|

For me, and for a whole swath of people with whom I shared our campus in the early ’70s, a big chunk of the remembered landscape is occupied by Amazingrace. Sometimes referred to as a “community,” then as the Amazing Grace Collective, the Amazingrace Family and then just the ’Gracers, it was an officially sanctioned student organization — hard as that may seem to believe. It started as a coffeehouse and immediately became a magnet for live music; it evolved as a performance venue that served food and morphed into a live-and-work commune — a hybrid almost unique to the ’70s. Amazingrace was certainly unique at Northwestern in the 1970s: an unexpected bastion of hippiedom at one of the most conservative Midwestern campuses.

Amazingrace took shape in the basement of Scott Hall; a year and a half later, when it moved into the comparatively upscale digs of a decades-old wooden shack — where the pipes sometimes froze but the kitchen usually worked — it had become an integral component of campus life. Within another two years, for a brief period in the mid-’70s, Amazingrace stood as the most important music venue in Chicago — except, of course, for the fact that it was actually in Evanston.

And I got to watch the whole thing. Fellow students at WNUR played an integral role in the commune’s development, and my interest in music drew me in further; before Amazingrace closed, I had previewed countless shows at ’Grace for the Chicago Reader and reviewed many others for the venerable Chicago Daily News. I never belonged to ’Grace, but I had a ringside seat, and from the vantage point of several decades, the events of its history could have transpired on another planet — one delineated in my memory by iconic silk-screened posters, an ambitious menu of wholesome food, very long hair, very good sound and one humongous Irish wolfhound with the mien of an angelic child.

STUDENT STRIKE LEADS TO COFFEEHOUSE CREATION

“Amazingrace was born on the barricades of the 1970 anti-war protest,” says Darcie Sanders (WCAS79), a ’Gracer who today occupies the unofficial role of anthropological historian for Amazingrace studies.

No one was thinking that anything in particular might be taking shape in spring 1970, when a number of future ’Gracers found themselves shuttling food to the student protesters maintaining a pile of cast-off furniture and debris in the middle of Sheridan Road (in front of Scott Hall, at the south end of campus). In early May a student strike had erupted at Northwestern in the wake of shootings at Kent State University in Ohio, one of many campuses roiling in protest against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. The most visible sign of disruption was the barricade that cut off traffic on Sheridan Road for a week; it required 24-hour supervision to discourage University and Evanston police from moving in to dismantle it.

Here’s how Lindsay Wood Davis (SESP72), one of the early ’Gracers, recalls that chaotic period: “Some people arrived in this big blue bus from some commune in the area, and they parked by Scott Hall and were feeding people involved with the strike.” Scott Hall housed a rudimentary student union and, up until the beginning of the strike, the Scott Hall Grill, a University-run cafeteria in the basement. But the administration closed the fresh-food operation at the beginning of the strike, leaving the kitchen and its equipment unused. “Some of us sort of acquired part of the kitchen area of Scott Hall to help funnel food to that bus,” Davis continues. A couple of theater students, Andrew Frances (C71) and Dan Einbender (C72), and a music student named Lois (now “Loi”) Miller Eberle (C72) led the occupation of the grill and continued to serve food to the strikers after the blue-bus commune departed. Others occupied the student union, adorning much of the building (and most of the grill area) with exuberant graffiti.

As the academic year dawned in fall 1970, students found that the University had obliterated most evidence of the strike, installed vending machines and removed all the kitchen equipment from the Scott Hall Grill. All of this helped spur the creation of the Scott Hall Grill Committee, under the aegis of the Associated Student Government and spearheaded by some of those who had helped “liberate” the grill during the strike. And several of these folks harbored a not-so-secret desire to create a coffeehouse to replace the Scott Hall Grill.

In early 1971 the SHGC presented the “Report of the Scott Hall Grill Committee” to the administration. This one-page document argued that “the robot selection of food” (i.e., the vending machines) should be replaced by a new hot food service operated by students as a campus activity, with the University paying for a couple of new stoves as well as a regular supply of disposable plates and utensils. The SHGC also recommended that part of the huge Scott Hall kitchen be turned into a separate coffeehouse and small performance space.

