|

Growing up in Turkey, Ozge Samanci was always drawing: in notebooks at home; on school papers; while sitting in a café with friends. But the assistant professor of radio/TV/film, now 40, was raised in an achievement-oriented culture that will sound familiar to many Northwestern students and alumni, urged by her parents to study hard so she’d get into good schools and land in a stable, lucrative career. Reluctant to disappoint her parents by veering off script, she couldn’t allow herself to think of art — her true passion — as anything more than a hobby.

Little did she know that those years of frustration and self-doubt would provide the fodder for Dare to Disappoint: Growing Up in Turkey (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), a well-reviewed graphic memoir that has significantly raised her profile within comic-book culture. Samanci’s teaching career is similarly focused on helping students find their own voice, by teaching them new ways to tell stories.

“My thinking is shaped by comics, but I never committed myself to a single art form,” Samanci says. “I’ve built an academic career on making and exploring images, and meanwhile I’ve kept drawing, like it was a second full-time job. I have an inability to dedicate myself to one thing, which is a blessing and a curse.”

A slight woman who could pass for a graduate student, Samanci is thoughtful, but not self-serious. The daughter of two teachers, she grew up in the coastal city of Izmir, at a time when Turkey was under the control of a military dictatorship. After graduating from college with a math degree, she scraped by on tutoring and drawing comics for a popular humor magazine before applying for a job in the department of visual communication and design at Istanbul Bilgi University. “I had no portfolio — only my comics — but they hired me,” she says. “I was supposed to be a teaching assistant, but the first year I was really the office boy. I did anything that was needed. Gradually they gave me teaching duties.”

However, the job did allow her to attend classes on full scholarship, a perk she soon took advantage of.

“The first time I sat in a film class,” she remembers, “I thought, ‘This is heaven.’ ” After completing her master’s degree in film and television, she began teaching but had little time or opportunity for research. So she decided to follow her many friends who were studying in the United States. “I was curious about the challenge of living in another culture,” she says.

She ended up at the digital media department at Georgia Tech, which she says was the perfect fit. “I used my background in mathematics to learn coding and started making installations that combined comics and digital media.” After a two-year fellowship in the art practice department at the University of California, Berkeley, she came to Northwestern in 2011.

“I wanted to stay in the United States, so I was a very passionate job applicant,” she says with a laugh. Samanci’s hiring was part of an overall push to bring the radio/TV/film curriculum in line with current technology. Thirty years ago, students were learning how to splice actual pieces of film; now they’re expected to edit images and sound digitally. “Ozge came into our department as the first and really only person working in new media forms,” says associate professor Eric Patrick. “She blended into the department seamlessly and built an entire curriculum in interactive arts, which has led to other hires in this area. With her presence, we began to think beyond static, single-channel screens.”

Samanci teaches courses that include Drawing for Media (merging analog drawings with digital images), Interactive Arts and, what’s become her signature class, Computer Code as an Expressive Medium.

“So many students are intimidated by coding, and this teaches them how to do it from scratch,” she says. “In all my classes, everyone has built something by the end of the quarter.” (Examples of student projects include a hologram dog that responds to whistles and a xylophone that makes abstract drawings with each note that’s played.)

“Ozge’s work is whimsical, political, artful and global in its perspective — a rare combination,” says professor David Tolchinsky, chair of the radio/TV/film department. “She also has a very special talent as a teacher, in her ability to draw art and science together. I’ve been at conferences where professors complain about teaching computer programming to artists, saying it can’t be done, or if it is done, it’s unpleasant for all involved. Ozge has magically found a way to do the impossible: Students are learning coding and liking it! We’re lucky to have her.”

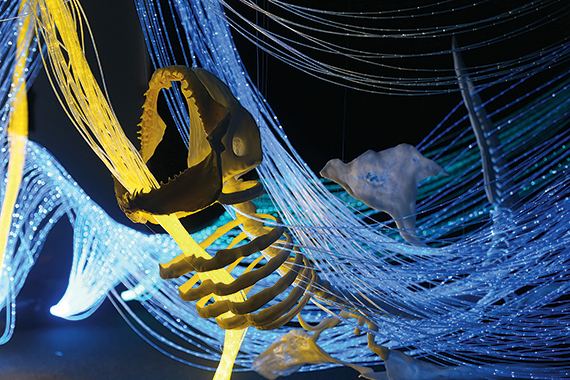

In addition to teaching, Samanci designs her own interactive projects, showing her work at worldwide events, such as the International Symposium on Electronic Arts and the Advances in Computer Entertainment conference. A recent installation, “Fiber Optic Ocean,” explored the intersection of nature and technology by bringing attention to the underwater cables that are invading sharks’ natural habitat. Samanci built reproductions of shark skeletons she’d studied at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, then wove fiber-optic cables through the bones. Lights and music were then incorporated using signals from live sharks tracked via GPS, as well as data that reflected the number of tweets being sent per second in real time. In Samanci’s words, it’s “a data-driven interactive installation that composes music.”

