Race and Inequality in America

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Find Us on Social Media

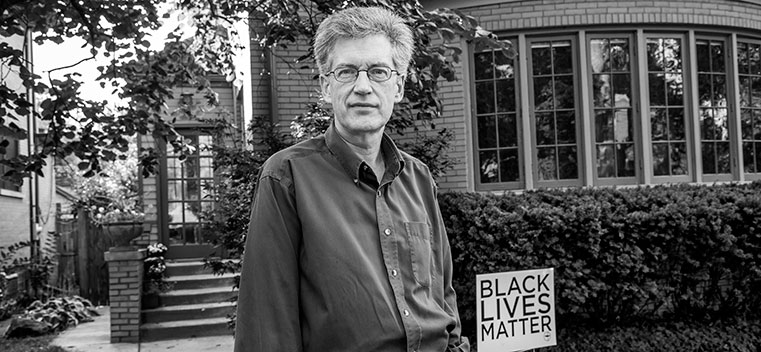

Social media has changed the conversation about racial violence in the United States, but professor Kevin Boyle says it will take more than talk and viral videos to deal with the nation’s history of segregation and inequality.

“There is no more fundamental issue in America than race,” says Kevin Boyle, who grew up in Detroit in the 1960s and ’70s, a time when race relations were “so raw and so brutal in that city.” In his 2004 book Arc of Justice, the American history scholar turned his attention to his hometown, focusing on the life of Detroit doctor Ossian Sweet, who was tried for murder in 1925 after two members of a white mob were killed while threatening Sweet’s home and family. The book won a National Book Award for nonfiction. Boyle, the William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern, continues to explore issues at the intersection of class, race and politics. He teaches several undergraduate courses, including a history of the civil rights movement and a quarterlong look at one lynching in Indiana in 1930.

Northwestern magazine’s Sean Hargadon sat down with Boyle to talk about racial violence, the Black Lives Matter movement, the weakening of the Voting Rights Act and the state of U.S. civil rights today.

Is this one of most volatile periods in race relations in this country since the 1960s?

I think it depends on your perspective. … From the African American perspective I suspect that racial volatility has been intense for decades and decades. What’s really changed, what’s made this moment really so volatile, is that it’s pushed its way into the mainstream of white America.

How has racial violence and racial inequality become part of the mainstream?

Social media has made all the difference in the world. From what has been reported, there’s not a dramatic increase of African Americans being killed by policemen in the last year. There’s been a dramatic increase in white America seeing African Americans being killed by policemen in the last year. That’s all a product of social media. I suspect, again, that an awful lot of African Americans, especially people who live in poor neighborhoods, will look at that footage and say, ‘That’s not particularly surprising.’ But for people like me, who don’t live in inner-city neighborhoods and are white, you look at that footage and you’re appalled.

We’re still in the early stage of a technological revolution, and it’s transformed what we get to experience outside of ourselves. That’s what’s made this moment possible.

“I can’t believe that the Supreme Court thought we didn’t need the continuing protection of the Voting Rights Act. It’s the greatest triumph of democracy of the 1960s. And it’s incomprehensible to me that we would, as a nation, retreat from that promise.” — Kevin Boyle

Is the Black Lives Matter campaign a continuation of the civil rights movement, a completely new moment in history or some combination of both?

The genesis of the Black Lives Matter movement is, obviously, police brutality. But I think it’s become something way bigger than that, which to me is really the most exciting and promising thing about this moment. There is a core issue that galvanizes people. For the Southern civil rights movement in 1950s and ’60s it was the integration of public space, it was voting rights, in the North it was the integration of schools or the equalization of schools or the integration of neighborhoods.

The Black Lives Matter movement is built on that core issue of police violence, but it’s blossomed out in all sorts of really fascinating and important ways, in much the same way the civil rights movement in the ’50s and ’60s did. It’s raised questions about all sorts of forms of inequality, including segregation and mass incarceration.

How is the Black Lives Matter campaign different from the civil rights movement?

Martin Luther King’s great contribution to the civil rights movement — and it’s not surprising because he was a theologian — is that he took the Christian story of redemption and put it right on top of the movement. He transformed it into a redemptive act: White America, particularly the white South, embraced the sin of racism. African Americans walked into the face of that sin. They confronted that sin. They took that sin on their shoulders. They suffered for that sin. They died for that sin. And by that act they redeemed the soul of America.

And that’s become iconic, the measure by which all other activism should be placed. Now you have the Black Lives Matter movement, which isn’t saying, ‘Oh I’m going to suffer for your sins.’ It’s saying, ‘You should solve your own sins, and stop imposing them on me.’ That’s a way harder lesson, and a lot of whites bridle at that. The Black Lives Matter movement is demanding that they give up something that they have, which is the power that comes with being white.

In Arc of Justice, you wrote, “Segregation had become so deeply entrenched in urban America it couldn’t be uprooted, no matter what the law said.” Is that statement still accurate?

So there’s an official measure of segregation that the U.S. Census Bureau does once every 10 years in metropolitan areas with more 500,000 people. It’s called the Index of Dissimilarity. That measure says on a scale of 0 to 100, what percentage of African Americans would have to move in order to make the entire metropolitan area actually integrated. If you get 100 on this scale, you are completely segregated. If you get zero, you are completely integrated.

According to the last measurement, in 2010, the most segregated metropolitan area in the country is Milwaukee. Eighty percent of African Americans in Milwaukee would have to move [to make the city completely integrated]. That’s one step away from apartheid!

So the level of segregation in the United States, physical separation in American metropolitan areas, is absolutely through the roof. And it’s all better than it was 10 years ago but not by a heck of a lot.

How do you break this cycle?

