|

|

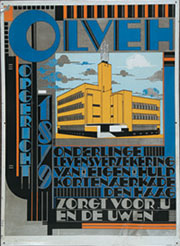

Dutch architect Jan Wils designed the metal poster for the Olveh Insurance Building, which he built in The Hague in 1930. Photography by Andrew Campbell

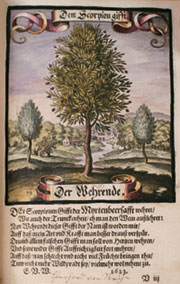

Special Collections is home to its share of artifacts, none older than the approximately 5,000-year-old Mesopotamian clay tablets with cuneiform carvings, such as this one. Curator Russell Maylone says, "No one knows how they got here."  The Ministere des Finances after the 1871 fire. The Siege and Commune of Paris Collection includes images of the devastation of Paris.  A costume design from the Gate Theatre by co-founder Micheàl MacLiammoir. A note on the drawing from MacLiammóir to the actor reads, "Dear Sheila, You'll look much lovelier than this. Good luck and love — Micheàl."  One of 200 coperplate engravings in a book by Matthäus Merian. This piece is in the membership history for Fruchtbringenden Gesellschaft, or the Society of Fruit-Bearing Trees, the first German literary society of 1629. Each member was portrayed as a flowering tree or shrub. |

You have to be really motivated to make it to the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. That is, if you even know it exists. (In my four years as an undergrad at Northwestern — as a history and communication studies major, no less — I never heard of it.) To get there, start at the University Library’s main entrance, walk downstairs and veer left. Next, follow the winding corridor that leads to stately Deering Library, an example of homage to Gothic architecture that seems to have been transplanted from Oxford. Walk up two flights of broad stone steps, their surface worn down by generations of visitors. This will bring you to the grand Reading Room that houses the library’s Art Collection. But you’re not there yet. Take a sharp right and you’ll enter the eclectic world of Special Collections. A library within the main library, Special Collections houses just what it says: collections that are “special” for their historic or scholarly value. Pieces are categorized by theme, be it Franklin Delano Roosevelt, fly-fishing or Italian Futurism. “The department doesn’t cover every intellectual thread represented by the vast range of books in the main collections,” says Russell Maylone, curator of the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. “But for those threads it chooses to follow, it follows in greater depth and often with unusual materials that couldn’t and wouldn’t be in the stacks.” That means that maps, sketches, historic newspapers and photos all make up part of Special Collections, along with about 200,000 books, pamphlets and periodicals. Special Collections encompasses thousands of one-of-a-kind pieces, but they’re not locked up in dust-proof vaults. Walk into the Special Collections library and you’ll be struck by how accessible it all seems: wooden tables are scattered with leather-bound books, manuscripts encased in manila folders and document boxes filled with fragile papers. A student leans over a large open volume, diligently taking notes. Bookshelves with carved-wood details line the walls, and stained-glass windows give the room an old-world feel. Yes, there’s a computer tucked in the corner, but otherwise you could be in an academic library circa 1900. Some of the materials in Special Collections date back to the founding of the University in 1851. Many collections came to the library through donations or bequests; others were purchased, and some have been built up piece by piece over many years. The result is a melting pot of subjects, from history and art to science fiction and feminism. “These pieces are unique,” says University Librarian David Bishop. “These are the things doctoral dissertations are made of, pieces that support many of our graduate programs in the humanities. When you look at printed materials, all research libraries carry more or less the same books. It’s through special collections that each university develops its own character.” Here’s a small taste of what you’ll find if you dig through the collections: underground newspapers printed throughout the United States in the 1960s, along with handouts, posters and other papers; letters written by D.H. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot and William Butler Yeats; memorabilia from the career of Ira Aldridge, a 19th-century African American actor who starred in Shakespearean plays throughout Europe (including a belt he wore while playing Othello); hundreds of movie and television scripts, from Adaptation to X-Men; posters from the Spanish Civil War; 20 volumes of Edward Curtis’ The North American Indian, with its iconic photographs of Native Americans; blueprints of buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright; pamphlets from the French Revolution; and, thanks to the Joseph Spear Beck Angling Collection, two fishing rods and about 1,000 flies for fly-fishing. Sound overwhelming? Many of the collections do fall into two major themes: the history of 19th- and 20th-century social movements, and collections relating to 19th- and 20th-century artistic works including theater, literature and visual arts. According to Alice Schreyer, director of the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago Library, Northwestern’s collections of 20th-century avant-garde artistic and literary movements, women’s collections and theater holdings are particularly well known in academic library circles. “The strengths of Northwestern’s Special Collections are highly regarded both locally — among other Chicago special collections libraries and librarians — and throughout the broader library community,” she says. One of the library’s most prominent collections relates to the Siege and Commune of Paris in 1870–71, a relatively short historical period that had enormous repercussions. When France went to war with Prussia in 1870, the city of Paris suffered four months of siege from German troops, including an intense artillery bombardment that ravaged the city. After Paris’ food supply ran out, an armistice was signed; not long after, a radical communal parliament took charge and attempted to institute a number of progressive social changes. Although the Commune lasted only a few months, it sparked hope in future revolutionaries worldwide, influencing the early work of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and others. Northwestern’s Siege and Commune Collection includes photographs,

