|

The March 22, 2016, Presidential Preference Election drew large crowds of voters throughout Arizona.

On the ballot were six Democratic presidential candidates, two representing the Green Party and 14 Republicans. In Maricopa County, one of the nation’s most populous and home to Phoenix and Mesa, thousands of people lined up to cast their votes. The lengthy lines were partly attributed to voter interest in the contest.

But something else was at work that day. The local election officials had been steadily reducing the number of polling places in the county: from 400 in 2008 to 200 in the 2012 election and down to only 60 last March. It was also the first election in which the state’s more than 1 million independents were not permitted to vote unless they reregistered as a member of one of the three parties with candidates on the ballot.

The results included locations running out of ballots, lines lasting up to five hours, thousands of independents turned away at the polls and people voting at midnight in some locations. In other places people who were in line when the polls were scheduled to close were turned away.

Critics argued that the measures disproportionally affected traditional Democratic constituencies: seniors, students, workers who could not afford to be absent from their job for five hours, single mothers, people of color. In a postelection survey, the Arizona Republic found that most counties had enough polling places to average 2,500 or fewer eligible voters at each location. In Maricopa County, which has large Latino and Native American populations, it was one site per every 21,000 voters.

Testifying a week later at a legislative hearing on what went wrong, Maricopa County recorder Helen Purcell, whose office ran the election, said, “I screwed up.”

State Democratic officials were not surprised by the long lines. “To be honest, we had an idea that there could be problems,” says Jim Barton ’93, counsel for the Arizona Democratic Party. A Maricopa County supervisor “had raised concerns about the number of polling places ahead of time. But we were surprised that cuts [in the number of polling places] were as dramatic as they were. The connection to Shelby County is pretty direct.”

In 2013, by a 5-4 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder essentially ruled that a provision in the 1965 Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional. The ruling invalidated a provision known as preclearance, which required that jurisdictions in portions or the entirety of 16 states had to seek approval for changes in their voting laws from the U.S. Department of Justice. The states had histories of voter suppression and included Arizona and several in the South (Shelby County is in Alabama). The court said that the more than 40-year-old formula used to determine which jurisdictions should be subject to preclearance was outdated.

Barton explains that, had the Supreme Court not removed the preclearance requirement, the county’s decision to greatly reduce the number of polling places likely would not have passed muster.

“In submitting their package [of logistical plans] to the Department of Justice, Maricopa officials would have realized that this voting change was problematic — and perhaps not have made it,” he says. “That’s because the Department of Justice would have required specific evidence that the change would not have an adverse impact on access to the polls.”

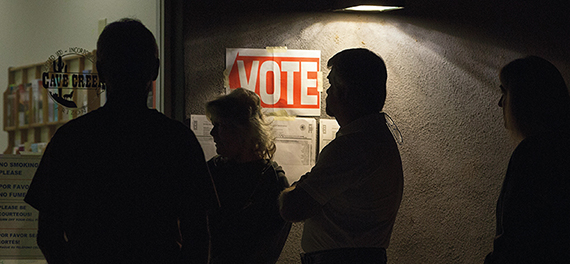

People line up early in Cave Creek in Arizona’s Maricopa County to vote in the March 22 presidential primary election. Photo by Nancy Wiechec.

Although former Supreme Court Associate Justice John Paul Stevens (see "A Justice for All," spring 2009) voted to uphold a voter ID requirement in a 2008 case (Crawford v. Marion County Election Board), he said in a recent interview, “The Shelby County decision was quite wrong. And I thought the Court shouldn’t have taken the case. The Court failed to give adequate weight to Congress’ decision that the statute [on preclearance] should be kept.”

Writing in the New York Review of Books on Aug. 15, 2013, Stevens ’47 JD, ’77 H, who retired in 2010, explained, “The several congressional decisions to preserve the preclearance requirement — including its 2006 decision — were preceded by thorough evidentiary hearings that have consistently disclosed more voting violations in those states than in other parts of the country. Those decisions have had the support of strong majority votes by members of both major political parties. Not only is Congress better able to evaluate the issue than the Court, but it is also the branch of government designated by the 15th Amendment to make decisions of this kind.”

Wylecia Wiggs Harris ’84 MBA is executive director of the nonpartisan League of Women Voters in the United States in Washington, D.C., a 96-year-old organization dedicated to protecting, educating and engaging voters. “Challenges to voting rights have been cyclical,” she says. “Recently, between 2005 and 2015, we’ve seen a stark increase in voter suppression laws, laws that had previously been blocked by the courts and state legislatures. It’s clear that specific demographics of the electorate carry a greater burden of these laws — communities of color, young people, single women, women in poverty, the disabled. We want a representative electorate that reflects a diverse nation.”

The national office of the League joined state leagues in Alabama, Georgia and Kansas in a lawsuit this year challenging the rules in those states that proof of citizenship is required in order to register to vote. State leagues have also been in court in five states fighting restrictive voter laws.

The Shelby County decision led to a rash of new voting restrictions around the country, though the trend started a few years earlier. Since the 2010 midterm election, 22 states have initiated new restrictions, ranging from a strict photo ID requirement to cutbacks in early voting, according to the New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice.

The efforts are justified by state legislators and governors as a protection against voter fraud. Yet there is scant evidence that voter fraud actually exists on a level that could affect the outcome of an election.

“I recognize that these statutes are motivated by a desire that Republicans win elections and Democrats lose. That is not the correct motivation for an impartial government. There is clearly a partisan motivation for this, though it’s not necessarily unconstitutional.” — Retired Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens

Loyola Law School Los Angeles professor Justin Levitt investigated the claim of widespread voter fraud by reviewing votes from general, primary, special and municipal elections from 2000 to 2013. In the more than 1 billion votes cast in just the primary and general elections during that period he found only 31 legitimate cases of in-person voter fraud that a voter ID law would have prevented.