Ozge Samanci’s “Fiber Optic Ocean,” an installation that creates unique musical scores dependent on live data, conveys the consequences of technology’s invasion of oceans, such as its impact on sharks’ habitat.

Other interactive projects include “Plink Blink,” where viewers “compose” music by blinking their eyes, and “Personal Storm,” in which waves of water on a screen move according to how close a viewer is standing. (The quicker you move back and forth, the stormier the water.) Samanci is also interested in blurring the space between real life and comics; she, along with collaborators, has designed a motion-capture program that transforms a person’s movements into a drawn environment and a “GPS comic,” which changes according to the location of the reader/viewer.

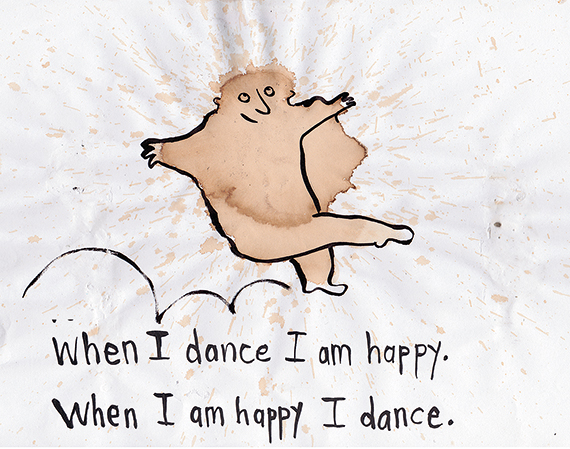

But Samanci still believes in the transformative power of pen and paper. Even as she was working her way up the academic ladder, she kept drawing comics. “My hand demanded the practice,” she says. In 2006 she began an online journal, “Ordinary Things,” posting a new image each day, based on something she’d seen or observed. That discipline allowed her to build and perfect her style.

Ozge Samanci shares her observations of the world in her online journal, “Ordinary Things.”

“I’ve always wanted to make a book, but I wanted it to have a unique aesthetic,” she says. “It’s not enough for the drawing to look professional — I wanted a publisher to see my work and say, ‘We have to have this!’”

Samanci’s images are a combination of line drawings (often more than one drawing overlapped in layers), watercolor and collage. Unlike most other comics, her work isn’t confined to rectangular or square frames; her pictures float in the white space of the page. “Memories blend into each other,” she says. “I don’t like trapping them in boxes.”

That approach gives her the freedom to make certain images larger than others as well as use words as artistic elements. But doing away with a rigid structure comes with its own pitfalls. “You have to make a clear path for the reader to follow,” she says. “If they don’t know where to look, they’ll drop the book immediately.” She says her mathematics training helped her figure out the right proportions between images, so it would be clear how the story progresses.

Publisher’s Weekly called Dare to Disappoint a story that “resounds with honesty and humor,” and a New York Times review noted, “For all its seriousness, the book never seems heavy. … Among [Samanci’s] talents is knowing how to make even a harsh story take flight.”

Seeing the book in print at last was the culmination of a long-held dream; Samanci had been thinking of telling her own story in graphic form for 15 years. “They didn’t publish that kind of thing in Turkey,” she says, “so I thought I had invented it!” Reading Marjane Satrapi’s influential graphic memoir Persepolis in graduate school was a revelation. “Its success really opened up a genre,” she says. “It showed people that one culture could be interested in another culture’s story, in a graphic novel form.”

Over the next few months, Samanci plans to start her next book, which will most likely be only semi-autobiographical; unlike her fellow cartoonists Alison Bechdel and Robert Crumb, she prefers to keep her personal life private. She’s also preparing for a busy travel schedule that includes both academic conferences and bookstore signings. “I’m living two full-time jobs in one body,” she says, laughing.

Happily, she has a means of escape when life gets stressful. “When I’m drawing, I go to a place in my mind where I almost stop thinking,” she says. “All my troubles disappear. It’s a place people reach in different ways — some people with meditation, some with sports. I reach it through art.”

Elizabeth Canning Blackwell ’90 is a freelance writer in Glenview, Ill.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.