cartoons, political posters, letters and poems from this turbulent period,

including pictures of the many women who played important political

roles (with so many men fighting at the front or being held as POWs,

women stepped in to take their places). Photographs from the era bring

home the devastation of Paris in striking images: elegant building facades

pockmarked from artillery shells; historic palaces gutted by fire; grand

boulevards closed off by blockades. As the mother of a young child, Clayson didn’t want to spend long periods abroad for her research. The Siege and Commune Collection allowed her to work with valuable primary sources right in her own back yard. Few social movements were as wide-ranging as the spread of women’s liberation in the 1960s. The Women’s Collection is a vast archive of feminist material, including books, pamphlets, newsletters, calendars and even political buttons. The collection is especially known for its wide range of periodicals; although most of the magazines and newsletters date from 1965 through 1985, the library has about 400 current subscriptions to periodicals published by women’s organizations around the world. Current and expired titles such as Celibate Woman; Womanspirit: The Irish Journal of Feminist Spirituality; Women Against Military Madness; and Conscience: Catholics for a Free Choice show the many diverse paths that feminism has taken in the last quarter-century. (Soviet Woman, alas, ceased publication in 1990.) Many of the pamphlets and posters in the Women’s Collection were considered just pieces of paper at the time they were printed; it is only with time that they have taken on the importance of historical documents. Similarly, many early 20th-century modern art movements were unappreciated at the time, but pieces associated with them are now coveted by art lovers. Special Collections is well known for its Dada, Futurist, Surrealist and Expressionist books and periodicals, which were purchased relatively cheaply years ago but have since soared in value. (“If you’re interested in German Expressionism,” jokes Maylone, “we can bury you.”) Jens Nyholm, the University librarian from 1944 to 1968, traveled to Europe regularly in the years after World War II, buying up books of avant-garde artworks that no one was interested in at the time. Now 50 years later, many of those books are extremely valuable collectors’ items. Thanks to Nyholm’s travels, Special Collections also has the largest U.S. collection of World War II–era European underground publications. Because of Northwestern’s highly regarded departments of theater and performance studies, Special Collections has a broad range of theater materials. Highlights include playbills from the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, for 1810–29; 16,000 plays from 19th-century Spain; and correspondence between Edward Albee and Sir Michael Redgrave before the Edinburgh Drama Conference of 1963. But the most prominent collection is that of the Gate Theatre of Dublin, Ireland, which was founded in 1928 by Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir. The Gate, known as the home of European and experimental theater, was credited with being adventurous and far-sighted while bringing many classic works of contemporary drama to the stage. (It’s also the place where Orson Welles got his start.) You wouldn’t expect to find the archives of one of Ireland’s