According to the report, all the expenditures would come to less than the University had paid to paint over the graffiti during the summer. “I can’t overemphasize how much that action bothered people,” Davis recalls. “The University was in a state of chaos for the summer. Scott Hall remained this very cool space, and then they came in and painted it over. But we didn’t go away.” For good measure, the report recommended $50 be allocated for painting supplies to allow students to restore the graffiti. Surprisingly, the administration agreed: Cognizant of the need for a campus hub — and “still reeling from last year’s violence,” in Einbender’s words — the University recognized the SHGC as an officially sanctioned student organization and helped the group transform the kitchen area into a coffeehouse that could also accommodate student performers.

AMAZINGRACE, HOW SWEET THE SOUND

In spring 1971 the new space officially debuted, serving coffee and tea and pastries from Dunkin’ Donuts and Sara Lee. One evening, a folk duo — Norman Schwartz (C71) and his friend Carla Reiter — ended their set with an impromptu a cappella rendition of the well-known spiritual “Amazing Grace.”

Today, from his home in Santa Cruz, Calif., Schwartz explains, “Carla and I had worked up a version of ‘Amazing Grace’ for our own amusement. The song lends itself to beautiful harmonies [that] even a lousy singer like me couldn’t wreck.”

The appreciative response led Schwartz and other performers to close subsequent sets the same way; soon the whole audience was singing what had now become the club’s nightly finale. One night, after the line — “I once was lost but now am found/ Was blind, but now I see” — someone said something like “That’s kind of how I feel around here.” And Amazing Grace (two words) was christened.

As the Scott Hall Grill became known by its new name, the decision was made to splash “Amazing Grace” across the stage area. Lenny Karpel (McC73) painted the name across the top and down the right-hand side of a serving window. Inspired by both design and efficiency, he combined the words so that they pivoted on the “G” at the end of the first word and the beginning of the second. The result was a single, flowing neologism: Amazingrace (one word).

Amazingrace quickly grew in popularity, but the agreement between the SHGC and Northwestern had an expiration date; Amazingrace would need to vacate Scott Hall in the summer of ’72.

The administration had its reasons. First, with Norris University Center nearing completion as a bona fide student union, all of Scott Hall, which had more or less served that function, was slated to become office space. Second, with a schedule featuring locally popular artists and the occasional touring star, the club was drawing an increasingly larger number of noncampus patrons. But Amazingrace had inserted itself firmly into campus life — as proven by the hue and cry among the student body when news of its closing got out — and so the administration worked with the club’s founders to find a new home.

The result: Amazingrace would relocate to Shanley Hall — “Hall” being a somewhat grandiose name for a somewhat shabby rectangular structure, just east of Lunt Hall, that in a previous incarnation had housed the University’s Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps program (hence its common though incorrect nickname — “the Quonset hut”). The University would pay to build out the space, becoming for all intents and purposes the club’s landlord. The ’Gracers would crack down on underage attendance and the drinking of alcohol on the premises; and Andy Frances, who had earlier chaired the SHGC, would have no further contact with the administration. (Several administrators considered Frances a general thorn in their side; more to the point, he had in fact graduated and could no longer represent a “student organization.”) And with those conditions in place, the ‘Gracers debuted their new space on Nov. 3, 1972, presenting two of their favorite performers, local rocker Bill Quateman and folk singer Ed Holstein.

The audience continued to grow; a year or so later I described the club in an article in the Chicago Reader as “a big, open room with an excellent sound system, a thriving kitchen, a cafeteria-style counter, a piano, a few booths lining two walls, wooden floors, and some fine people. It has become probably the best coffeehouse and one of the top folk-music establishments in the Chicago area.”

FULL MEAL FRESH DAILY FOR $1

’Gracer Lenny Karpel works on a silk screen at Shanley Hall.

Amazingrace had also become a popular hangout for meals, especially lunch, among students looking for something more wholesome than cafeteria fare. The introduction of a regular lunch schedule was announced on one of the distinctive silk-screened posters that the ’Gracers regularly printed and distributed to promote performances. “Amazingrace presents FOOD,” it read, followed by a quotation from collective member Herbie Grimm (WCAS72): “If it weren’t for food, what would we eat?”

There were some days when that question begged an answer. While everyone pitched in around the kitchen, in true communal fashion, some had less aptitude than others for cooking. The introduction of cream of broccoli soup illustrates the point. “One day a pile of broccoli came in,” Sanders recalls. “I had never seen broccoli other than cut up in Chinese takeout. So I spent the better part of an hour shaving off all the tops, pushing them to the side of the cutting board, and had a nice pile of all the stalks when Andy Frances came by and very sweetly shook his head, patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘Darcie, the tops are what we eat.’ ”

Since they couldn’t serve the now mutilated broccoli as a vegetable, they turned it into soup, which became one of the most requested menu items that winter.

