|

If you happen to be counting floor tiles when Dan Ivankovich walks into the examining room, you might miss the way he has to duck to get through the doorway.

That’s the way it is, though, when the hairs on your head are nearly 7 feet off the ground. And that’s how it is for Dr. Dan, aka The Right Reverend, Doctor D, as the iconoclastic bone doc is called when he puts down his spine- or knee- or hip- reconstruction tools and picks up his six-string, fire-breathing Rodriguez Baritone Strat blues guitar.

Fact is, once you see the doctor’s supersize shadow spill across the floor, you’ll pay attention, all right.

Start with the boots — size 17, if you’re measuring. They’re heavy, black leather and studded with enough silver to set off the nearest metal detector. Then go up the legs, way up. He’s decked out this day — and most every day — in black surgical scrubs, with Maltese crosses stitched into the thigh and across the right hip pocket. Beneath the black leather vest, you can read the words “Bone Squad” spelled out just above where his big heart thumps.

Then there’s all the bling: Skull and crossbones on the middle finger. Hoop earrings. Maybe a chain, or two, depending on the day. And a black leather biker’s cap, pulled on backward, with the bill behind him and riding down his neck.

It’s not hard to be distracted by the getup.

It’s not hard to think this is just some bad-ass bone fixer who knows a thing or two about how to turn heads and take a star turn on the nightly TV news, say, when he air-dropped into Haiti after the earthquake of 2010 to see what miracles of mending he could pull from all the rubble.

Don’t miss the point here: Ivankovich, who graduated from Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine in 1995, might not look the part of the polished orthopedic surgeon. Nor might he practice out of some spiffy Gold Coast suite.

But this good doctor, who knows through and through the agony of defeat and the thrill of uncharted triumph, has carried his surgeon’s tools to the front lines of urban poverty and violence, and he’s hell-bent on serving the most underserved.

That might be the little kid with the shattered elbow who never got a simple plaster cast and had to suffer through the pain. Or the old woman whose odd-angled knees buckle beneath her with cruel regularity, leaving her to whimper on the bathroom floor for one whole morning recently, before she found her way to Dr. Dan.

Or, more often than not, it’s one of the shattered ones from what Ivankovich (FSM87, 95, GFSM02) calls “The Knife and Gun Club.” That, he explains, is when the knife blade or the bullet “doesn’t hit a vital organ” and leave the victim dead, but rather “it eventually penetrates a bone” that’s going to need the armament of plates and screws and pins and rods that is the everyday medicine of Dr. Dan.

One recent morning, in his red-walled clinic in Chicago’s rough-and-tumble West Side Austin neighborhood, where in just one ugly summer’s weekend a record-setting 75 felonies — that’s murders, rapes, gunpoint robberies and carjackings — were committed in a mere three-block radius, Ivankovich wasted no time in telling his story.

“I went from being all-everything to all-nothing in the blink of an eye,” says the former high school basketball star, who was admitted to Northwestern’s six-year Honors Program in Medical Education back in 1981. “I went from being the lead dog to having nothing. I was the underdog.”

It’s that lead-dog-to-underdog theme that is his leitmotif.

This long, tall dude, an All-American center at Glenbrook South High School who could once “shoot the lights out,” on any basketball court, anywhere, knows what it is to taste defeat. And he lives and breathes to upturn the bitter equation.

“It’s about pulling for the underdog,” says the 48-year-old surgeon, who reconstructs two to three spines a week, sees some 5,000 patients a year and still makes time for a handful of house calls every week. “Everybody wants a winner. The people who have no monetary means, no anything, who are just in the shadows, I wanna be their champion. I can take them from despair to functionality.

“That’s the journey: To take people to a place they can’t conceive of. This is the front line. This is the combat zone. We’re at war.”

Here’s the back story: Ivankovich, the Croatian-born son of immigrant physicians, had his dream scheme all etched out, back before he stepped into the bright lights at Boston University’s Walter Brown Arena for the Boston Shootout, a high-stakes streetball invitational, that long-ago summer of ’81.

“My life was set,” he begins. “It was all determined. I was on the golden path. I was gonna be in the NBA, then be a team doctor, play on the Yugoslav Olympic team. It was all very simple.” And very clear.

Until, as Ivankovich recalls, “I collided with somebody” at center court, midway through the tournament in the last week of June 1981. “I heard a huge pop. I fell on the ground. We were playing against Patrick Ewing’s Boston streetball team,” he interjects, for emphasis, perhaps.

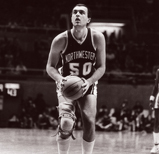

Dan Ivankovich, a high school All-American, had his collegiate basketball career cut short when he tore his ACL in 1981. During his injury-shortened career with the Wildcats, Ivankovich played in just 16 games over two seasons.

“My knee just blew up like a balloon. Back then, there was no MRI, no doctor was able to look at me and see what exactly it was. I was a 17-year-old kid. I took the plane back home on crutches. It took four doctors and one long month to figure out it was my ACL,” a ruptured and crucial ligament in his right knee. “Back then, a career-ending injury.”

Again, the doctor interjects: “Now, I would’ve been back on the court in four to six months.”

But not then. His dream scheme shattered, along with his ACL, there on the hardwood. “That’s what hurt the most,” he says, the pain still tingeing every syllable.

The 6-foot-11 kid with the 30-inch vertical jump, the kid whose right leg shriveled in the brace “that felt like being under house arrest,” his career, his shot at being a part of the turnaround basketball team at Northwestern, it was over before it even started.

Thirteen surgeries would follow. Ivankovich suffered setback after setback through that fall of ’81, when he was supposed to be the star.