most prestigious theaters sitting in Evanston. (The archives were sold

to Northwestern as part of a Gate Theatre fundraising push.) But the

Gate Theatre collection shows the challenge of preserving what is, by

its very nature, an ephemeral art. A performance takes place onstage

at one specific time; when the actors walk off, the work is gone. But

flip through the Gate archives and you can almost imagine the plays

unfolding before you. Scrapbooks are filled with clippings of newspaper

reviews; publicity photos capture a cast in full costume. Especially

fascinating are the “Productions Boxes,” filled with all

the papers that went into making a show: costume sketches, lighting

plans, musical scores, copies of each cast member’s script, prop

lists. From these disparate pieces, a moment of theater history can

be briefly recaptured. Estimated value? $10 million. Other one-of-a-kind items are tucked away in a conference room behind the main Special Collections reading room. The oldest pieces date back about 5,000 years: clay tablets from Mesopotamia with cuneiform carvings that remain sharp and clear. Maylone discovered the pieces in a box when he first arrived to work at the library. “No one knows how they got here,” he says. Works from the days before printing include a 15th-century French book of hours, filled with intricately detailed illustrations, and a hand-written Koran, dating perhaps to the 17th century, complete with leather carrying case so the book could be strapped on an arm and worn into battle. With so many disparate publications and objects, you never know what you’ll find in Special Collections — or where to find it. That’s where the staff comes in. Maylone, who has been curator of Special Collections since 1969, is a fountain of anecdotes and suggestions, pointing visitors toward just the piece that will pique their interest. “I think of the Special Collections librarians as valued colleagues and friends in so much of the work I do,” says Carl Smith, Franklyn Bliss Snyder Professor of English and associate director of American studies. When Smith mentioned that he was planning an American studies seminar on the formation of the new nation, Maylone pointed out a collection of funeral orations given after the death of George Washington. “I had no idea that this collection even existed,” says Smith. “I assigned each student one of the orations, and the subsequent discussion of ideas of leadership in the America of 1799 made for a wonderful class.” Smith also confesses to a particular liking for the Special Collections library space itself: “I love sitting in that room and working. It feels like a library as much or more than any space in which I’ve worked, and that adds an extra measure of enjoyment.” You don’t have to be a faculty member to soak in the atmosphere. The Special Collections are surprisingly, refreshingly accessible. “Anyone can walk in the door and use the materials,” says Maylone. “We don’t have any armed guards.” Many libraries require visitors to don special gloves and surrender all their pens and other writing implements before handling historic documents — not at Special Collections. It’s even relatively easy to arrange for photocopies. The library is open from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, but it is also open Saturday mornings to accommodate people who work during the week. If you can’t make it in person, you can check out the Special Collections Web site (www.library.northwestern.edu/spec). Most of the collections are described online; there are also two “digital” collections, “The Siege and Commune of Paris” and “William Hogarth and 18th–Century Print Culture,” complete with photos and other artwork. Putting collections online is yet another way the library makes material as accessible as possible, one of Maylone’s top priorities. In his almost 35 years with Special Collections, Maylone has sorted through more boxes and papers than most can imagine. But ask him about his favorite pieces in Special Collections, and he doesn’t mention a book, or a poster, or a photograph. Instead, he mentions two printing presses and drawers full of type. One of his most rewarding experiences as curator, he says, was the time he taught an English class how to set type and then print it, to get a new perspective on the life of Virginia Woolf, who ran a publishing company, Hogarth Press, with her husband, Leonard. The printing press, for Maylone, sums up all that is special about Special Collections. “With an illuminated manuscript, only one person at a time could see it, and it never moved beyond a very small circle,” he says. “But when you start printing, books can move in circles that are much bigger. They can literally begin to change what knowledge is. Ideas that get shared get changed, and from that change new ideas get generated.” Perhaps that explains why Maylone is so happy to share the pieces in Special Collections with visitors. “We’re open to the curious,” he says, “people who want to think in new and different ways.” Elizabeth Canning Blackwell (C90) is a freelance writer based in

Skokie, Ill. |