’s Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. The museum, in partnership with the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, also hosted internationally acclaimed French-Algerian artist Kader Attia to study photographs, documents and other objects in the library’s collection.

Charlotte Moorman performs Nam June Paik’s Concerto for TV Cello and Videotapes, New York, 1971. © Takahiko Iimura.

The Block’s own collection sparked one of the museum’s most well-received recent exhibits, The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929–1940. John Murphy, a doctoral candidate in art history, and Jill Bugajski ’14 PhD were intrigued by pieces in the collection created by social activist artists who were members of the John Reed Club in the 1930s. (The club took its name from the American journalist who wrote firsthand accounts of the Russian Revolution.) What began in 2014 as a small project featuring only works from the Block collection turned into a full-fledged traveling exhibition that examined the influence of artists on the so-called “Red Decade.”

At New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, The Left Front was reviewed and pronounced “fascinating” by art critic Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker. Public recognition from such an influential art world figure was “a real shot in the arm for the whole staff,” says Corrin. “Our students are our legacy, and it was wonderful to see two graduate students singled out for their original research.”

Lynn Gumpert, director of the Grey Gallery, credits Corrin and her staff with raising the Block’s national and international profile. “The Left Front generated an amazing response, and it’s exactly the type of collaboration we look to foster,” she says. She remembers visiting Northwestern when the Block sponsored a re-creation of Allan Kaprow’s Fluids, a blend of sculpture and performance art in which 375 chunks of ice were piled into a massive structure and then left to melt. “I was amazed by that installation because physically, it’s a very challenging piece to exhibit,” she says. “I admire that fearlessness, that willingness to go outside the box.”

“A lot of what we’re doing is meant to engage with what’s at the cutting edge of curatorial practice,” says Susannah Bielak, the Block’s director of engagement and curator of public practice, who has been instrumental in building projects, programs and relationships with groups both on and off campus. “There are a lot of larger questions being asked about museums and their relevancy, such as why do museums matter?”

One of the most prominent ethical dilemmas facing museums today is provenance. How did a particular piece end up here? (The centuries-long controversy over the British Museum’s Elgin marbles, which were stripped from the Parthenon in Athens, is perhaps the most famous example.)

The Block faced this debate head-on in two complementary exhibits that debuted in early 2015, Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and Its Legacies and Collecting Culture: Himalaya Through the Lens. The first presented sacred Buddhist objects as artworks worthy of aesthetic admiration; the second examined the sometimes questionable ways those objects came into Western collections.

In the show’s introductory text, curator Rob Linrothe, an associate professor of art history at Northwestern, challenged visitors to consider what is lost and what is gained in collecting across cultures. Speakers during the show’s run included a Chicago photographer who has traveled in Kashmir; a historian from New Delhi who spoke about his family’s history in the Western Himalayas; and an anthropology professor from the University of Michigan who discussed how a prominent collector of Himalayan art in the 1930s used unscrupulous methods to get what he wanted.

Collecting Paradise went on to the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, and a review in the New York Times applauded the Block for taking on this “momentous” issue.

The works of art featured in the exhibition were of the highest caliber. “It was the kind of show you could have seen at any great museum,” says Corrin proudly. The loans were masterpieces lent by major institutions with important holdings in Himalayan art.

Corrin has recruited a leadership team that shares her ambitious vision, and she’s quick to point out that the Block’s increasing prominence in the art world is a group achievement. “I love to be in a room full of people who are smarter than I am and who think differently,” says Corrin. “By discussing new ways of doing things and bringing fresh perspectives to the table, we’re modeling the kind of experiences we want our students to have.”

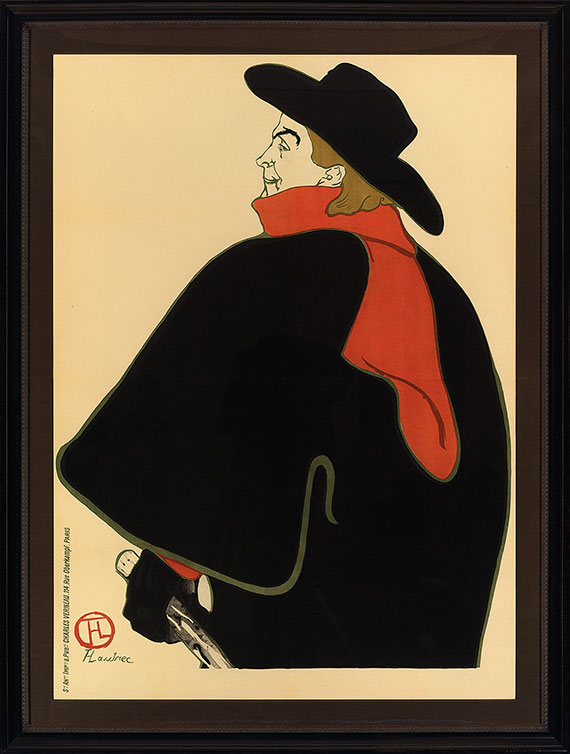

Art history professor Hollis Clayson says the Block has given her students a chance to experience practical, hands-on learning. One of her classes, after studying late 19th-century French art and the rise of the poster in Paris, mounted a show of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lithographs in the Katz Gallery. “We selected 18 examples [most of which have been bequeathed to the museum from the private collection of Andra and Irwin Press ’59, who lent the prints to the Block for this exhibit] and curated an exhibition that ran during the winter quarter,” Clayson says. “Each student took complete responsibility for one work and researched the pieces thoroughly in order to write wall texts and a 15-page research paper. Thinking back on it now, it’s a bit of a miracle that the students accomplished what they did so well and so quickly.” (Read more in "Collections: Toulouse-Lautrec's Paris Prints," summer 2015.)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Aristide Bruant (dans son cabaret), 1893, lithograph. Collection of Andra and Irwin Press.

The Block’s staff supported Professor Clayson and her students, ensuring that part of the learning experience included what it means to realize a museum exhibition from the inception of an idea to its final presentation to the public. Exhibitions by students that are created during a course also teach collaboration and problem-solving as a group. Students learn how to develop a shared vision based on consensus building and a free exchange of ideas.

The Block’s upcoming exhibit on Charlotte Moorman raises an issue that goes to the heart of every contemporary art museum’s mission: The definition of what constitutes “art” is constantly changing. (Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, after all, started out as advertising.) Moorman worked outside the mainstream art world of her time, organizing 15 New York Avant Garde Festivals between 1963 and 1980 as a way of presenting new creative forms. In the early 1970s, not everyone who saw Moorman playing a cello made from television sets overlaid with strings would have characterized the performance as art. But today, art historians do.

Right now, social media is upending many conventional assumptions about what’s worthy of being shown in a museum. Is a cellphone selfie a self-portrait? Does using Instagram filters mean you’re not a real photographer? “The Block is very engaged in those types of questions and looking at the bigger picture,” says the Grey Gallery’s Lynn Gumpert. “University museums have a key role to play in this expanded visual environment.”

For Corrin and her staff, the ever-changing nature of art is what keeps things interesting. “A museum should inspire people to see and think in new ways,” says Corrin. “When I was a student, every lecture was a discovery, and my ideas were challenged every day. That’s what an education should be. I want all of our visitors to walk in to each new exhibit and be surprised.”

As for that central question of what it means to be a university art museum? “We’re the shop window for the many things that make Northwestern unique,” she says. “We want to make those resources and that knowledge more accessible and help visitors make meaning of them.”

Through outreach and inventive programming, Corrin envisions a day when the Block is as much a campuswide resource as the library: “You shouldn’t be able to graduate from Northwestern without having visited us at least once.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email