Five Questions: Paul Pasulka

Interview by Zach Basu.

Skin for Skin is being produced by the Agency Theatre Collective and directed by Mike Menendian of the Raven Theatre. It will run at Rivendell Theatre in Chicago from Feb. 28 to April 2, 2017.

"With compelling performances, adroit direction (Michael Menendian), and a poignant script by Chicago playwright and psychologist Paul Pasulka, Skin for Skin brings back the initial feelings of shock, shame and revulsion that Abu Ghraib evoked," according to a review of Skin for Skin.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

Feinberg psychologist tackles ethical questions about enhanced interrogation procedures in new play inspired by events at Abu Ghraib.

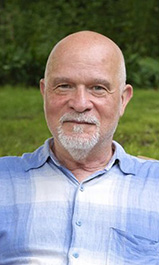

Paul Pasulka ’83 GME, ’85 PhD of Chicago is a clinical psychologist on faculty at the Feinberg School of Medicine. More than a decade ago he stumbled into a playwriting class at Chicago Dramatists, where he says he felt at home from the moment he walked in the door. Since then he has written more than a dozen plays, including Skin for Skin, which will run at Chicago’s Rivendell Theatre from Feb. 28 to April 2. Northwestern magazine's Zach Basu chatted with Pasulka for our "Five Questions" Q&A.

Paul Pasulka ’83 GME, ’85 PhD of Chicago is a clinical psychologist on faculty at the Feinberg School of Medicine. More than a decade ago he stumbled into a playwriting class at Chicago Dramatists, where he says he felt at home from the moment he walked in the door. Since then he has written more than a dozen plays, including Skin for Skin, which will run at Chicago’s Rivendell Theatre from Feb. 28 to April 2. Northwestern magazine's Zach Basu chatted with Pasulka for our "Five Questions" Q&A.

Can you describe the plot of Skin for Skin?

The structure of Skin for Skin is based on the Book of Job. The short story is this: God told Satan that Job is a pious man who never cursed him and always worshipped him. Satan replied, “Sure, he’s the richest man in the world. He’s got a great family. He’s got everything. What reason does he have to curse you? Give me five minutes with him, and then we’ll see if he curses you.” And God said, “Do what you want, but don’t touch him.” So in the next scene, Job is penniless, his family has all been murdered, he has nothing, and his friends collect around him to question what he must have done to insult God. This is where the philosophical question of “Why do bad things happen to good people?” begins.

Job eventually tells his friends, “I have done nothing to offend God, but I want my day in court with him. I want to contest God.” God comes down and admonishes Job, refusing to give him his day in court.

My “Job” is named Ayyub, and he is an Iraqi-American contractor in Baghdad who comes under suspicion of abetting terrorism and ends up in fictionalized black site prison [a secret prison used by the CIA to interrogate suspected enemy combatants] in Iraq. There, he is subjected to enhanced interrogation techniques without ever receiving his day in court.

Where did the inspiration for the play come from?

I was attracted to this story because psychologists in the United States played a huge role in bringing the enhanced interrogation techniques to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba and then to the black sites, like Abu Ghraib in the Middle East — and they profited quite handsomely from it. And in fact, the American Psychological Association rewrote their ethics code to correspond with the behavior of the Bush administration in using psychologists in these techniques.

That was as much inspiration as anything else. During the beginning of the Iraq War, which I thought was a horrible mistake, I found myself to be very, very depressed by the whole situation. I had begun writing plays a number of years before then. Once the Abu Ghraib story hit, I was inspired to write about the cruelty of the situation. And of course, I had read the Book of Job many times and had always been attracted to it — it’s a wonderful piece of poetry. The two stories just meshed together in a way that I thought was compelling.

So the play is a fictional story that is based on the Book of Job. Does that mean that there are divine elements to the plot?

God shows up, but He doesn’t necessarily save the day. There is a discourse between Ayyub and God. I don’t want to spoil too much, but the American military is also playing God in this situation. Basically, what they have said to the prisoners at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo is that you don’t have a day in court. We don’t recognize your right to have a day in court. And we are God, in this situation. How many prisoners do we still have at Guantanamo Bay who haven’t been charged with anything? The parallels are compelling.

Did your career as a psychologist shape your reaction to the enhanced interrogation techniques?

Without a doubt. I’ve worked with many people who have been traumatized, both physically and psychologically. I’ve worked with the Bluhm Legal Clinic at Northwestern’s law school to evaluate people who have been wrongfully imprisoned for some 20 to 30 years, to do evaluations on the effect that this has had on people, many of whom have been exonerated by DNA evidence. So this is something that is very clearly close to my professional and personal beliefs.

How do you reconcile your two careers?

Well if you think about it, writing a play is very much like doing a psychological evaluation or conducting therapy. Someone comes into your office, you know very little about them, they have a conflict — and over the course of weeks or months in dialogue or monologue, you get their whole life. You get the intimate details and you get to understand all of the backstory, all of the history, all of the other characters involved in their life, and it’s all through monologue and dialogue.

So I believe that in a lot respects, being a psychologist, a therapist and an evaluator has been an excellent training ground for writing plays. And on the other hand, I also think playwriting has helped me learn to listen carefully to what my clients tell me.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email