|

In July 1918, a young Ernest Hemingway wrote: “I can’t break the old habit of writing you whenever I get a million miles away from Oak Park.”

Milan, Italy, wasn’t a million miles away from Illinois, of course, although it must have felt that way to the 19-year-old Hemingway, who was hospital bound and writing his high school crush, Frances Coates. He wanted to hear from her, a fellow Oak Park and River Forest High School student he’d dated casually and pined for, even telling his older sister Marcelline to “call up Frances Coates and tell her that your brother is at death’s door. And that will she please, no excuses, write to him … . Tell her that I love her or any damn thing.”

Hemingway was recovering from wounds he suffered in Italy while a volunteer ambulance driver for the American Red Cross during World War I. He wrote Coates: “ … I was so unlucky as to dispute the occupancy of a Front line trench with an Austrian trench mortar and machine gun and came off very much second best with 227 nice separate and distinct wounds.”

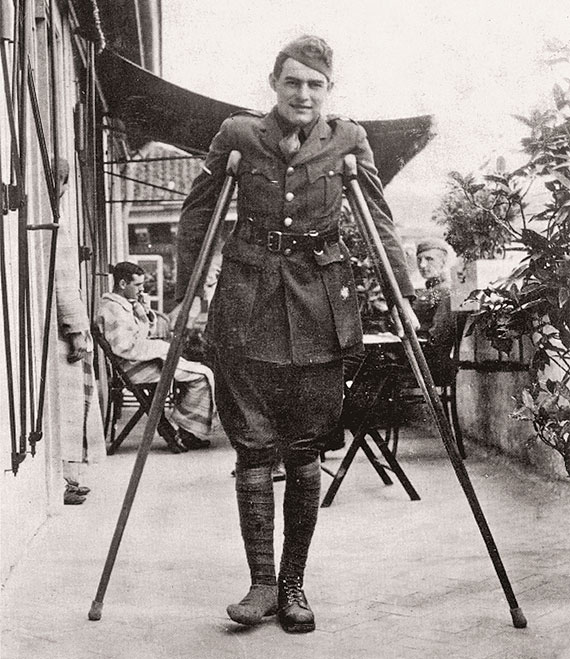

Ernest Hemingway in Milan, Italy, in 1918. © PVDE / Bridgeman Images

The excerpt is from one of two newly discovered letters that illuminate an unexplored relationship with Coates ’20, whose name shows up throughout Hemingway’s work. Early in his career, Hemingway used a version of her name — “Liz Coates” — in a controversial, carnal short story, “Up in Michigan” (1923). The name Frances also appears in two of his novels: The Sun Also Rises (1926) and To Have and Have Not (1937).

Coates went on to study at Northwestern, became a local opera performer and married another man. She saved some of Hemingway’s letters, but only these two remain in her granddaughter’s possession.

Almost no one knew about their connection, until I tracked down Coates’ only granddaughter, Betsy Fermano, at her home in Marblehead, Mass., after the publication of my book Hidden Hemingway. I’d seen Coates’ name mentioned briefly in Hemingway’s correspondence and wanted to know more. Not only did Fermano have two previously unknown letters from Hemingway, but her grandmother’s trunk was full of personal photos of Hemingway, newspaper clippings and an unpublished, 10-page remembrance Coates wrote about growing up and going to school with the aspiring writer.

“I didn’t think anybody would be interested in the letters,” says Fermano, 67. “My grandmother wasn’t really anybody famous. She was a beautiful, elegant person, but she was also very private about her life.” That includes her high school years with Hemingway, whom Coates saw as a troubled person who masked an inferiority complex with bravado.

“I didn’t think anybody would be interested in the letters,” says Fermano, 67. “My grandmother wasn’t really anybody famous. She was a beautiful, elegant person, but she was also very private about her life.” That includes her high school years with Hemingway, whom Coates saw as a troubled person who masked an inferiority complex with bravado.

But from an early age, his commitment to the craft of writing was undeniable. “ … Through and beyond and overall was a blinding talent and the greatest requisite of all: the determination and industry to develop the technique to use it,” Coates wrote in her remembrance of the young Hemingway.

In biographies, the women in Hemingway’s life are often pushed to the background. But, for the high school junior Hemingway, Coates was center stage.

Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker traced the author’s teen obsession with Coates to a high school performance of Martha, a three-act opera, staged in April 1916. Coates had only a minor role, but, Baker wrote, “Playing his cello in the orchestra pit, Ernest could hardly keep his eyes on the score. His friend Al Dungan, a gifted cartoonist, made a caricature of a boy with desperate eyes and labeled it: ‘Erney sees a girl named Frances.’ He was too shy to ask her to the Junior-Senior prom on May 19.”

They did have other outings, however. “Skating, walks, movies and opera,” Coates recalled, in the remembrance she wrote about Hemingway. They had an informal double date with Hemingway’s sister and her boyfriend on a canoe trip down the Des Plaines River, immortalized in photos Coates kept all her life. She was not, however, romantically interested in Hemingway. In fact, she was already being courted by high school classmate John Grace, whom she would marry in 1920.

Ultimately, Hemingway was a small piece of Coates’ full life, although evidence points to a correspondence that lasted, on and off, for decades. The majority of Hemingway’s letters to her were lost or discarded, but Coates kept his World War I letters tucked away until her death on March 5, 1988, at age 89.

Other items in the same trunk illuminate a rich life devoted to the arts. In an undated program for her performance in Claude Debussy’s

Pelléas and Mélisande, she is listed as “Frances Coates Grace / Singer of Songs and Solo Operas.” Coates became a diseuse, or performer who would condense operas and plays for modern audiences.

