Sex Matters

Watch the 60 Minutes feature on how pharmaceutical drugs can affect men and women differently and learn more about the lunchtime chat that sparked Melina Kibbe's interest in sex differences in basic science research.

Tell us what you think. E-mail comments or questions to the editors at letters@northwestern.edu.

Ever wonder about those strange designations we use throughout Northwestern to identify alumni of the various schools of the University? See the complete list.

Find Us on Social Media

More sex-specific basic science research could save lives.

One day during lunch, medical researcher Melina Kibbe shared with colleague Teresa Woodruff her promising findings on the use of nitric oxide to treat scar tissue that occurs after vascular surgery.

Woodruff asked one question: “Have you studied it in females?”

That query caught Kibbe off guard. She had studied the drug’s effect only in male rats. So, with encouragement from Woodruff and a grant from her Women’s Health Research Institute, Kibbe purchased female rats and reran the study. That was her eureka moment.

“I found very big differences in the way male and female animals reacted to the therapy,” Kibbe says. The use of nitric oxide to treat scar tissue worked in the males, but it did not initially work in the females. “I had to use a much higher dose in the females.

“That’s when I became a convert.”

Woodruff ’89 PhD, director of the Women’s Health Research Institute and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Kibbe ’03 GME, professor of surgical research, and neurobiology professor Catherine Woolley are among the Northwestern researchers spearheading an effort to address the underrepresentation of females in basic science research. They argue that researchers should focus on sex as an important variable in the earliest stages of basic science research.

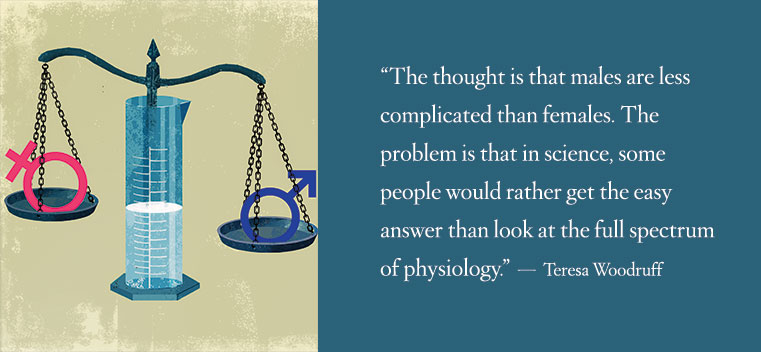

The long-accepted male bias — the National Institutes of Health only mandated that women and minorities be included in basic clinical studies in 1993 — stems from an old-school rationale among researchers that the natural hormonal cycle in females could affect study outcomes. “The thought is that males are less complicated than females,” Woodruff explains. “The problem is that in science, some people would rather get the easy answer than look at the full spectrum of physiology.”

Time and money play a role too, says Kibbe. A study with twice as many lab animals costs twice as much and takes twice as long.

But not accounting for sex differences at the preclinical level has costly consequences too: Eight out of the last 10 drugs that were pulled by the Food and Drug Administration were removed based on adverse effects in women, Woodruff says. In 2013 the FDA cut the recommended initial dosage for Ambien in half when it was proven that women metabolized the popular sleep drug more slowly than men. Now Ambien, known generically at Zolpidem, is labeled with different suggested doses for men and women.

“If you consider the big picture from basic research through translational research to clinical testing, it’s much more efficient to understand early whether there are differences between males and females than it is to find out later,” says Woolley, who studies the biology of the brain.

Kibbe recently reviewed the leading medical journals in her field to find out if other researchers were making the same mistake she had made. Out of more than 2,300 articles published in 2011 and 2012 on basic science research using animals, 22 percent of the publications did not specify the sex that the researchers had used. “That is atrocious,” Kibbe says. “Of the studies that did actually state the sex, only 3 percent had both males and females.”

She says that studying only males does a disservice to both sexes. “There could be a treatment that doesn’t seem to work in males, so it’s never pursued,” she says. “But it could be something that has tremendous benefits in females, and at a higher dose it may work in males, but we would never know.”

Kibbe is working with medical journal editors to require that researchers at least state the sex of the animals in their study, and if they use only one sex, they should explain why.

With such efforts, the conversation about the need for sex-specific research is gaining traction. Leslie Stahl profiled Kibbe and Woodruff on 60 Minutes in February. In March the WHRI Leadership Council wrote to Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, to encourage government support for sex-based research.

“We’re trying to shine a light on all of this,” says Woodruff. “The ultimate goal is to make sure every person has the right drug that’s right for his or her genetic makeup, and the first thing we have to do on our way to personalized medicine is to study males and females equally.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Email

Email