Over the next two years Amazingrace expanded its horizons on all counts. The food improved; the posters went from eye-catching to stunning, as the collective learned the finer points of using their silk-screen press; and thanks to the more tech-oriented ’Gracers (notably Lenny Karpel and Jeff Beamsley [McC72] and, later, Flawn Williams [C74] and Benj Kanters [C75, GBSM02]), the club boasted a sound system as good as any in Chicago and better than most.

ON STAGE: LUTHER ALLISON, THE GRATEFUL DEAD AND JOHN PRINE

The bookings now encompassed more than the folk heroes en route to legendry (Steve Goodman, Jim Post, John Prine), embracing the occasional bluesmen (Luther Allison, the Siegel-Schwall Blues Band); assorted other folk, rock and bluegrass acts; and at least one bona fide icon, the folk singer Odetta, then in her 40s and already a veteran of the ’50s folk revival and the ’60s civil rights movement.

“I remember we rented a tent for Odetta to use as a dressing room,” says Margot Myers (C75), one of the last two inductees into the collective. “We didn’t really have dressing-room space; performers hung out in the kitchen and changed in the restrooms. Somehow, that just didn’t feel right for Odetta. She was regal in bearing, an amazing musician, and we thought the world of her … [so] we pitched a tent outside the back door.”

Student demonstrators show their support for the Grateful Dead concert.

Names that would become better known throughout the decade — multi-instrumentalist Ken Bloom, the crystal-voiced singer Bonnie Koloc, the folk-rock band Redwood Landing, avant-garde jazz saxophonist Fred Anderson — made ’Grace a destination for the deeply entrenched music fans. When the ’Gracers got the chance to present bigger names to bigger audiences — such as the jazz-fusion Mahavishnu Orchestra or the Grateful Dead — they used Cahn Auditorium or the University’s basketball stadium, then known as McGaw Memorial Hall.

Sometimes the ’Gracers encountered musicians who could put even their laid-back student sensibilities to shame. The first time bluegrass-jazz fiddler Vassar Clements played the club, he surprised Beamsley and Davis by arriving at the airport alone, with no band and no plans to engage local players. “He said he didn’t need to hire a backup band because musicians always just ‘showed up’ [at his gigs],” says Beamsley. “We were in a panic. We weren’t sure any musicians were even aware that he was in town.” But sure enough, on that first date and all that followed, “Musicians just appeared out of nowhere, anxious to play with him,” says Myers. “So many guitars, banjos, mandolins — it was not uncommon for this bluegrass jam session to continue at our home after we closed up the coffeehouse.”

As Beamsley recalls, “Amazingrace was also a safe place for Evanston kids. … Campus security didn’t bother them as long as they were heading to Amazingrace, [which] … opened our eyes to the fact that our real audience was outside the campus boundaries and wasn’t determined by when school was in session. That was the beginning of our awareness that this was a business rather than a student activity.”

Of course, when dealing with musicians, especially in the ‘70s, “business” became a relative concept. One night, after a particularly successful weekend, Beamsley handed guitarist John Fahey — who only ever wanted to get paid in cash — $3,000, all in $20s. “It took both his hands to hold it all,” Beamsley recalls. “But rather than put the money away, he just asked me to help him carry his guitars to his car parked in the alley. I was happy to help because, even though it was Evanston, it didn’t seem wise to be there alone, with an armful of money, late on a Sunday night. We got to his car, and he opened the trunk, and it was filled with cash. He just tossed the new pile in, along with his guitars, and calmly closed the lid. ‘Nobody ever looks in the trunk,’ he told me.”

Through the entire Amazingrace experience ran a current of counter-culture defiance and left-leaning politics, along with the knowing irony that all this was taking place with the University’s compliance (if not its actual blessing).

“Like most everything else at Northwestern, the whole process was balkanized,” explains Sanders. “At the very highest level of the administration we had no friends at all — they thought we were disruptive, rude and disrespectful. And they were right; on this we agreed. Where we parted company was whether this was a valuable resource for the University community and for the changes going on around the country at the time. And there were definitely others in the administration who were very supportive, even thrilled, at the idea of a student-run, student-designed space.”