Instead, many critics consider these widespread efforts to restrict voting access to be a classic example of a solution in search of a problem.

“I recognize that these statutes are motivated by a desire that Republicans win elections and Democrats lose,” says Justice Stevens. “That is not the correct motivation for an impartial government. There is clearly a partisan motivation for this, though it’s not necessarily unconstitutional.”

Northwestern law professor Andrew Koppelman sees it more harshly. “These laws, and everybody knows it, exist only for the purpose of disenfranchising some voters, making the United States less Democratic than it would otherwise be,” he says.

“This is certainly how it looks to me given that you see these voter ID laws turning up all over the country in places where there have been zero episodes of voter fraud,” Koppelman adds. “And, as Sherlock Holmes famously said, ‘Once you have eliminated the impossible, what remains, however improbable, must be true.’ ”

Testimony at a trial in federal court in Milwaukee this past May bolsters these arguments. Ten voters and two advocacy groups challenged the constitutionality of Wisconsin’s voter ID law, one of many new, more restrictive measures put in place in the state in the past five years. Several witnesses gave damning testimony about the lawmakers’ real intentions.

On the trial’s first day, a former staffer for a now retired Republican state senator described several Republican legislators in a private meeting as being “giddy” and “politically frothing at the mouth” over their belief that the proposed voter ID law would make it more difficult for some Democratic constituents to vote. One state senator was quoted by the witness as saying “What I’m concerned about here is winning, and that’s what really matters ... . We better get this done quickly, while we have the opportunity.” (A U.S. District Court judge placed an injunction on the Wisconsin voter ID law in July, allowing citizens without a state-issued ID to vote after signing an affidavit that explains why they were unable to obtain an acceptable form of photo identification.)

[Editor’s note: Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s communications office and the two Republican leaders of the state senate did not respond to this reporter’s requests for comments on the state’s voting laws.]

However, when Walker signed the voter ID bill into law in May 2011, he promoted the bill’s fraud prevention merits, even if it only stops one case of fraud. “To me, something as important as a vote is important, whether it’s one case [of fraud] or 100 cases or 100,000 cases,” he said at the time. “Making sure we have legislation that protects the integrity for an open, honest and fair election in every single case is important.”

Among the many measures recently put in place by state governments around the country — eliminating volunteer registrars, shortening early voting days and hours, closing primaries to independent voters, for example — one of the most common is the requirement of a photo ID in order to cast a ballot.

In 2008 the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case of Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. It stemmed from an Indiana law that required voters to present a photo ID in order to vote. Plaintiffs argued that the ID was not necessary to prevent fraud because evidence of voter fraud was almost nonexistent. And they believed that the requirement presented an undue burden on people such as the elderly, nondrivers and minorities.

The Court, in a 6-3 vote, upheld the lower court’s finding that the photo ID law did not present an undue burden on voters. Justice Stevens sided with the majority and wrote the leading opinion.

But in the years since, he has come to question the decision, believing that the more he has learned about the impact of the law, beyond what was presented to the Court, the more he feels it was burdensome. “The plaintiffs’ lawyers hadn’t proven the adverse impact on the people they represented,” Stevens says. “The evidence didn’t support their claim. I think it [the decision] was unfortunate but not incorrect. We had to decide on the record that was presented.”

Jaime Dominguez, a lecturer in Northwestern’s political science department, is particularly concerned about photo ID laws that make voting more difficult for students. For example, in Texas a valid concealed carry permit is an acceptable ID for voting, but a student ID is not.

“In many ways I think [restrictions on the use of student IDs] curtails those efforts to get younger people involved in the electoral process,” Dominguez says. “It’s kind of a form of indirect disenfranchisement.

“You really want to make the ballot box more accessible, want to bring it closer to those individuals whom we oftentimes chastise for not being involved on college campuses. The fact that students can’t use their university ID, which already requires a [verification] process, is a shame. It really sends a message to young people — ‘We are going to make it as difficult as possible to get you involved.’ ”

Another law that has come under fire is the unusually strict measure passed by Kansas lawmakers in 2013 that requires new voters to present proof of citizenship in the form of a birth certificate, passport or naturalization papers when registering to vote. A federal district judge struck down the law in May, ruling that it violated a provision of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, which states that “only the minimum amount of information” is required to certify that a voter is eligible to cast a ballot.

Since the law went into effect in 2013, the judge found that more than 18,000 qualified voters had been unfairly barred from federal elections and that from 1995 to 2013 there were only three cases of noncitizens actually voting. The state of Kansas is appealing the ruling.

“The arc of history has bent toward the expansion of the right to vote,” says James Wascher ’78 JD, a former Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences adjunct faculty member who taught a seminar on the Voting Rights Act for several years. “In the beginning, only a privileged few — mainly white male property owners — could vote in the United States. Over time, broader classes of people have been brought into the tent, including persons of color, women and, most recently, 18- to 20-year-olds. But those who held the franchise shared it grudgingly, often only after decades of struggle.

“Now, however, we seem to be going backward, because efforts are being made to constrict the right to vote, rather than to expand it,” Wascher explains. “And whether the purpose of making it harder to vote is a partisan endeavor or to prevent alleged fraud or something else — and reasonable minds can differ on that — the end result is the same: fewer people will be able to vote.”

The League of Women Voters’ Harris says that proponents of more restrictive laws most often cite fraud prevention and preserving the integrity of elections as the reason for their efforts. “We want integrity in our election process,” she says. “And there is no evidence that voter fraud is a problem. We believe that elections have the most integrity when the most number of Americans are allowed to participate.”

Terry Stephan ’78 MS is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.