Coates’ love of music, specifically opera, began early in a musical household where siblings and “dozens of friends — all singers or with violins, guitars, mandolins” rolled back the rugs and “entertained each other and us for hours,” she remembered in a program she wrote in 1970 for Grace Episcopal Church in Hinsdale, Ill.

When Coates was 7, her mother, Catherine, began taking her to operas and concerts in Chicago featuring the theatrical and musical legends Eleanora Duse, Luisa Tetrazzini and Enrico Caruso. Frances kept and treasured the program for each event.

Coates performed throughout high school while caring for her mother, who was battling cancer. In 1916 Coates entered Northwestern, and her matriculation card from the College of Liberal Arts lists her date of birth (April 14, 1898), church affiliation (Episcopal) and birthplace (Battle Creek, Mich.). Coates was accepted into Delta Gamma sorority and was active in the class social committee. She studied music and voice under Lucie Lennox, who taught at Northwestern and later became her manager.

Coates left college in 1918 to take care of her mother but remained an engaged alumna. A photo published in the Oct. 20, 1923, edition of the Daily Northwestern features Coates, then 25, alongside Walter Dill Scott, an 1895 graduate of Northwestern and the University’s president, and Horace A. Goodrich. At age 86, Goodrich, a member of Northwestern’s first class of students, was promoting investment in the institution’s future.

Coates, whose friends called her FE for “Frances Elizabeth,” welcomed Katherine, her only child, in 1925. The family moved to Hinsdale, where Coates continued to perform. She sang with her daughter for weddings and church services — but “never a funeral, thank God,” Coates later wrote, reflecting on her career. She sought bigger stages, and got them, including a 1930 performance in Chicago’s Civic Theatre, where she sang a selection of folk songs and arias.

Although Coates admired Debussy, she was primarily interested in composers living in her time, particularly Richard Hageman, whose opera Caponsacchi, she performed “up and down the land.”

She loved opera because of “what it does for one: It induces and inspires the study of the world’s classics — for one has to learn poetry, drama and literature; it helps one understand the history of the world — and the history of man, for great events are ever portrayed in song or opera and the songs of a man are as much a part of him as the color of his eyes.”

In 1943, with World War II in full swing, John Grace was called to serve as a Navy commander in Washington, D.C., and the family left Illinois. Once there, she found new outlets for her music, singing charity concerts for the Red Cross and performing on the radio. She took an interest in the USO, particularly in music therapy for veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, then called shell shock.

Among Coates’ papers are two invitations to the White House, one during the Truman administration and another during the Franklin Roosevelt administration, though written accounts of those visits or concerts do not survive. A Washington Post review from the era declared that she “sang with taste, high musicianship, great dramatic ability and a charming informality that held her audience.”

After the war Coates moved back to Hinsdale with her husband and by the late 1940s took on a new role: grandmother.

“She was eloquent, refined and fascinating,” says Coates’ grandson Richard Riggs, 58, who lives in McQueeney, Texas. “She taught me about the fine arts and how they reflected the culture — that they were important.”

Coates gave Riggs piano lessons, and he remembers a home full of books and a dining table set formally, right down to the finger bowls. Although sophisticated and gracious, she was still the kind of grandmother, says Riggs, who threw a housecoat over her nightgown to rescue him when he slept through a late-night train stop.

Mandalee Barker, Fermano’s childhood friend, echoes that sentiment.

“She was truly the epitome of a lady. She could have been the wife of any president — she was that grand — but she always made you feel warm and fuzzy,” says Barker, 66. “She wasn’t snobby in any way.”

Still, traditions had to be honored. In 1968, Coates insisted on throwing a debutante party for her granddaughter. While the rest of the country was dealing with the “free love” of the hippies, Coates hosted a high tea in Hinsdale, complete with cotton gloves, flowing dresses and ballet dancers.

Coates was a longtime champion of the Lyric Opera of Chicago and raised thousands of dollars as a member of the Hinsdale Committee of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. She was an active member of the Three Arts Club, the Foundation for Arts Scholarship and the American Opera Society. She also took great pride in teaching Girl Scouts about opera and co-founded the opera club for a local high school, bringing so many students to see productions that the commuter rail company once had to add three extra cars to accommodate the throng of young opera lovers. She remained a booster of the arts until her death.

Over the decades, Hemingway and Coates kept in touch and exchanged correspondence sparsely. In her latest surviving letter to Hemingway, dated Oct. 17, 1932, she praised his foray into nonfiction with Death in the Afternoon, his book about bullfighting.

“Maybe I got your book all wrong, but what I liked about it, and what I felt all through it was that you were fed up with a lot of the critical goo you’ve been besprinkled with … to tie a writer to one mood and one subject (you to hardboiledness, tough guys, love, etc.); and I thought that this revolt of yours from a label was a grand thing to do … .”

Although she always felt warmly toward “Ernie,” she never regretted her life’s path — or her choice of life partner. On the envelope where she kept her photos with Hemingway, Coates wrote: “Ernie’s Pictures / And 25 years later ooh! Am I glad I married John."

Robert K. Elder is the author of seven books, including Hidden Hemingway: Inside the Ernest Hemingway Archives of Oak Park (Kent State University Press, 2016). He has taught as an adjunct professor at the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

Tell us what you think of the magazine in a short online survey by Jan. 31, and you’ll be entered to win an iPad.

E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.