Of course, several of those who had designed it were no longer students, so they couldn’t live on campus. But in their living arrangements, too, the Amazingrace Family had broken new ground.

TOGETHER THROUGH LIFE

In summer 1971 a number of students who were then known as the Amazing Grace Kitchen Collective had occupied an abandoned student housing building on Sherman Avenue, paying no rent and challenging the University to remove them. By September they had dispersed to several shared apartments, but “the goal was always to live together and work together,” Sanders says. And in September 1972 they found a better way to do so: A dozen ’Gracers moved into a rambling three-story house on Colfax Street (at Sherman Avenue), purchased by Andy Frances’ mother, Evan, precisely to provide housing for her iconoclastic son and his brothers (and sisters) in music.

The residence on Colfax also served as overnight housing for many of the club’s performers and frequent other unexpected guests. “I woke up one morning, and Abbie Hoffman was there. He had spent the night in the basement,” Sanders offers by example. The house was also home to Davis’ dog, an Irish wolfhound named Shannon who stood about 3 feet tall on all fours. Shannon was as gentle as a kitten, but at least one well-known artist didn’t wait around long enough to find out. As Davis recalls, “[Guitar virtuoso] Leo Kottke was over one night, and he comes out of the bathroom, and Shannon’s there waiting to get a drink. Leo’s terrified of dogs. So instead of walking past her, he went back into the bathroom and climbed out the window.”

MORE THAN THREE'S A CROWD

Eventually, the communal spirit proved the undoing of Amazingrace as a campus phenomenon. In November 1973 the city of Evanston notified Northwestern that by allowing the collective to sell food, the University had violated a zoning regulation prohibiting commercial business operations on University land. To comply, Northwestern would need to shut down ’Grace’s food sales. In addition, the categorization of ’Grace as a “student organization” had come into question, because the organization now contained few actual students: All the founders, and all but two of the Amazingrace Family, had either graduated or dropped out.

Evanston statutes also held that no more than three unrelated persons could live under one roof as a “family.” The house on Colfax contained 12, and the city ordered them to leave the residence. The collective hired a lawyer from the American Civil Liberties Union to argue that the “unrelated persons” law was archaic and no longer applicable.

In January 1974 came a piece of good news: Amazingrace (the coffeehouse and performance space) reached an agreement to remain at Shanley Hall by changing its business model to fit under the umbrella of the Norris University Center. But three months later — on April Fools’ Day — came the bad news: In the case of Belle Terre v. Boraas, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in favor of existing New York law, which, like Evanston’s, allowed each municipality to define a “family.” By August of that year the collective had exhausted its appeals, and their house on Colfax could no longer be their home.

The physical breakup of the commune provided the incentive for a philosophical split as well, stressing a fault line that had been developing for some time.

AMAZINGRACE MOVES TO MAIN STREET

In fall 1974 about half of the ’Gracers headed west to Eugene, Ore., to expand upon the collective experience; a couple others went off to new ventures; and another half-dozen members stayed in Evanston to create a new Amazingrace at the Main, a commercial development under way near the corner of Main Street and Chicago Avenue, across the street from the “L” station. (Find out where all the ’Gracers are now.)

From left, ’Gracers Jeff Beamsley, Lenny Karpel, Darcie Sanders, Dave Conant (SESP72), Herbie Grimm and Benj Kanters at Amazingrace at the Main.

The new Amazingrace did quite amazing things. Ensconced in a much larger space, the club could accommodate more than 400 patrons — almost twice the capacity of Shanley Hall — most of whom sat on the carpeted floor. The club continued to earn plaudits for its first-rate sound, reasonable prices and decidedly “non-nightclub” atmosphere. The collective made especially strong inroads into jazz. Legends such as saxophonists Sonny Rollins and Eddie Harris and pianists Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner commanded the large but still intimate confines. It was also the go-to venue for a younger generation of jazz artists, including pianist Keith Jarrett, vibraphonist Gary Burton and guitarist Pat Metheny. Besides jazz, you could have heard Randy Newman, the Paul Winter Consort, David Sanborn, the Persuasions and Jimmy Buffett. The Piven Theatre Workshop performed, as did poets Charles Bukowski and Allen Ginsberg. Steve Martin played his first Chicago-area comedy shows at ’Grace, and one night, Henny Youngman appeared. But so did the tried-and-true folkies who had helped build the Amazingrace concept in the first place.