It’s a chicken and egg question. In the ’20s you had white people saying ‘Look, I don’t want black people living next to me.’ The thing is that, even in the ’20s, not all whites were that racist. But the forces of the marketplace came in, and realtors said ‘Look, if a black family wants to see a house in a white neighborhood, we won’t show it to them.’ Banks started to say, ‘If African Americans want to buy in a white neighborhood, we won’t loan to them.’ So you had this racism that some white people felt, and then you combined it with these forces of the marketplace and you institutionalized it.

I really believe that whites are much less racist than they used to be. But those forces of the marketplace still sit there, though most of them are illegal now. The challenge is to try to break those structures.

And then I get this question all the time. People say, ‘Yeah, but if you destroyed those structures, wouldn’t black people just want to live with other black people?’ And that’s a great question, and I suspect an awful lot of black people would want to do just that, which is a great American tradition.

When my family lived in Columbus [Ohio], we lived in a neighborhood that was 30 percent Jewish, which is really high. Why did Jewish people choose to live there? Because they have to walk to temple, because they want to be near their friends, they want to be near their family, they want kosher stores nearby. It’s a great American tradition. That’s not a big deal.

The difference is that if you’re Jewish in Columbus and don’t want to live in that neighborhood, nobody cares. You can go wherever you want. As long as people have free choice and then they want to cluster together, more power to them. But you have to break those structures if you want to give people the free choice, and that’s what we haven’t tackled.

The civil rights movement occurred two generations ago. Are we all that far removed from what we think of as history in terms of segregation and discrimination?

One of the things that history can do for people is give them a sense that the struggles against segregation and discrimination are all in the past. It’s painfully obvious that they’re not in the past. All you have to do to see the continuation of segregation, if you happen to be a Northwestern student, is take the Red Line from Howard down to its end point at 95th Street. You’ll watch segregation roll by you.

No, we are not as far removed from what we think of as the ancient past as we like to think. So when I was working on Arc of Justice, I went down to Dr. Ossian Sweet’s hometown in central Florida and spent the afternoon with his little brother, who was about 90. We were sitting in his living room, and I was asking him all these historical questions, and he was very politely putting up with me. Somewhere in the middle of that conversation I thought to myself, ‘This man I am talking to is the grandson of slaves.’ This was 2002 or 2003. All of a sudden this history that we think of as ancient, wasn’t. It was all compressed sitting in that man’s living room in Bartow, Fla.

How much do you think segregation played into the deaths of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray and other violent catastrophic events we’ve witnessed in recent months?

Ferguson is a classic example. Until 20 years ago it was a white suburb. Then African Americans started moving in, whites left, and it became a predominantly African American suburb, but the power structure remained white. So you had a white police force in a largely African American suburb, and all sorts of tensions arose from that.

It also became a poorer suburb. Property values are falling because neighborhoods are getting poorer. You can’t raise taxes because it’s not politically feasible. So what did they do in Ferguson? They created this system, which is not that unusual, sadly enough, in which you raise money through court fines. And you enforce that with a police department that’s white when people are black, and you accelerate this dynamic of tension, which leads to this tragedy. So the segregation of the neighborhood is fundamental to what happened there on that street that day.

In a perverse way, and I stress perverse, [the events that have led to the Black Lives Matter movement] have had a positive effect. Not what happened — God knows no one should have to die for us to have these conversations — but at least we’re having them in a way that we weren’t three or four or five years ago.

In June 2013 the Supreme Court nullified provisions of the Voting Rights Act that required jurisdictions with histories of discrimination to submit changes to voting laws for federal approval. What are the implications of the weakening of the Voting Rights Act?

In 1965 Lyndon Johnson went before Congress on national TV and made this extraordinary speech — it’s the best thing he did, the high point of his presidency — in which he said he was going to introduce legislation to secure the right to vote. And then he said, ‘It’s not just Negroes but all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of racism. And we shall overcome.’ What’s amazing about that moment is he didn’t say, ‘You shall overcome. They shall overcome.’ He said, ‘We shall overcome.’ Obviously, he was drawing on the sacred hymn of the movement, but in that moment he was also joining that movement.

That was such an American moment. It said voting rights, for God’s sake, are not something that belong to this group or that group. It’s a fundamental American right. I can’t believe that the Supreme Court thought we didn’t need the continuing protection of the Voting Rights Act. It’s the greatest triumph of democracy of the 1960s. And it’s incomprehensible to me that we would, as a nation, retreat from that promise.

Where do we, as a society, go from here?

One of the things people will say over and over again is that laws can’t change people’s hearts, and that’s absolutely right. Forget about changing people’s hearts. Change people’s actions. Make it so that the structures that sustain racial inequality in the United States get broken. You have to take the laws that are on the books that prohibit discrimination in the housing market and enforce them. You have to think of creative ways to encourage integration of neighborhoods. You have to think of ways to reform a justice system that unfairly falls overwhelmingly on African Americans and catastrophically on African American young men. You have to think about ways of creating an educational system that doesn’t define your opportunities simply by your ZIP code. And then you have to actually act on those things.

The great challenge in the United States, and it’s always been a great challenge, is that the promise of equality is written into the very founding documents of this country. So the question is, simply, how do you live up to it? You have to transform the institutional structures, the forces that create and sustain inequality. Do we have the political will to do that?

In early 2015 Kevin Boyle was named among the inaugural class of Andrew Carnegie Fellows. He also received a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar grant. He’ll use funds from both awards to support his research and writing during a sabbatical year in 2015–16, during which time he is working on an intensely intimate microhistory of political extremism and government repression in the early 20th century. Using a lifetime of personal letters, the book explores the radicalization of Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an Italian-born anarchist in the 1910s and ’20s. Boyle is also completing a book on the history of the 1960s.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email