Lost, he wandered into Annie May Swift Hall, searching for some now-forgotten class; when he looked up, he saw an “On Air” sign, all lit up.

What’s that, he asked, intrigued by his first brush with radio. Turned out, it was the studio of WNUR, Northwestern’s legendary FM radio station. And, turned out, the music director had an all-night blues show but no host.

Well, Ivankovich, who’d been playing classical violin since he was a little kid, had just started fooling around with a guitar, specifically a blues guitar. He leapt into the station’s midnight-till-8 a.m. slot. He’d been exposed to the blues while playing basketball on Chicago’s South Side, his high school years peppered with summer leagues and all-star teams that drew him far from white-on-white suburbia.

From the start, he says, “the blues impacted me. The poverty. The black culture. I loved it all.”

Wasn’t long till the would-be doctor was shopping for red velvet suits and green alligator shoes at Smokey Joe’s, a haberdashery on Maxwell Street; chowing down on greens and grits and black-eyed peas; and jamming with blues legends: Magic Slim, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, among the many.

“Basketball was taken away, and the blues slowly became available. That blues show was a saving grace for me. I found a crutch called music.”

Dan Ivankovich found a crutch in music after a serious knee injury ended his promising basketball career. Ivankovich, aka The Right Reverend, Doctor D, plays a six-string Rodriguez Baritone Strat blues guitar as a founding member, vocalist and guitarist for the Chicago Blues All-Stars.

Fast forward: Ivankovich ditched the tongue-twisting Croatian surname and took the on-air tag of The Right Reverend, Doctor D. His all-night WNUR show, Out of the Blue, was eventually syndicated in more than 60 markets. That led to a gig at a Chicago radio station and, eventually, a six-year stint as a radio producer in New York City.

Jack Snarr, then Feinberg’s associate dean for student affairs, saw himself as something of “a mother hen” to the roughly 700 Northwestern medical students. And he never flinched at Ivankovich’s zigzag path through med school, even if his particular hyphenations — playing at big-city blues clubs and radio stations — made him an iconoclast of the first order. “Eventually, Danny realized, medicine is where he belonged,” recalls Snarr.

Indeed, back at Feinberg after a six-year hiatus, Ivankovich threw himself into the toughest curriculum he could cobble together. He begged for an internship at the old Cook County Hospital, where in the first 30 minutes, he recalls, he’d “cracked open someone’s chest.”

It was in the halls of “County,” the nickname for that great gray stone edifice that was the temple of healing to the poorest of Chicago’s poor, that Ivankovich found the heart of what would be his rare brand of medicine.

He knew, right off, that his would be a surgical practice targeted at those who live on society’s margins, too often falling through every conceivable crack.

“I remember walking the halls of County, seeing all these throngs of people waiting in the halls. The question I heard myself ask is, ‘Wow, who’s gonna take care of all these people?’ And then I answered, ‘I will.’

“We’re covering some serious real estate,” says Ivankovich, ticking through the numbers: 1.4 million people in Chicago without medical insurance. Five- to six-year waiting lists in Cook County to see an orthopedic surgeon. Neighborhood after neighborhood where he’s the only orthopedist, for a combined total of nearly 300,000 residents to one storefront surgeon.

That’s why, in 2010, Ivankovich and his partner, Karla Carwile, launched OnePatient Global Health Initiative, a not-for-profit string of four freestanding clinics (three are up and running on Chicago’s West, South and North sides, with one more to open on the Southwest Side within the year), working with 14 inner-city hospitals in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. The organization also sends out teams into the communities, all of whom refer patients back to the clinics or the hospitals served by the OnePatient Global Health Initiative. The mission is to serve everyone who hobbles through the door, regardless of ability to pay.

“We take everyone. Period. Our staff is instructed: We take everyone who walks in,” says Carwile, a health psychologist, who joined forces with Ivankovich after helping him airlift spinal cord patients out of Haiti and realizing they were both set on bringing the best medicine to the poorest corners of the globe — be it a couple miles from downtown Chicago or the caved-in slums of the Third World.

“I don’t care if you bring me a plastic cup filled with pennies,” says Carwile, rushing a patient’s chart into an examining room. “I don’t care if you send me a dollar a month for the next 10 years.”

As Carwile puts it, “It’s not-for-profit, and there’s no profit in it.” Right now, they get reimbursed a mere $18 to $24 per patient visit from Medicaid if the patient happens to have Medicaid, though many do not. Although it’s a fledgling not-for-profit, angel investors (and big-time grantmakers) are already opening up their checkbooks.

Ivankovich is leaning against a counter, clicking through his smartphone to glance at an old man’s latest MRI. “I’m the equalizer,” he says. “I’m not a socialist. I’m not right wing, or left wing. I’m a populist. The issues here are global.

“Poor doesn’t mean you’re irrational, it doesn’t always mean you’re uneducated, and it doesn’t mean you lack basic understanding. It means you lack resources.”

He doesn’t pretend to be a saint. Or some almighty savior, albeit one who’s head to toe in black.

It’s simple math, according to The Right Reverend, Doctor D.

“It’s part of our debt to society. I just wanna be sure it’s paid.”

And with that, he darted down the hall and ducked beneath a doorway to see what he could do to get an old, teary-eyed grandma up and walking again.

Barbara Mahany (GJ82) was once a pediatric oncology nurse who dreamed of opening an inner-city clinic. She graduated from Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications in 1982 and has been a writer at the Chicago Tribune ever since.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Check out the ESPN The Magazine feature "Nobody Walks Alone" on Dan Ivankovich and his work with former NBA player "Massive Mike" Williams who was left paralyzed after a shooting in an Atlanta-area nightclub. Ivankovich and Williams were also featured in an "American Story with Bob Dotson" segment on NBC's Today Show.