Then: Lab Discovery Powered Allied Fighters in Battle of Britain

Tell us what you think of the magazine in a short online survey by Jan. 31, and you’ll be entered to win an iPad.

E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

Petroleum pioneers helped develop the field of catalysis.

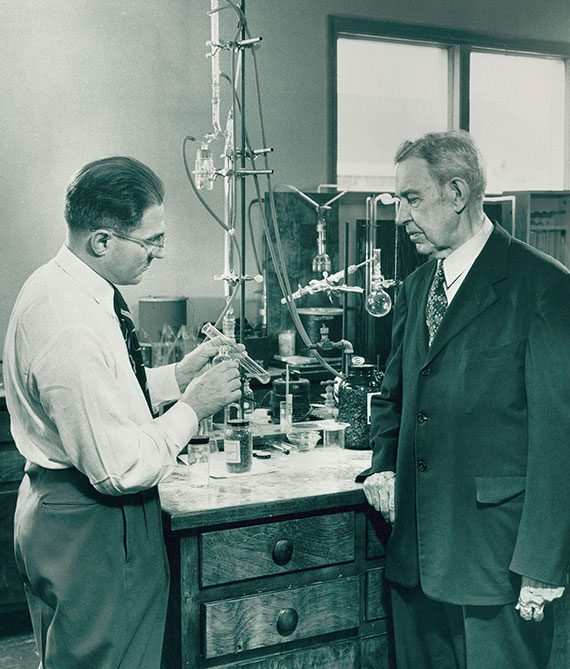

Herman Pines, left, and Vladimir Ipatieff at Northwestern’s High Pressure and Catalytic Laboratory in 1950. Their partnership may have never occurred if not for Ipatieff’s dramatic escape from Russia. Fearing that Joseph Stalin would imprison or murder him for his political beliefs, Ipatieff fled to the United States after representing Russia at a conference in Berlin.

In the summer of 1940, Nazi Germany began an aerial assault on Great Britain, with the intention of forcing the British to agree to a negotiated peace settlement. Outmanned in the air, the Royal Air Force received 100-octane fuel from the United States, which improved the speed and power of British fighter planes and allowed them to stave off the German threat.

The Battle of Britain was a crucial victory for the Allies during World War II, and it can be attributed in part to the work of two chemistry professors at Northwestern. Both immigrants, Vladimir Ipatieff, from Russia, and Herman Pines, from Poland, met in the early 1930s at Universal Oil Products in Chicago and worked in Northwestern’s High Pressure and Catalytic Laboratory, which was later named in Ipatieff’s honor. Ipatieff and Pines — decorated chemists who combined to publish more than 500 papers and hold more than 200 patents — discovered a revolutionary process to refine oil, using a catalyst to convert waste gases to high-octane aviation fuel, which gave Allied fighter planes an edge over the Germans.

In his work at Northwestern, Ipatieff developed the field of surface catalysis used extensively in refining petroleum byproducts into fuel components. He is regarded as a leading figure in the field of catalysis — a means to accelerate chemical reactions by adding a catalyst.

The Center for Catalysis and Surface Science and the Institute for Sustainability and Energy at Northwestern held a symposium on Sept. 7 commemorating Ipatieff’s 150th birthday. His legacy endures at Northwestern with the Ipatieff Lectureship at the CCSS and the Ipatieff Professorship in the Department of Chemistry, a position held by Pines until his retirement in 1970.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email