From mid-November 1974 through July 31, 1978 — when Jim Post closed out its run — Amazingrace at the Main dwarfed every other music venue in the Chicago area, in terms of the quality of its sound, the boldness of its bookings and the overall experience that it afforded listeners and performers alike. That’s another chapter entirely. But it has its preamble in the fractured politics, the communal vision, the dedication to music and the radical idea that even at Northwestern in the 1970s, you could think of a different way to do things and then actually make them happen.

“Many others wanted to live more communally, have a community built around food and music and were active politically,” Sanders says about those years. “Where Amazingrace was unique, I think, was in our level of commitment — and eventual success — in reaching those goals.”

EDITOR'S NOTE

Amazingrace celebrates its 40th anniversary this fall, Oct. 15–22, with special events on the Evanston campus during Reunion 2011 and concerts in Evanston and Chicago.

This fall (Oct. 18–Dec. 30) Northwestern University Library will host an exhibit of Amazingrace memorabilia, curated by assistant University archivist Allen Streicker (G80). He is also writing a book on Amazingrace that is scheduled to be published by Northwestern University Press in 2012.

University Library has also created the Amazingrace Project to raise funds to collect and preserve materials from the student collective, including more than 300 hours of live concert performances from the classic Shanley years.

CONTRIBUTORS

Neil Tesser (J73) has written on and broadcast jazz in Chicago for four decades, in venues ranging from the Chicago Reader to USA Today to National Public Radio to Playboy Magazine. He is the author of The Playboy Guide to Jazz (Plume, 1998) and has written liner notes for nearly 300 albums, receiving both a Grammy nomination and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers’ Deems Taylor Award in 2001. Tesser lives in Chicago.

Neil Tesser (J73) has written on and broadcast jazz in Chicago for four decades, in venues ranging from the Chicago Reader to USA Today to National Public Radio to Playboy Magazine. He is the author of The Playboy Guide to Jazz (Plume, 1998) and has written liner notes for nearly 300 albums, receiving both a Grammy nomination and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers’ Deems Taylor Award in 2001. Tesser lives in Chicago.

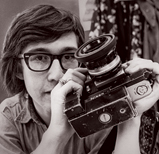

Charles Seton (C75, KSM78) took thousands of photos at Amazingrace concerts while he was an undergrad and graduate student. Many of his photos appeared in the Daily Northwestern and the Syllabus. A videographer and professional photographer today, Seton teaches digital imaging and photography through his company, Technology Explained Simply, in Mamaroneck, N.Y., where he lives. Seton first became interested in photography during high school when he worked on the yearbook staff. His father became rock concert promoter Bill Graham’s New York City lawyer when Graham opened Fillmore East in the East Village. Seton soon began to accompany his father to some of the concerts. It was at a Taj Mahal performance that Seton first went backstage to meet a musician, and soon after Seton began taking photos of the artists.

Charles Seton (C75, KSM78) took thousands of photos at Amazingrace concerts while he was an undergrad and graduate student. Many of his photos appeared in the Daily Northwestern and the Syllabus. A videographer and professional photographer today, Seton teaches digital imaging and photography through his company, Technology Explained Simply, in Mamaroneck, N.Y., where he lives. Seton first became interested in photography during high school when he worked on the yearbook staff. His father became rock concert promoter Bill Graham’s New York City lawyer when Graham opened Fillmore East in the East Village. Seton soon began to accompany his father to some of the concerts. It was at a Taj Mahal performance that Seton first went backstage to meet a musician, and soon after Seton began taking photos of the artists.

Amazing Memories

Share your memories of Amazingrace on the Northwestern magazine Facebook page.

Amazingrace Celebrates 40 Years

Amazingrace celebrates its 40th anniversary this fall, Oct. 15–22, with special events on the Evanston campus during Reunion 2011 and concerts in Evanston and Chicago.

This fall (Oct. 18–Dec. 30) Northwestern University Library will host an exhibit of Amazingrace memorabilia, curated by assistant University archivist Allen Streicker (G80). He is also writing a book on Amazingrace that is scheduled to be published by Northwestern University Press in 2012.

University Library has also created the Amazingrace Project to raise funds to collect and preserve materials from the student collective, including more than 300 hours of live concert performances from the classic Shanley years.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu